- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

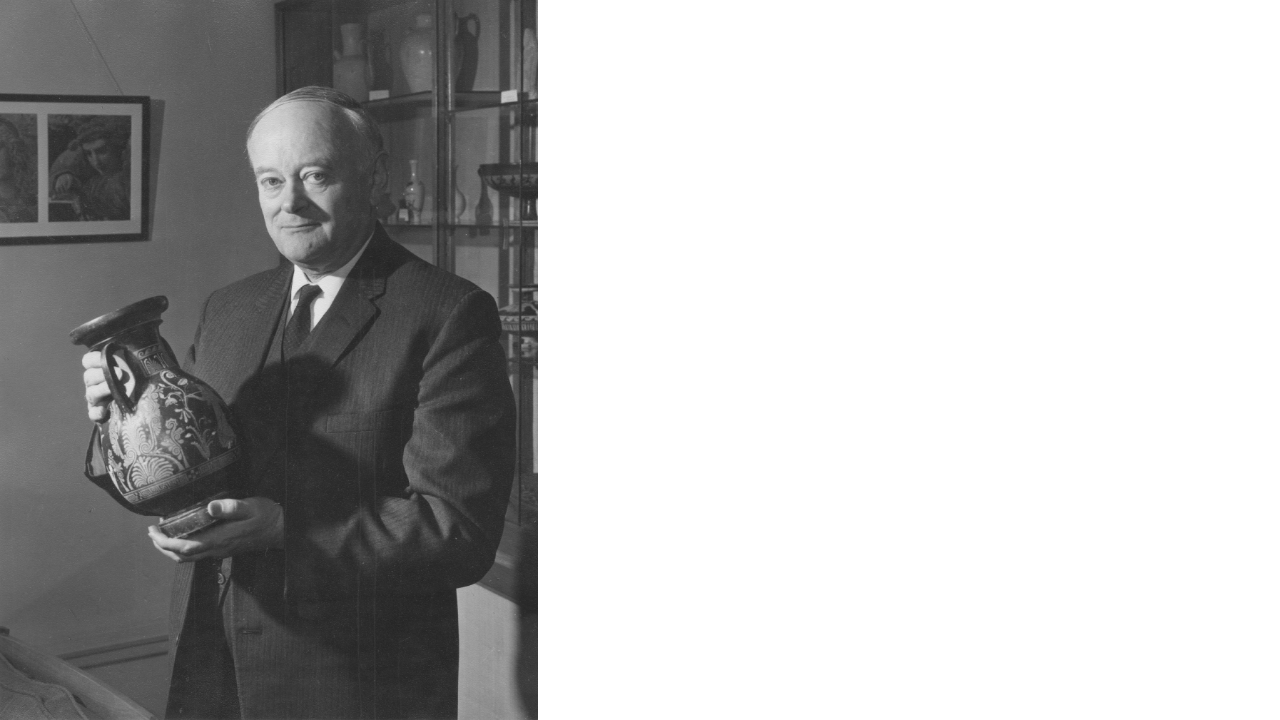

During the Second World War, the classical art historian Professor A.D. Trendell emerged as one of Australia’s most brilliant cryptographers. He combined the connoisseurship of ancient Greek vases with the art of wartime codebreaking to decipher Japanese messages, directly contributing to the Allies’ success in the Pacific theatre of war.

The art of the ancient world and the art of codebreaking do not obviously go together. Yet during the Second World War Professor A.D. Trendall, an expert in ancient Greek vase-painting, emerged as one of Australia’s most brilliant cryptographers. His academic work focused on what is more specifically known as South Italian vase-painting, the decorated pottery produced mainly in the 4th century BCE in Greek cities founded in South Italy and Sicily. His wartime work involved decoding Japanese messages, directly contributing to the Allies’ success in the Pacific theatre of war.

Who was Professor Trendall? Arthur Dale Trendall—always known as Dale—spent most of his life in Australia, but he was in fact a New Zealander, born in Auckland in 1909. At school, he excelled in maths and languages (including Latin) and went on to study classics at the University of New Zealand (Otago), where he was introduced to ancient Greek art. This became his lifetime interest.

In 1931, Trendall travelled to England to continue his classical studies at Trinity College at Cambridge University, where he was supervised by the renowned classicist A.S.F. Gow. This relationship did not get off to a good start: as Trendall left the room after their first meeting, he overheard Gow exclaim ‘another damned colonial!’. However, Gow soon realised Trendall’s intellectual abilities and interests, and it was through Gow that Trendall met the Oxford scholar J.D. Beazley, the expert on ancient Athenian vase-painting whose work very much inspired Trendall’s study of South Italian pottery.

Beazley’s work involved the attribution of ancient Athenian painted vases to specific artists. These vases—of which thousands still survive for us today—were not usually signed by their makers. Very occasionally they bear the name of the potter, or painter, or both, but such signatures are rarities.

Yet, despite the apparent anonymity of these ancient artists, Beazley was able to assign individual vases to particular hands. He seems to have used a version of the Morellian method, an approach developed by the 19th century art historian Giovanni Morelli in relation to Renaissance artworks, which likewise are often unsigned. Morelli’s method involved looking not simply at the overall style—because it is easy enough for one artist to imitate the general style of another—but at the small details, such as the way an artist depicts toes, or nostrils, or drapery folds. These details are often repeated little idiosyncrasies that effectively form the signature of a particular painter.

Beazley adapted this method and applied it very successfully to Athenian vases, making up names for the otherwise unknown artists based on favoured motifs (e.g., the ‘Painter of the Woolly Satyrs’) or modern connections such as the city or museum where a significant work was held (e.g., the ‘Berlin Painter’). Through this form of connoisseurship, a huge amount of artistic and archaeological evidence could be put into order, especially chronological order, and the imagery better used to understand ancient Greek culture and society.

Dale Trendall was intrigued by Beazley’s approach and further inspired by his first visit to Italy in 1932, including to the magnificent site of Paestum, which was one of the centres of production of South Italian pottery. At the time, South Italian pottery was not a fashionable subject of study: it was regarded as somewhat inferior, with provincial and imitative products that were second-rate in comparison to the works produced in Athens.

This meant that Trendall was able to be one of the pioneers in the field and, inspired by Beazley’s work, he published his first book, Paestan Pottery, in 1936. During his long career he produced further major publications identifying the wares and artists of four other main areas of production: Campania, Lucania and Apulia in South Italy, and Sicily.

A fragment from a Lucanian vase of c. 400 BCE in the Trendall Collection may be used to demonstrate Trendall’s method. It shows a scene of a well-known Greek myth, the ‘Centauromachy’, or battle between the Lapiths (a legendary tribe) and the centaurs, the half-human, half-horse creatures of mythology.

The forelegs of a rearing horse are clearly attached to a human torso, and a human elbow is visible at the top of the fragment, near the tail of another centaur. The Lapith warrior, his helmeted head and shield preserved, is about to plunge his spear into the centaur. Trendall attributed this fragment to an artist he called the ‘Palermo Painter’ because it displays the painted details typical of works by that specific hand, especially in the Lapith’s facial features: the fleshy lower lip and short upper one; the rounded chin; the upper eyelid lines which almost join; the distinct black pupil; and the shorter lower eye line.

Trendall had been awarded a fellowship at Trinity College in Cambridge but in 1939, just as the Second World War broke out, he moved to Australia to take up the position of Professor of Greek at Sydney University. His academic work was curtailed by the war, since he could no longer make the trips to European museums and sites essential to his study, but he still managed to be productive.

For example, in 1942 he published the first detailed study of the Shellal Mosaic, the 6th century CE mosaic uncovered by the ANZAC Mounted Division in Palestine in 1917 and currently in the Australian War Memorial. His friends and contacts overseas also helped him, especially in the purchase of new artefacts for Sydney University’s Nicholson Museum.

One such friend, Noël Oakeshott, would look out for ancient vases coming up for sale in London and acted for Trendall if he wished to buy them. In 1942, she acquired a krater (wine bowl) then attributed to the Dolon Painter (now to the Minniti Group) and also spotted a vase by Python, one of only two South Italian vase painters known to have signed their works. She thought Trendall would be interested in this vase also, and sent him a telegram which read:

DOLON DISPATCHED HAVE PYTHON TEN POUNDS

Trendall often recalled the summons to the Australian military censor to explain the quite obviously encoded contents of her message. It was, of course, a perfectly innocent communication, but if the military censors had anything of a classical education, they would have instantly recognised the name ‘Dolon’ and become even more suspicious.

In the ancient Greek myths of the Trojan War, Dolon is the Trojan solider who volunteers to spy on the Greek camp. Dolon was not a very good spy; he was immediately spotted by the Greek heroes Odysseus and Diomedes, who killed him as soon as he had revealed what the Trojans were up to. The ‘Dolon Painter’ takes his name from a South Italian vase that depicts this story. The scene shows a forest, with Dolon in the middle wearing the skins he hoped would act as camouflage, and on either side Odysseus and Diomedes are about to apprehend him.

The impact of the Second World War on Trendall’s work, however, went far beyond antiquities shopping and in fact called upon his very particular intellectual skills. In late 1939, the Chief of Naval Staff proposed that an Australian codebreaking organisation be established. As a result, in January 1940 a small group was formed in Sydney and asked to study Japanese signals traffic. The members included two Sydney University mathematicians, Professor T.G. Room and Mr R.J. Lyons, and they soon invited the newly arrived Dale Trendall to join them, who in turn brought in Mr A.P. Treweek, a lecturer in Greek. Of the four, Anasthasius Treweek was the only one who knew some Japanese and had a military rank (Major).

This group was highly skilled in mathematics and languages, disciplines extremely useful in codebreaking. Trendall was good at both, and especially the complexities of highly inflected languages such as ancient Greek and Latin, which require logic and a good understanding of the mechanics of languages. Indeed, Treweek later commented that Trendall naturally absorbed Japanese, despite never taking any lessons in it. Together they studied cryptography, mainly at weekends and in their spare time, and were provided with Japanese messages for practise.

Early in 1941, the group succeeded in breaking LA code, a relatively simple Japanese cipher used for low-level messages. They were given other sorts of messages to practise with. One was a letter in a dot code intercepted by the postal censorship, which turned out to be a quite explicit love letter written by an eminent British gentleman (with a knighthood) in China to a married woman in Melbourne. The Sydney academics proposed that the letter be sent on to its recipient but with ‘Careful!—The Censor’ inserted at the beginning in the same dot code. Whether or not the censors followed this advice is unknown.

Such was the success of this group of codebreakers that it prompted the creation of something more formal. Commander Eric Nave, an Australian naval officer who specialised in Japanese, had run a small intelligence unit at Victoria Barracks in Melbourne since early 1940. It seems to have been on Nave’s initiative that a new section devoted to breaking Japanese diplomatic codes was set up.

Room, Lyons and Treweek were called up for full-time duty in Melbourne and they moved there in the middle of 1941. Trendall remained in his post in Sydney but was available for part-time duty if required. The nature of the war was, of course, about to change very rapidly: on 7 December 1941 Pearl Harbour was attacked, Japan and the United States entered the war formally, and Australia found itself in a very different strategic position. As a result, on 12 January 1942, Dale Trendall reported for duty in Melbourne to Commander Nave.

Initially, the codebreakers worked at Victoria Barracks, but in March 1942, they moved to an apartment block called ‘Monterey’ near Albert Park Lake. Here, offices were created for Nave’s Special Intelligence Bureau (SIB) and it was also home to the American FRUMEL (Fleet Radio Unit Melbourne). Room, Lyons and Treweek continued to work directly under Nave, and later in 1942 were deployed in different directions. Trendall, however, was put in charge of the group breaking Japanese diplomatic codes, and over time he was joined by new recruits. In total, 33 staff were employed between January 1942 and the end of the war.

Two of this group warrant special mention because of their connection with Trendall. One was Ronald Bond, who at just 19 years old had graduated in classics with first class honours from Sydney University, where he had been taught by both Trendall and Treweek. He became Trendall’s deputy and headed the group after Trendall finally returned to Sydney in 1944.

The other was Arthur Cooper, a British consular officer who was an expert in Chinese and Icelandic. He arrived shortly after the move to Monterey in 1942, having been evacuated from Singapore. He had managed to smuggle his beloved pet gibbon Tertius into Australia—thus Tertius was, as Trendall commented, ‘a highly illegal gibbon’.

Cooper was recalled to Britain in December 1942, but he made a very positive impression on Trendall during his time in Melbourne. Trendall later recalled Cooper as ‘a really good linguist… for intelligence purposes he was very much at the top of the tree’. No doubt there is a gentle monkey joke in this assessment.

In 1942, four codes and two ciphers were used by the Japanese. All four codes could be read, and most traffic in the FUJI cipher. A main task was to ascertain the daily key for the FUJI cipher. According to Bond, Trendall devised a technique for determining this daily key and from there breaking the FUJI cipher. The messages were diplomatic; their value mainly related to economic warfare as up until the end of 1942 shipping information was sent in diplomatic codes.

One message the group decrypted must have been a particular source of satisfaction: it was an assurance from the Japanese ambassador in Budapest to his Foreign Ministry that it was highly unlikely that the Allies were reading his communications because Japanese was such a difficult language. This message was read loud and clear by Trendall and his codebreaking team in Melbourne.

Other messages, however, were the source of serious concern. One revealed that the Japanese were reading field communications between Australian guerilla troops in Timor. Admittedly, Australian ciphers at the time were not very complex, but it was a problem that had to be remedied and Trendall did just that. He invented a new cipher called, appropriately, TRENCODE. It was highly effective: simple enough to be used readily in the field, but sufficiently complex that it took hours or days to break it—by which time the information was redundant. Such was its success that TRENCODE was reportedly still used by the Australian military until at least 1946.

In late 1942, the Monterey team was moved back to Victoria Barracks and named D Special Section. Trendall returned to Sydney in March 1943 but was recalled in July; the Japanese were introducing new ciphers and his expertise was needed. One was called GEAM, the acronym of the Greater East Asian Ministry. GEAM was introduced on 21 July 1943; by 12 August Trendall had broken it, beating his rivals in London and Washington. Later attempts to reproduce the steps Trendall took to break GEAM were not entirely successful, and in fact Trendall himself could not really account for it: he simply said he had an inexplicable ability to see patterns in encoded text.

An ‘inexplicable ability’ must in large part be a natural ability, combined with rigorous training in relevant disciplines. Trendall certainly had both the natural ability and training in mathematics and languages needed for success in codebreaking. But did he have some extra talent?

A recent book on cryptographers in Australia during the Second World War notes that Trendall’s linguist skills were important for his war work but doubts that his renowned expertise in South Italian pottery would have been of any use in solving codes. Is that really the case? The connection is certainly not obvious, but Trendall’s success in attributing thousands of ancient vases to individual painters was based on his ability to detect significant patterns within a large amount of graphic information—precisely the work of a codebreaker. It was Trendall’s skill and experience in the connoisseurship of ancient art that made him a brilliant modern cryptographer.

In 1944, Trendall returned to Sydney University and resumed his career as a classical art historian. He moved to Canberra in 1954 to become the Master of University House and Deputy Vice-Chancellor at the Australian National University (ANU). On his retirement in 1969, he took up the position of Resident Fellow at the newly founded La Trobe University in Melbourne.

Following his death in 1995, his bequest to La Trobe University resulted in the establishment of the A.D. Trendall Research Centre for Ancient Mediterranean Studies, which continues to maintain Trendall’s legacy and promotes the study of ancient art and archaeology, especially through its superb library and Trendall’s research archive of some 40,000 photographs of South Italian vases.

To this day, Trendall’s scholarship dominates the study of South Italian vase painting and the archaeology of South Italy in the Classical period. However, his wartime work is much less well known, and indeed the man whom Commander Nave would later describe as ‘the best’ of the codebreakers was notoriously reticent about this period of his life.

Nevertheless, in 1990, Trendall agreed to an interview in which he was asked about the process of codebreaking. His musing on that question must surely also apply to his work in ancient vase attribution: ‘You get a feeling for it. Your eye lights upon something and … bang!’

In writing this article I am indebted to the following for information: Ian McPhee, close friend and colleague of Dale Trendall; RS Merrillees, ‘Professor A.D. Trendall and his band of classical cryptographers’, Strategic and Defence Studies Working Paper no. 355, 2001, Australian National University, Canberra; D Ball and K Tamura (eds), ‘Breaking Japanese Diplomatic Codes. David Sissons and D Special Section during the Second World War’, 2013, ANU Press, Canberra; C Collie, ‘Code Breakers’, 2017, Allen & Unwin, Sydney; and Corinne Fenton, author of ‘My Friend Tertius’, 2017, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, for generously sharing her research on Arthur Cooper.

The Shrine of Remembrance gratefully acknowledges the support of La Trobe University in the development of this article and associated programming.

Author:

Gillian Shepherd is Director of the A.D. Trendall Research Centre for Ancient Mediterranean Studies and Senior Lecturer in Classics and Ancient History at La Trobe University.

Enjoyed this article? You might be interested in:

- Art, Espionage and Professor A.D. Trendall A special lecture that recorded at the Shrine of Remembrance by Big Ideas ABC Radio National in partnership with La Trobe University's Trendall Research Centre.

- Discover more stories from the Second World War here.

Updated