- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

- Services:

- Army, Air Force, Navy, Nursing services

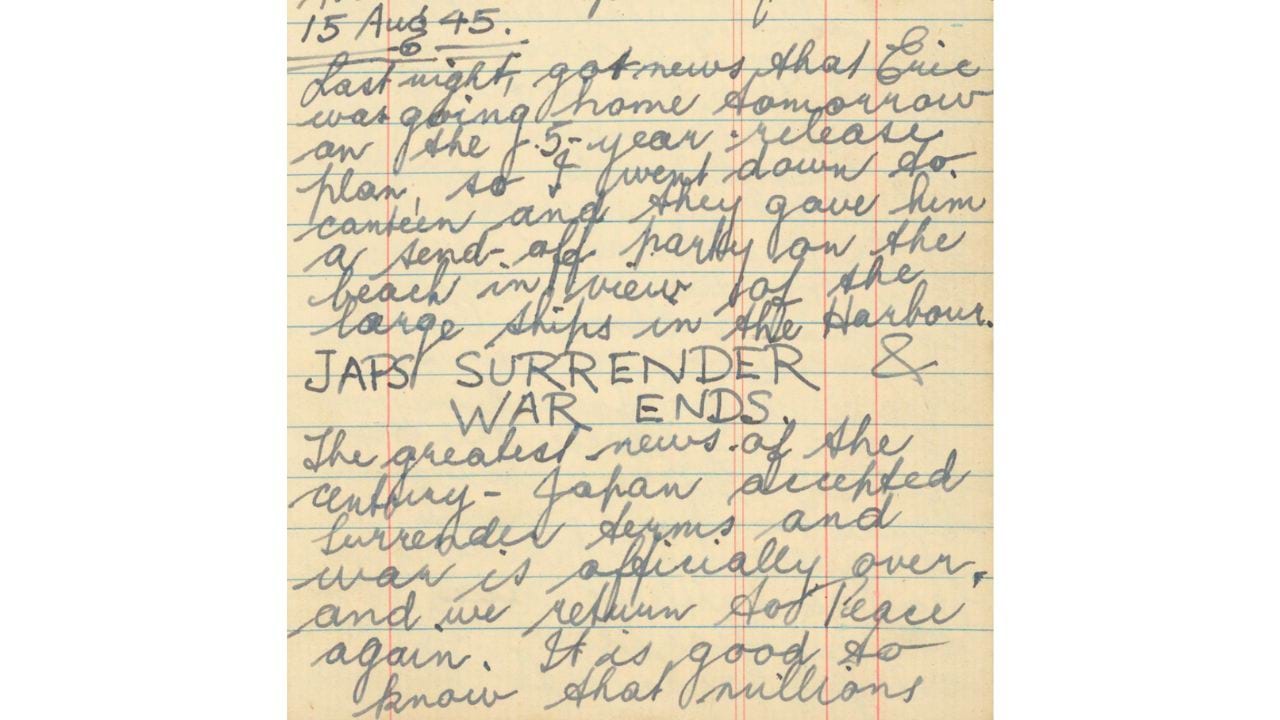

On 15 August 1945, a soldier serving at Bougainville wrote: “JAPS SURRENDER AND WAR ENDS. The greatest news of the century”. People poured into the streets in Australia’s major cities, embracing each other. Children had the day off school. But in Nagasaki, Australians did not have the luxury of hope. In Johore, Australians were on the brink of starvation.

The culmination of the Second World War in the Australian memory is usually incarnated by the jubilation and partying in city streets. This was described in a letter received by seaman Pete Russell Mayor in Tokyo from his sweetheart Greta; “People went really mad; they threw anything in the line of papers out of the windows and in a short while the streets were carpeted with paper. “It was inches deep in Collins Street”. Scenes of the “Dancing Man” filmed in the streets of Melbourne typify the understanding of the Second World War’s ending, like the confetti pouring down from the heavens, signalling an outpouring of emotions among a moment of deliverance.

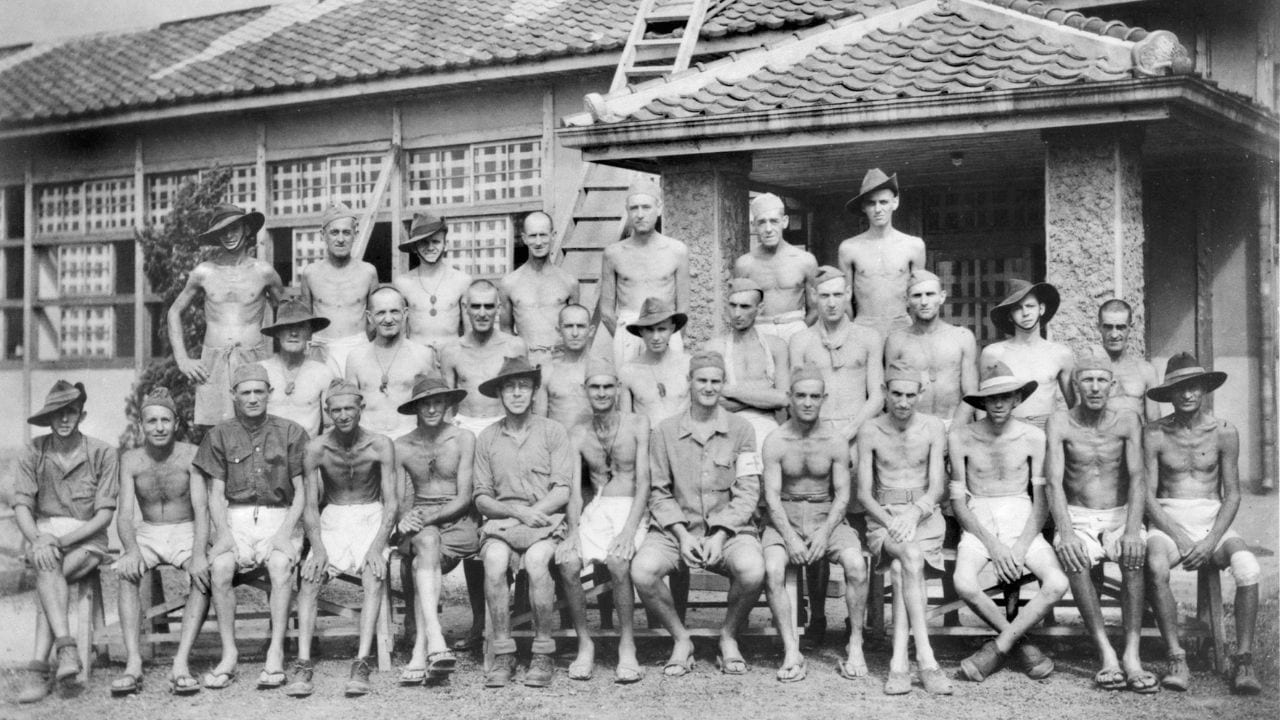

Yet thousands of kilometres away, a very different ending to the war was unfolding – one that did not simply end on 15 August 1945. While some celebrated, many grieved, and all breathed a collective sigh of relief, those closest to the location of the war itself – especially among prisoners of the war around the Pacific – experienced a far more complex conclusion. When their deliverance finally came, their relief was muted, starvation persisted, forced labour continued for many, and most were simply left to fend for themselves.

Those on Johore, the southern state of what was then known as Malaya, had been so deprived of food that their daily meal involved a stew of tapioca and roots foraged from nearby ground. When Red Cross parcels fell from the heavens bringing freedom, they weren’t to know that the worst thing to treat starvation is an abundance of food. “Our eyes are bigger than our bellies and one poor chap last night ate a pint of sugar and died during the night,” Stan Arneil, a prisoner of war in Johore, wrote in his diary. This was emblematic of the circumstances that defined the end of the Second World War for those closest to its point of crescendo, not of the home front, nor the front line, but a different human experience altogether.

V.P. Day, 15 August 1945, was the day of the Japanese surrender. 18 days later, the Pacific War officially ended aboard the U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay amid General Macarthur’s contrived official surrender, in which the Japanese were seen to yield to the Allies. In the meantime, Japanese forces were conceding in piecemeal fragments. Piecemeal concessions also occurred within Japanese prisoner of war camps, especially those closer to, or on, the Japanese mainland. In the Fukuoka prisoner of war camp near Nagasaki, it still took three days for confirmation of the surrender. On 17 August, a surge of relief and rising optimism reached a volatile peak as emotions boiled over into physical altercations among the men, as recounted by Jack Nevell, a prisoner of war in Fukuoka, Japan, who kept a diary throughout his containment.

The war must surely be over. Excitement everywhere. Four fights this morning. They are becoming almost international contests. Dutch against the Australians. Aussies are well ahead.

The men were tense, at the end of their tether, and often bore visible scars that reminded them of their captivity. They soon began celebrations in earnest, mirroring the celebrations on the front in the Pacific, and those back home. They held a concert, with flags displayed prominently and national anthems bellowing. The Japanese camp commandant gave a speech telling them that all would be well. Two weeks later, on 1 September, the Dutch contingent in Fukuoka held a lively celebration for Queen Wilhelmina, complete with patriotic speeches. As Nevell wrote, “The Aussies soon had enough of it and eventually one, in a loud voice, said ‘F*** old Wilhelmina’, and a Dutchman hit him and then it was on. They are still repairing the damage”. Clearly, the end of the war had not dissolved the strain or hardened facades forged in captivity.

Some in other places in the Pacific did celebrate as B-29’s flew overhead. Tom Henling Wade, a POW in Tokyo, recalled: “prisoners waved, cheered, and skipped with pleasure among the fallen and bouncing boxes. It made glorious, theatrical spectacle”. Others, like Dorothy Jenner, a civilian internee in Japan, processed their liberation with a profound deepness of emotion. “Instead of cheering and screaming, the emotions were so deep that they dumbfounded us and we were completely silent”. Many could hardly ignore the devastation that surrounded them. “Two-thirds of the population of Nagasaki are dead”, Sister Regina McKenna, freed from internment in Nagasaki, wrote to a friend.

In Johore, days after the news had finally reached them, each man fell silent when presented with a pen and paper to write letters home on 6 September. It had only been on 28 August that leaflets dropped over the jail the Australians had now made their camp, telling them that the war was officially over and they would be going home. In the ensuing 24 hours, more men died from collapsed nerves, their strength finally giving out after prolonged strain.

Former prisoners of war could hardly leave camp and find a ship home; they were forced to remain among those who had held them captive during the war. In most cases, nobody even knew where these people were. A group of nurses who’d been taken from Rabaul and held on the Japanese mainland remained isolated in their camp for two weeks until, one day, three of them went into town and waved down an American officer, bringing him to camp. Jean McLellan’s 31 August diary entry simply read: “Eventful day – most of my life – we were FOUND!!”

The relief, and the complex and layered emotions visible in their deliverance, are entirely understandable given the hardships they were forced to endure. Stan Arneil, who kept a diary during his internment before and at Johore, wrote of his regimented prison life, working all day, “chasing time all the while”. Rations were irregular and unreliable; in April 1945 a working man was sustained daily on 400 grams of rice and corn. Any perceived slight against their captors or the honour of Imperial Japan would see even those rations sliced and the axe come down, as Arneil recorded, “with a vengeance”. By June, men like Stan Arneil were rejoicing at the prospect of half an ounce of chillies each, and reality was sinking in: “We repeat to each other, of course, day in and day out that the war must end and we all agree on that, but as we have been repeating the same things for three years we are not getting very far”. Optimism was at a premium when only two men out of twenty were deemed fit enough to work. By August, men were “scrounging” tapioca from the rubbish of Imperial Japanese Army quarters. “It is frightful of course to think that men have been reduced to such a state but still even the pigs at a local piggery eat much better tapioca and greens than we”, Arneil recalled.

On the Japanese mainland, prisoners were regularly beaten not only by their captors, but by members of the Japanese navy looking to take out some frustration. Men who stepped out of line could have their skulls split with their work tools by a Japanese guard. At Hainan, the prisoners had dug a pit between the huts where they were to be shot and dumped in the event of an Allied landing. By 15 August, 130 out of 273 Australians who had been shipped to Hainan had survived, and only eight were strong enough to bury their dead. Then, there was the Sandakan Death March, in which 980 prisoners were forcibly marched through hundreds of kilometres of mountainous jungle and marshland from Ranau to Labuan. Six prisoners escaped, and they became Sandakan’s only survivors. The rest were either left to die on the trail or exterminated upon arrival.

Some POW’s went in different, more ambitious, directions. Jack Nevell said:

Some of the lads have just landed back from robbing a bank. They have rice bags full of money. They had been drinking all the morning. When that started to pall, they decided they would go rob a bank to see if that would give them a kick.

Why rob a bank? Because the war was over, and nobody had come to fetch them. Because their existence as prisoners of war revolved around a strictly implemented routine, which had entirely disappeared. Because nobody had prepared these men to run their own camps, and, chiefly, because they were bored. In the words of one of their comrades in camp, the men were “feeling their way gingerly along and finding they can get away with nearly anything”. Jack Nevell himself, recording the exploits in his diary, was less enthused; “I am afraid I have not the stomach for the way a minority of the lads are carrying on, especially regarding the civilian population. I just want to get home and forget about it all”.

It is clear that for many, the war certainly didn’t end on 15 August. However, the Nagasaki bank heist did not go unnoticed. Fukuoka’s Japanese mayor rode his bike down to the liberated camp, demanding compensation, and every former POW was called to parade. The mayor gave a speech: “I quite understand these happenings. When the men were under the Japanese control, they were knocked about and treated badly. Now it is our turn to be knocked down and kicked. We expect it. There are no hard feelings”. He drew up a bill for 3000 yen, which was passed around the men. By the time it had reached its end point, the men had contributed 6000 yen. Everyone had satisfaction. Except the mayor had to walk home – “one of the lads had stolen his bicycle”.

Author:

Alessandro (Alex) Barilaro is a PhD student at Deakin University with an interest in historical narratives and dynamics, particularly those which emanated from Australian forces during the First World War. He completed the Australian War Memorial’s Summer Scholarship program in 2025.

Interested in other Second World War content? Click here.

Updated