- Conflict:

- Vietnam War (1962-73)

- Services:

- Army, Navy, Nursing services

1966 was the most important year in the Australian involvement in the Vietnam War. It would see large increases in the size of the force and set in place the manner in which the Australian Defence Force would operate for the next six years.

1966 was a seminal year in the history of Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Decisions taken during the year set in place the shape and scale of the Australian military contribution for the next six years. These political and military decisions markedly increased the size of our military commitment to the Vietnam War and eventually led to widespread political unrest on the home front. The stories in this article, of four young Australian men and women far from home, provide us with insights into one of the most important conflicts in our history. 1966 was the pivotal year in Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War, and as 2026 marks 60 years since those events occurred, it is timely to revisit the period.

Errol Wayne Noack

“I don’t want to go to war, but I must obey the call to duty. I will go and do my best.”

One of the most controversial aspects of the Australian commitment to the Vietnam War was the issue of conscription, otherwise known as national service. Introduced by the Australian government in November 1964, it required that all 20-year-old Australian men register for national service. Between 1965 and 1972, 15,300 national servicemen (nashos) were conscripted into the Australian Army, with 200 of them killed in action and 1,200 wounded in Vietnam.

While support for the commitment to Vietnam remained relatively high, the issue of conscription became increasingly unpopular, especially once young conscripts became casualties (they were old enough to be sent overseas to fight, kill and possibly die, but were too young to vote).

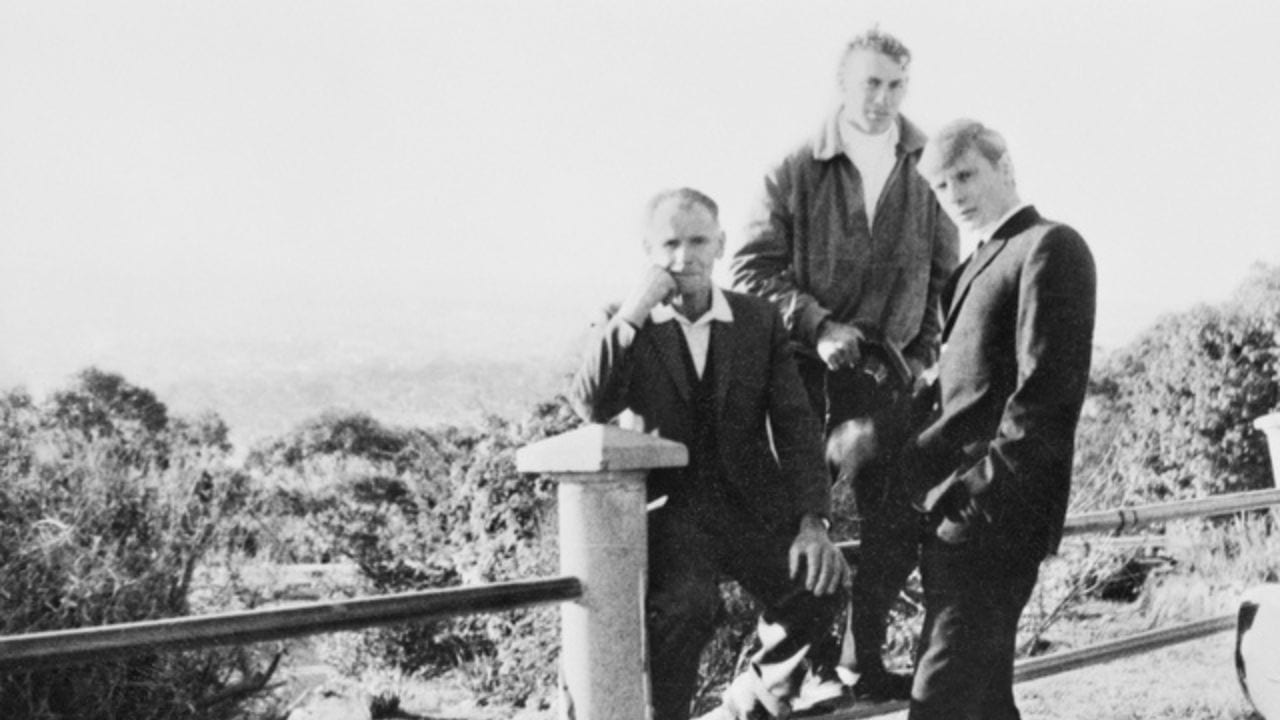

The first ‘nasho’ killed in action was Adelaide-born Errol Wayne Noack. He was in the first intake of national servicemen on 30 June 1965, joining the 5th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (5RAR) at Holsworthy, NSW. This battalion was the first to contain both regular soldiers and the newly inducted national servicemen. The unit had only three months’ notice that they were to deploy to Vietnam, but they prepared as best they could in this brief period, including training at the Jungle Warfare Training Centre, Canungra in the Gold Coast hinterland.

On 12 May 1966 Errol Noack left Australia, and within two weeks found himself on patrol in the area outside the 1st Australian Task Force Base at Nui Dat. The task of 5RAR was to clear the area around the base of People’s Liberation Force (PLF) soldiers – usually known as Viet Cong (VC), short for Vietnamese Communist. On 24 May, a firefight broke out and Noack was hit. Evacuated by the ubiquitous UH-1 ‘Huey’ helicopters, he died on the way to hospital. Tragically it was later discovered that Noack’s ‘B’ Company had been involved in a friendly fire incident with ‘A’ Company.

On 1 June, only weeks after saying goodbye to his family, he was buried in Adelaide’s Centennial Park cemetery. His death became a symbol for the fledgling anti-Vietnam War movement. Although the protests and marches that became a regular occurrence on television did not occur until the years between 1969-71, Noack’s death continued to be a touchstone for those opposed to the war. His death also bought about a change in government policy after his grieving father, Walter, who had just lost his only child, insisted that his son’s body be returned to Australia for burial. Prior to this, Australian service personnel killed on operations were buried in the closest Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery—in this case that was Terendak, Malaysia. Walter Noack forcefully argued that as the government was responsible for the death of his son, they could pay to return his body. Since 1966 it has been standard practice that the families’ wishes be acceded to, and bodies are now automatically returned to Australia.

Dave Sabben MG

“Gordon Sharp radios in that he’s facing at least a platoon of VC. He counts at least three MGs firing at him. Harry Smith tells him to withdraw towards company…Gordon radios in again, telling Harry that the VC are moving on both flanks, and that the platoon can’t withdraw without taking more casualties in the crossfire.”

The above passage was taken from letters written by Lieutenant Dave Sabben MG to his wife at home in Gosford, NSW. At the time, he was 12 Platoon Commander, D Company, 6th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR), during the most well-known engagement that the Australian Army was involved in during the Vietnam War–the Battle of Long Tan. Today, the date of that battle, 18 August, is known as Vietnam Veterans’ Day–the day we commemorate all those who served in the Vietnam War.

Dave Sabben was born in Suva, Fiji in 1945, but attended boarding school in Sydney from 1958 to 1962. Sabben volunteered for the army and then applied for officer training. After attending the first course at the Scheyville National Service Officer Training Unit, 55 kilometres west of Sydney, Sabben was posted to 6RAR in January 1966. The battalion marched through the streets of Brisbane on 31 May in a farewell parade, before boarding aircraft bound for South Vietnam in early June.

Just over two months later, on the night of 16/17 August, the Task Force Base at Nui Dat came under heavy mortar and recoilless rifle fire. The next day B Company was ordered to try and locate the enemy firing positions. They did this, and on 18 August D Company took over from them. Soon after 3:30pm on 18 August, contact was made by 11 Platoon. Led by another young National Service Lieutenant, Gordon Sharp, the platoon would take the brunt of the casualties on this day. But soon the whole company was engaged, as they found themselves surrounded and greatly outnumbered.

In torrential monsoon rain they fought desperately, as their perimeter shrunk and wave after wave of Viet Cong soldiers charged towards them under the cover of heavy machine gun and rocket propelled grenade fire. Artillery support from 161 Battery, Royal New Zealand Artillery, two Australian field batteries, as well as a US Army heavy battery was called in. At times they were firing ‘danger close’, with the shells landing less than 100 metres from D Company. Air support was also critical, with two Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) helicopters of No. 9 Squadron flying a resupply mission at treetop level to drop ammunition to the beleaguered infantrymen. Heavy ground fire was directed at the helicopters, but despite taking multiple hits they successfully completed the supply drop. The ammunition was rapidly distributed to the men, most of who were down to their last magazine. Despite the resupply, it was clear that D Company needed more support.

B Company were ordered to assist, while at the same time 3 Troop, 1st Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) Squadron with the men of A Company aboard also charged to the rescue. Four long hours after the battle had begun, they arrived, hitting the VC as they formed up once again to attack the survivors of D Company. The Battle of Long Tan was over, with the wounded evacuated by RAAF Huey helicopters. The next day, 6RAR swept the battlefield, finding two wounded Australians and the bodies of 245 VC and dozens of rifles, machine-guns, mortars and rocket launchers. While Long Tan would never be forgotten, 6RAR would participate in many more operations before their tour of duty was at an end in mid-1967.

Dorothy Angell

Dearest Mum & Dad, well, here I am back from the first day’s work; tired, filthy but happy. The work is really cut out for us here, but even though today was a bit of a shambles I think everyone is really going to work well together.

This passage is taken from the first letter that 26-year-old nurse Dorothy Angell wrote home to her parents. Working at Melbourne’s Alfred Hospital, Dorothy and other Alfred staff responded to a call from the South Vietnamese government to provide medical assistance for the civil population. As the war had escalated over the early 1960s, most civilian doctors were conscripted into the army, leaving fewer than 100 doctors to provide medical care for the entire South Vietnamese population. In response to that call for help, from 1964 until 1972, teams of doctors, surgeons, radiographers, anaesthetists and nurses from the Royal Melbourne and Alfred Hospitals were despatched.

The first team from the Royal Melbourne Hospital arrived in 1964 and were based in the Mekong Delta town of Long Xuyen. Conditions were rudimentary, with incredibly overcrowded wards, hundreds of patients in corridors and hallways, appallingly unsanitary conditions and a range of diseases and wounds that the Australians had never faced. Soon the Australian contribution increased, and Dorothy arrived in late 1966 at the newly established hospital at Bien Hoa, 25 kilometres from the capital Saigon. Bien Hoa was also home to the massive US Long Binh airbase, which meant frequent Viet Cong attacks, some of which endangered the hospital.

Medical assistance was provided to anyone, civilian or military, and as a consequence the hospitals were regularly overwhelmed with patients, meaning that shifts were very long and time off was infrequent. Supplies were intermittent or unobtainable and the nurses had to beg, borrow, re-purpose and re-use items to keep the hospitals running.

By the time the program came to an end in late 1972, more than 450 Australian doctors and nurses had served in civilian hospitals in Vietnam. They had treated more than 100,000 patients. While their posting to Vietnam had been incredibly difficult, most found it very rewarding. But like Australian military veterans, the civilian medical teams experienced post-traumatic stress and increased levels of cancer. Although it is still contested, the widespread use of pesticides and herbicides in Vietnam is believed by many veterans to be linked to the ongoing health problems of those who served in Vietnam.

John O’Callaghan

“Took the army up from Sydney to drop them off at Vung Tau”.

John O’Callaghan grew up in Gippsland, before enlisting in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) as a 16-year old in 1961. After training at HMAS Cerberus on the Mornington Peninsula, he was posted to the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne. Serving in the RAN for the next ten years, he deployed on vessels that supported operations in Vietnam on several occasions. The first of these occurred when the Melbourne escorted the Vung Tau ferry, the aircraft carrier HMAS Sydney, on her early trips to Vietnam in 1964-65. The RAN’s role was critical in supporting the Australian deployment to Vietnam—both for the Australian Army and the RAAF. Across 25 trips between 1964 and 1972, more than 16,000 army and RAAF personnel were carried to and from Vietnam, along with a multitude of equipment, weapons, vehicles and supplies. Without this RAN support the Australian war in Vietnam could not have occurred.

The government decided that the size of our commitment needed to increase in 1966. This decision meant that when O’Callaghan was posted to the new guided missile HMAS Hobart in late 1966, he would be off to Vietnam again. The Hobart became the first Australian combat ship assigned to the gunline—sailing up and down the coast of Vietnam to provide naval gunfire support to army operations onshore. Naval deployments to support operations in the Vietnam War were for six months duration, so in late 1967 O’Callaghan returned to Australia. He undertook more training before he returned to Hobart, serving on her during her 1970 deployment to Vietnam. Two years after his final tour to Vietnam, he left the navy in 1972.

These stories, among many others, reflect how 1966 was arguably the most important year in Australia’s decade long involvement in the Vietnam War. On 29 June 1966, during his official visit to the White House in Washington DC for a meeting with US President Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ), Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt had enthusiastically told reporters that Australia would go ‘All the way with LBJ’. This unequivocal statement was soon followed by the despatch of another infantry battalion and a squadron of tanks, as well as a RAAF bomber squadron.

As the size of the Australian contribution grew, and the numbers of national servicemen deployed increased, so too did the disquiet at home. While it would not be until 1970 that the moratorium movement saw 100,000 anti-war demonstrators take to the streets of Melbourne, the decisions taken in 1966 paved the way for that to happen. And finally, when Australians gather on 18 August to remember all those who served in the Vietnam War, it is 1966 and the seminal Battle of Long Tan that they recall.

Author

Dr Adrian Threlfall is a military historian who has worked at the Shrine of Remembrance for 14 years. In the past he was a history lecturer at Victoria University and La Trobe University. His next book, on the Australian Army in the Cold War will be released in 2026.

Enjoyed this article? You might be interested in:

- Our Vietnam War resources

- Vietnam Veterans' Day Commemoration

Updated