- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

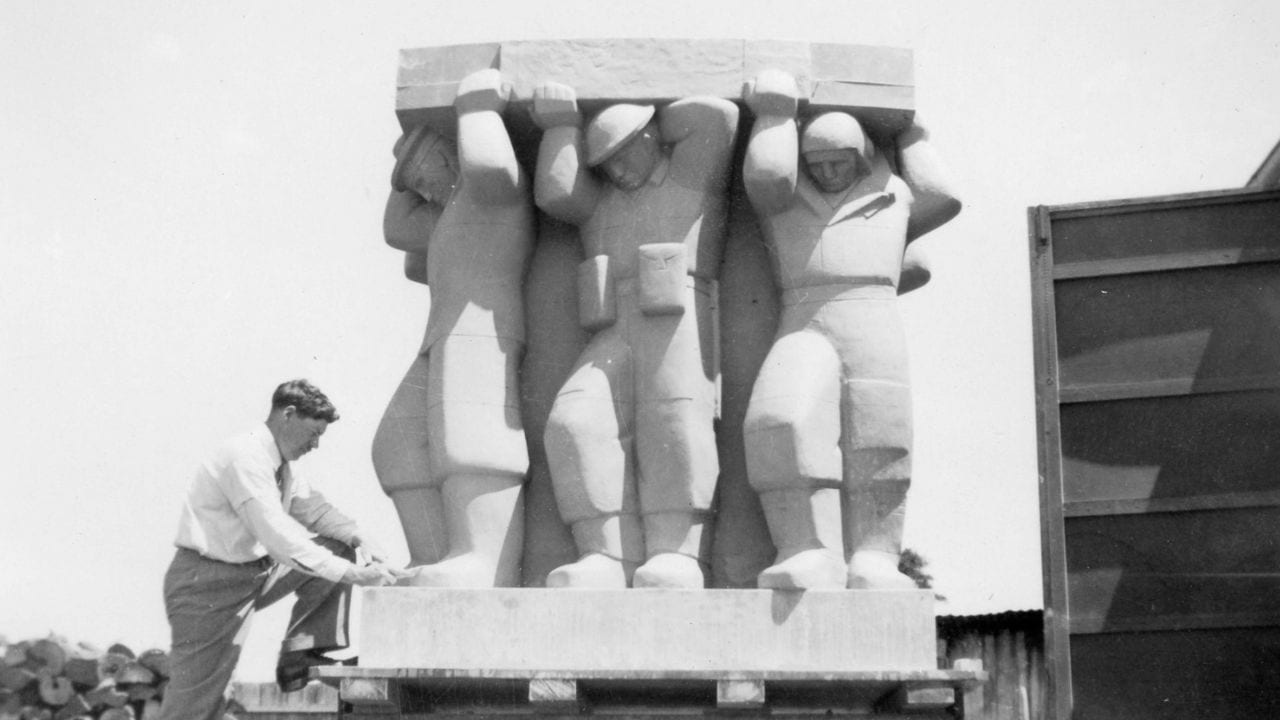

A group of young schoolchildren cluster around the Eternal Flame on the Shrine of Remembrance’s Forecourt. Gripping the metal railing with their small hands, they lean in to try to feel the warmth, then swing backwards, tipping their heads as far as they will go, craning necks to see the sculpture on top of the neighbouring cenotaph, trying to determine what the massive figures carry. It’s a scene that has repeated over the seven decades since its completion.

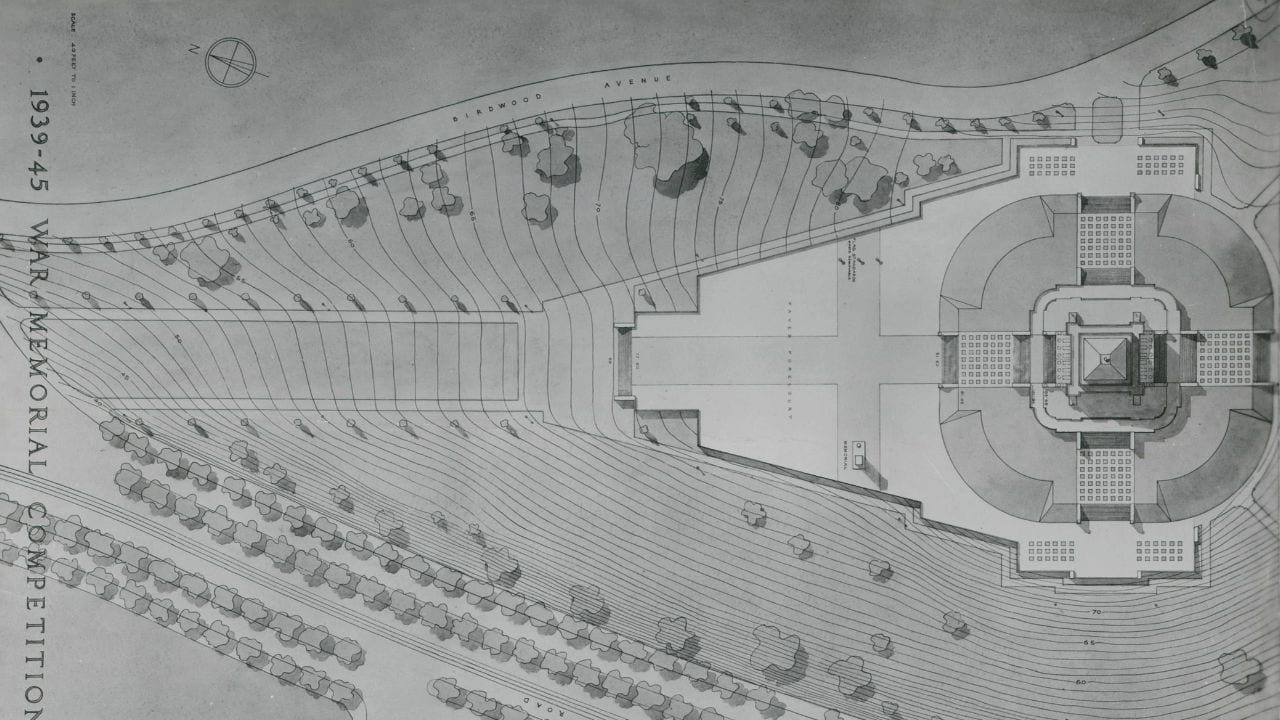

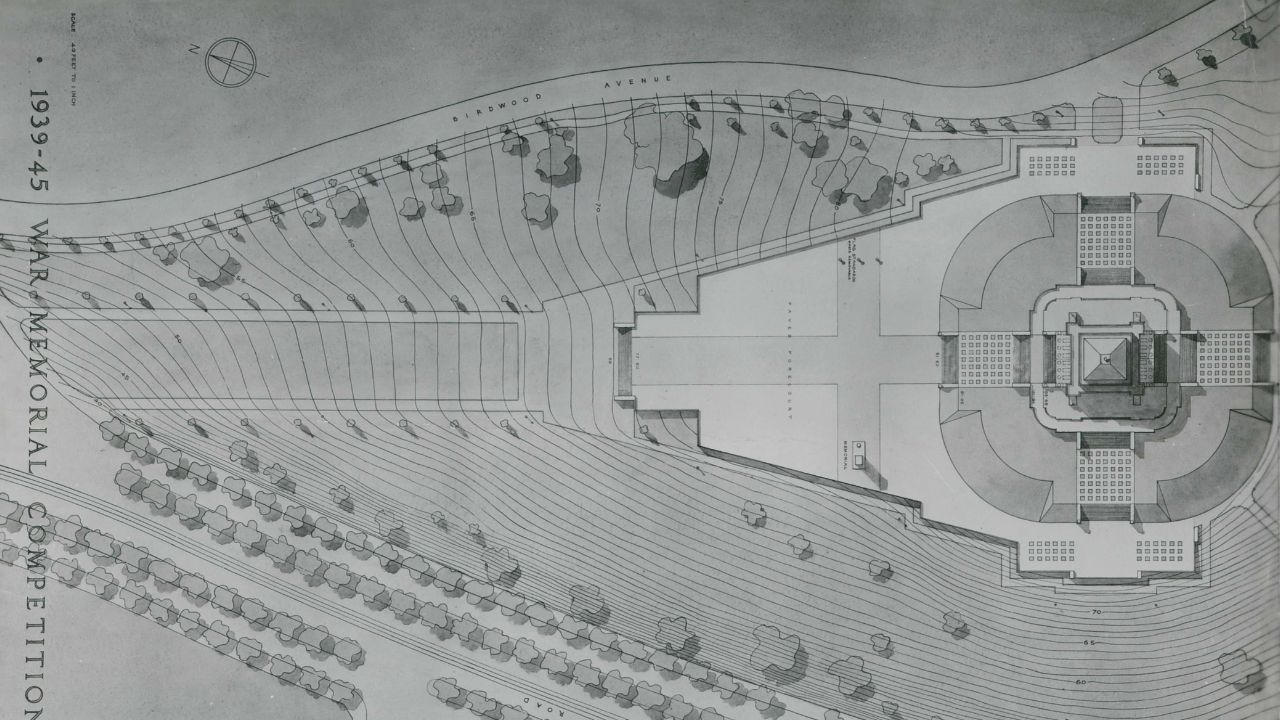

Viewed from the air, the forecourt extends seamlessly from the Shrine’s imposing geometry. Its cross-shaped, grass-bordered paving is terrain well-travelled by successive generations of visitors: veterans marching on Anzac Days; pilgrims approaching for more private remembrance; and tourists, dog walkers and schoolchildren. Many of us will remember performing a similar set of movements, and the feel of the railing on tiny hands. An older generation would also remember the reflection pool in the foreground of the Shrine, or the grass around the Shrine disturbed by a series of zigzagging slit trenches dug in 1942 to provide protection for staff at Victoria Barracks in the event of an air-raid at the height of the Second World War.

The Shrine itself was built to commemorate the service and sacrifice of Victorians in the First World War, fulfilling the community’s need for public remembrance and private grief. When the Second World War came to an end, the question of memorialisation again arose. How could the service of Victorians in this larger, and geographically closer, conflict be commemorated without detracting from the imposing and evocative memorial already occupying the site? To find a solution, in 1947 the Shrine Trustees held the first part of what would become a three-phase competition: a thesis competition, open to Australian veterans of either war, calling for suggestions.

Architects Ernest Milston and Alec S. Hall were declared joint winners, having independently proposed a great forecourt on the north side of the Shrine: a sensitive augmentation of the existing monument which would provide for large gatherings. Their visions would come to underpin the second phase—a formal design competition held in 1949 for which 21 entries were received.

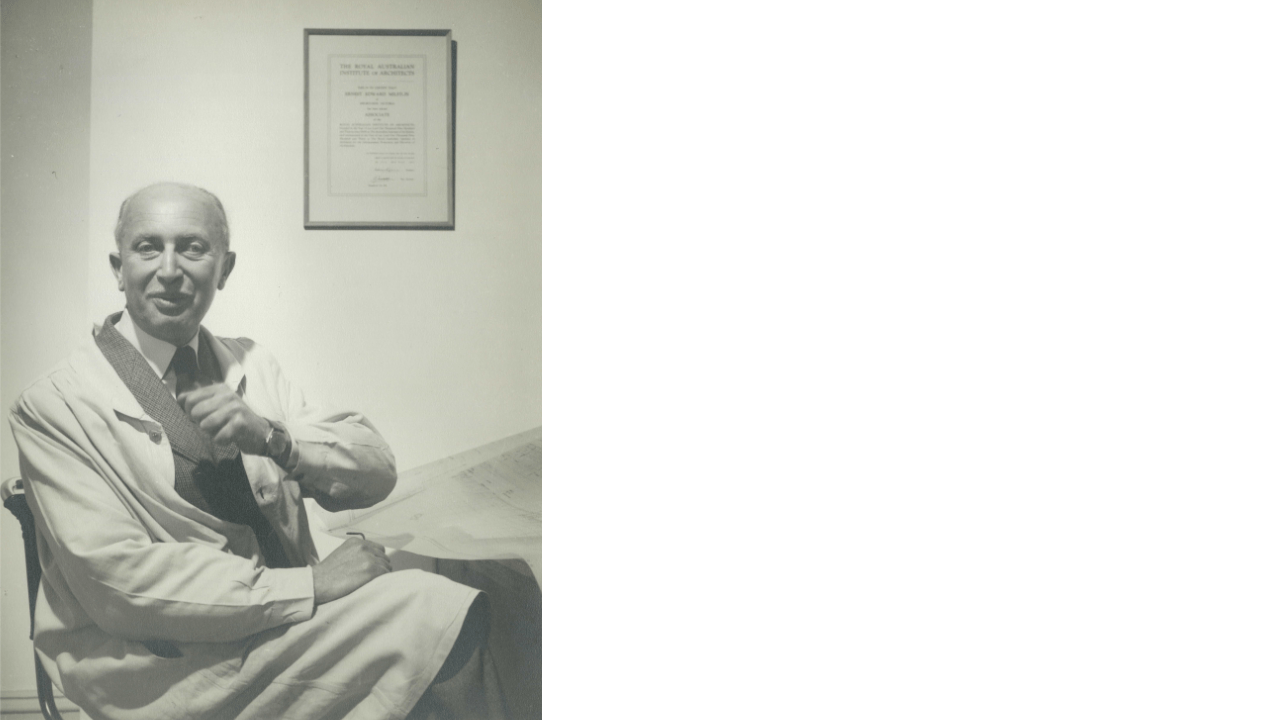

This was assessed by architects Robert Demaine, Marcus Martin and W. Balcombe Griffiths. Again, Milston and Hall emerged victorious: Milston secured first place and Hall second. The assessors and winners were all veterans from either the First or Second World Wars—or both. Yet Milston’s experience of war had an added element of tragedy.

Ernest Edward Milston (1893–1968) was born Arnost Edward Mühlstein to a Jewish family in Prague, Bohemia. His training as an architect at the University of Prague and the Academy of Fine Arts had been interrupted when he was drafted into the Austrian Army in 1918. Post-war, his career prospered in the newly formed liberal democracy of Czechoslovakia. Over the next two decades, he built a successful practice with Victor Furth in Prague. He travelled widely and mingled within intellectually brilliant circles that included figures such as writer Franz Kafka, portraitist Lotte Frumi, and architect Adolf Loos.

All this ended, however, with the outbreak of the Second World War and the German invasion of Czechoslovakia. As Jews, Milston and his family faced the full horrors of the Holocaust. Milston escaped for Italy in 1939, but the stark tragedy of his family’s eventual fate was revealed in letters from the Red Cross and the Council of Jewish Communities in Bohemia and Moravia in 1946, held in the Milston Papers at the University of Melbourne Archives. These carefully preserved typed sheets convey the terrible intelligence that his brother Viktor was deported from the Terezin ghetto to Auschwitz. No trace of his sister, or her family, could be found.

His family, business and homeland shattered, Milston arrived in Adelaide in 1940 to take up a job with the prominent South Australian architectural firm Lawson and Cheesman. He was one of several European architects seeking refuge in the tumultuous years either side of the war, bringing with them a wealth of knowledge, culture and experience that would have a profound impact on the Australian architectural profession.

Milston’s winning design was deceptively simple, comprising a trapezoidal paved and low-walled forecourt including a darker-paved Cross of Sacrifice, and punctuated by flagpoles, an eternal flame and starkly rendered cenotaph surmounted by sculpture. The assessors recommended that the paving around the cross form, and inside the trapezoidal boundary walls, be replaced with grass, as it is today. The sacrificial and religious symbolism of the cross is obvious, rooted in Christian symbolism, and echoed in the uniform use of the Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission’s Cross of Remembrance.

Its orientation echoes the internal and external cross-axial nature of the Shrine itself and provides distinct zones for the Eternal Flame, Cenotaph and flagpoles, while facilitating procession between these features. Viewed from the air, the cross is immediately recognisable, with Milston at one point describing it as an ‘open-air Cathedral’. But his initial thesis and the contemporary press coverage reveal an added inspiration—one drawn from ancient precedent, just as Philip Hudson and James Wardrop had done in their own design for the Shrine of Remembrance.

In 1942, Milston enlisted in the Royal Australian Engineers as a friendly (non-enemy) alien, serving within Australia. In his new country, Milston later wrote, he had hoped to find the freedoms that had characterised his homeland of Czechoslovakia between the wars; he was now ‘proud and happy to have thus been associated with the Australian Army and its great traditions’. He was naturalised in 1946 and anglicised his name to Ernest Edward Milston. Within three years, he had won both the thesis and architectural competitions.

In his thesis, Milston wrote of the potential to turn the existing Shrine site into ‘an architectural group’ akin to the Athenian Acropolis. In particular, he referenced the Parthenon and the long-destroyed, massive sculpture of Athena Promachos, which had been erected nearby.

Recognising the Shrine’s architectural importance and sacred character, he proposed that an adjacent large-scale sculpture—initially conceived as a winged victory ‘transporting to God a dying man who fell in battle’—sited to the side of a ‘large formal square’ for gatherings would be an ideal solution. Furthermore, a tracing in the Milston Papers depicts visually the analogy he sought to make, juxtaposing his proposed plan with a simplified one of the Acropolis.

The trapezoidal shape of the Forecourt echoes the Acropolis’s angled contour, while the tapering towards the northernmost point is reminiscent of the narrowing of the Acropolis towards its entrance gateway. The sculpture is prominent but placed carefully to the side to preserve the axial views of the Shrine itself. His vision underpinned his subsequent design for the second competition, but with the addition of the cross-shaped paving, the Eternal Flame, and the flagpoles. By that stage his thinking on the sculpture had moved on.

The third and final phase of the competition for the selection of a sculptor was held in 1951. It stipulated the size of the piece as well as its form: that of two servicemen from each service, carrying a dead comrade on a bier, to be mounted on a tall, stern-sided pillar. It was won by George Allen, whose design brought the massive form to life with a fitting solemnity.

Milston’s sympathetic solution to a design problem respected the original scheme, harnessing and enhancing Hudson and Wardrop’s classical allusion, but it also established a careful approach to additions on the Shrine Reserve, which carries through to the present day.

As generations of veterans, tourists and schoolchildren continue to visit, the various components of the ‘architectural group’ of the Shrine site may be added to, but the core commemorative elements, once introduced, have intellectual, spiritual and even tactile resonance. Just look at the schoolchildren, seven decades on, clutching the railing, leaning in, then gazing up.

With thanks to the University of Melbourne Archives, architectural historian Catherine Townsend and Dr Laura Carroll.

Author:

Dr Katti Williams is a Research Fellow in Australian architectural history at the University of Melbourne. She is an authority on commemorative architecture and soldier architects.

Enjoyed this article? You might be interested in:

- Previous shrine exhibition Designing Remembrance

- Learn more about the Second World War Memorial Forecourt

Updated