- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

The Shrine of Remembrance’s latest special exhibition, Eucalypts of Hodogaya, tells the story of a team of Australian and Japanese architects and landscape gardeners who created a masterpiece of memorial landscape architecture recognised by experts as one of the finest war cemeteries in the world.

Nestled within the hinoki pine and sakura cherry-shrouded hillscape of Hodogaya, five kilometres west of the Yokohama city centre, lies CWGC Yokohama—the Commonwealth War Grave Commission’s sole cemetery in Japan. The remains of 1,555 Commonwealth service personnel lie here, within a breathtakingly beautiful setting of 27 acres.

Most of the individuals buried and memorialised here perished as prisoners of war held in Japan and China during the Second World War (1939–45). Others succumbed to illness, disease or misfortune while serving as occupation troops between 1945 and 1952 or died in Japan as a result of illness, or wounds sustained during the Korean War (1950–53).

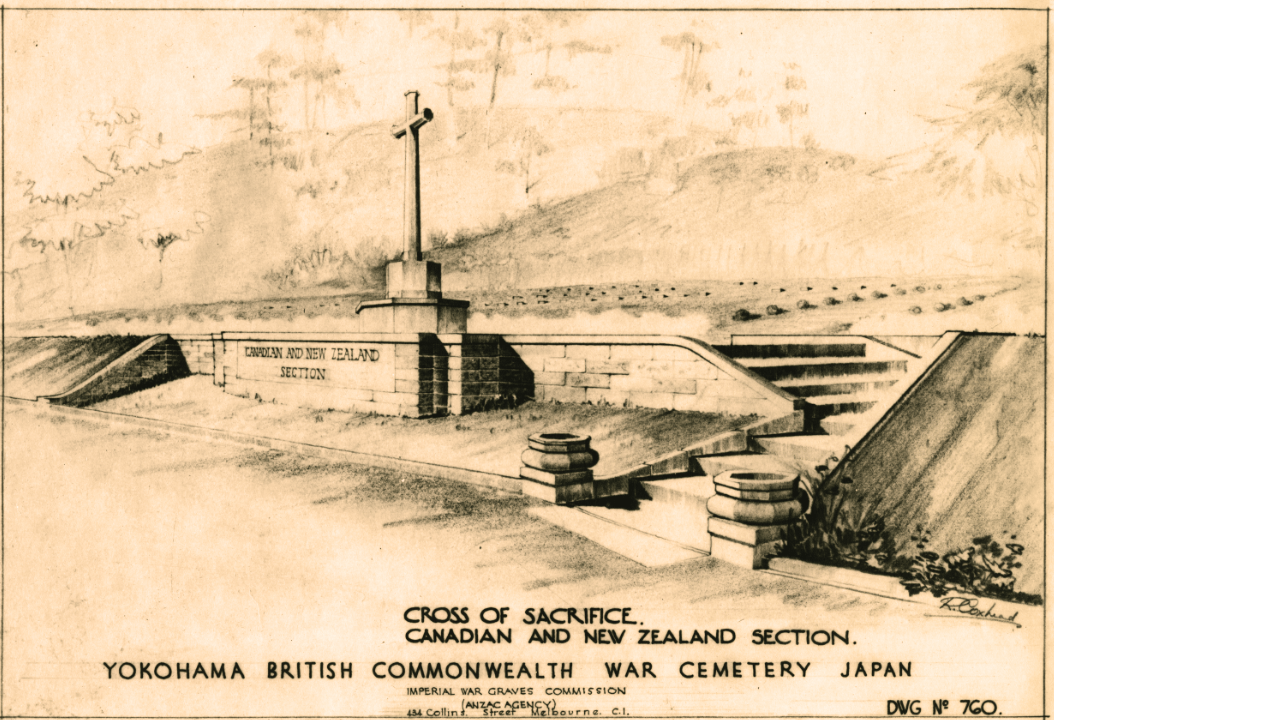

The cemetery itself is set into the natural landscape of Hodogaya, which changes dramatically with the seasons. Paths meander over CWGC Yokohama’s undulating hills and link five discrete burial grounds—a British section, an Australian, a joint New Zealand–Canadian, one section for the troops of pre-partition India, and the post-war section.

The Yokohama Cremation Memorial is located within the British section. It houses the ashes of 335 people whose names—save for 51 unidentified—are inscribed on the shrine’s walls. The Australian section, the second largest at Hodogaya after the British, contains 281 graves of which three are unidentified. It includes 10 sailors, 250 soldiers, eight airmen and nine merchant seamen. A further 57 Australians lie in the post-war cemetery.

This beautiful cemetery did not just come into being but was the result of vision and skilled workmanship. It was born of many careful and deliberate decisions made by a group of Australian and Japanese architects, who put aside recent wartime enmity to build an eternal memorial. Its design stresses the profundity of loss, the regenerative power of nature, the gratitude of a Commonwealth, and the reconciliation between nations.

Hodogaya

When United States Supreme Commander General Douglas MacArthur arrived in Japan in August 1945 at the head of a multinational occupation force, Yokohama—then a city of approximately 400,000—lay in ruins. The victorious Allies had much to do and high on their list of tasks was the recovery and burial of those Allied combatants who had died in Japan as prisoners of war (POWs).

Within weeks the Americans had established many temporary burial grounds across Japan, including one at the sports fields of the Yokohama Country and Athletic Club at Hodogaya. Following the American lead, the Australian War Graves Service (AWGS) also began consolidating Commonwealth war dead at Hodogaya. These burials were intended to buy time, until money and expertise became available to provide the Commonwealth’s war dead with the magnificent cemeteries they deserved.

The headquarters of the Australian-led British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) was at this time located not at Tokyo, or Yokohama, but Kure—in Hiroshima Prefecture—some further 800km west. The commander of BCOF, Lieutenant-General Horace Robertson, nevertheless selected Hodogaya, where the Commonwealth war dead had already been concentrated, as the site for the permanent Commonwealth War Cemetery on 4 July 1946.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The construction and maintenance of war cemeteries for all the nations of the British Empire had, since the First World War (1914–18), been the responsibility of the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC)—established by Royal Charter on 21 May 1917. Hundreds of cemeteries had been built across the world, many at locations of great significance to Australia, including at Gallipoli and the Western Front.

At the close of the Second World War (1939–45) Britain was victorious, once again, but thoroughly exhausted. Diminishment on the world stage and forced to contend with the growing nationalism and confidence of its Commonwealth partners, Britain could not—and would no longer—shoulder the burden of burying the Empire’s war dead alone.

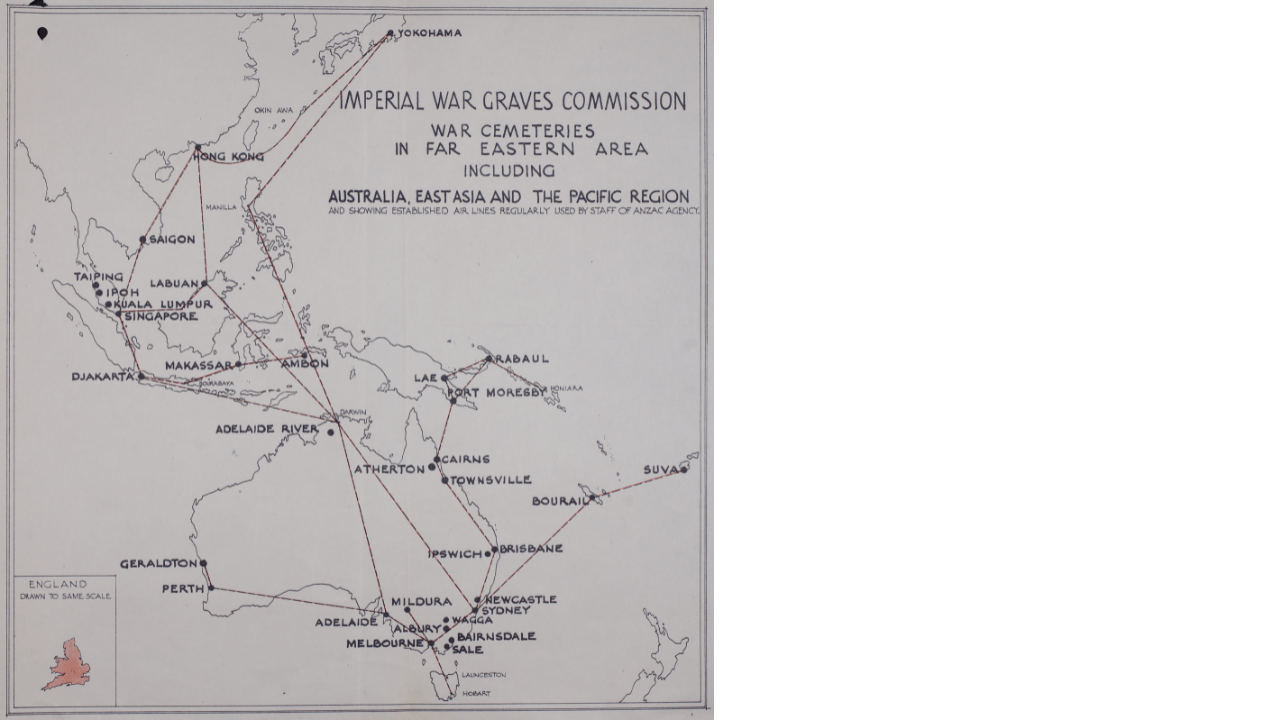

From June 1946 onwards, the IWGC was aided in its work by a new Melbourne-based organisation—the Anzac Agency—today known as the Office of Australian War Graves. The IWGC would itself be renamed the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) in 1960.

The Anzac Agency

In 1946, Brigadier Athol Earle Brown (1905–87), a former head of the AWGS, was appointed Secretary-General of the new Anzac Agency. Brigadier Brown quickly assembled a team of demobilised architects, engineers and horticulturists and established a headquarters in Melbourne.

The new Agency immediately began work expanding upon and creating new war cemeteries across Australia. Among these were the two most significant war cemeteries in Victoria—CWGC Springvale in Melbourne and the German Military Cemetery at Tatura.

Overseas, the Agency would be assigned responsibility for the design and construction of CWGC cemeteries at Labuan in Malaysia; Bomana, Lae and Rabaul in Papua New Guinea; Makassar in Indonesia; and Bourail in New Caledonia.

Maintaining IWGC standards across the Asia-Pacific was often very difficult. Local labourers, unused to such stringent construction methods, required close supervision. Suitable building materials often proved difficult to source. Civil strife in post-war, newly independent Indonesia made building cemeteries in that nation especially difficult. CWGC Makassar, in Sulawesi, was eventually abandoned and, in 1961, the graves were relocated to the nearby, British-built, CWGC Ambon.

However, at Hodogaya, the Anzac Agency was able to create a masterpiece, tapping into a skilled local workforce with a rich tradition of garden design. Between 1946 and 1951, the Australian architects forged fruitful partnerships with expert Japanese architects and suppliers to a degree not possible elsewhere.

One of Brigadier Brown’s early hires would be instrumental in the success of the Anzac Agency. Horace John Brett Finney (1913–97), the Agency’s Chief Architect from October 1946 until September 1949, was the chief liaison between the Agency architects, the AWGS, and the officials and contractors in all the countries where the new cemeteries were built. In Australia and across the Pacific, talented Anzac Agency architects, such as Alan Gerard Robertson (1908–2005) and Clayton Vize (1912–96), took the lead in the construction of beautiful cemeteries in New Guinea, New Caledonia and elsewhere.

Robert Coxhead (1915–87), meanwhile, took a primary design role at CWGC Yokohama. He was a keen photographer and artist and the exhibition features many keepsakes from his career. Among these is a pencil drawing of the Nikkō Tōshō-gū Shrine, in central Honshu’s Tochigi Prefecture, which Coxhead drew while touring a nearby quarry.

The build at Hodogaya was overseen by site supervisor Jack Leemon (1910–1962). He arrived in Japan with his family in 1948 and stayed until the cemetery was complete in 1951. Leemon, like Brigadier Brown, was a former member of the AWGS. At war’s end Leemon had travelled the entire length of the Thai-Burma Railway, recovering the bodies of the fallen. A year before that, Brigadier Brown had dispatched Leeman to Cowra, NSW, with the grisly task of identifying and burying the 234 desperate Japanese POWs who had died during the infamous camp breakout of August 1944. In 1964 a war cemetery, for all Japanese who died in Australia during the war, was established by the Anzac Agency at the same burial ground Leemon established.

Local Knowledge

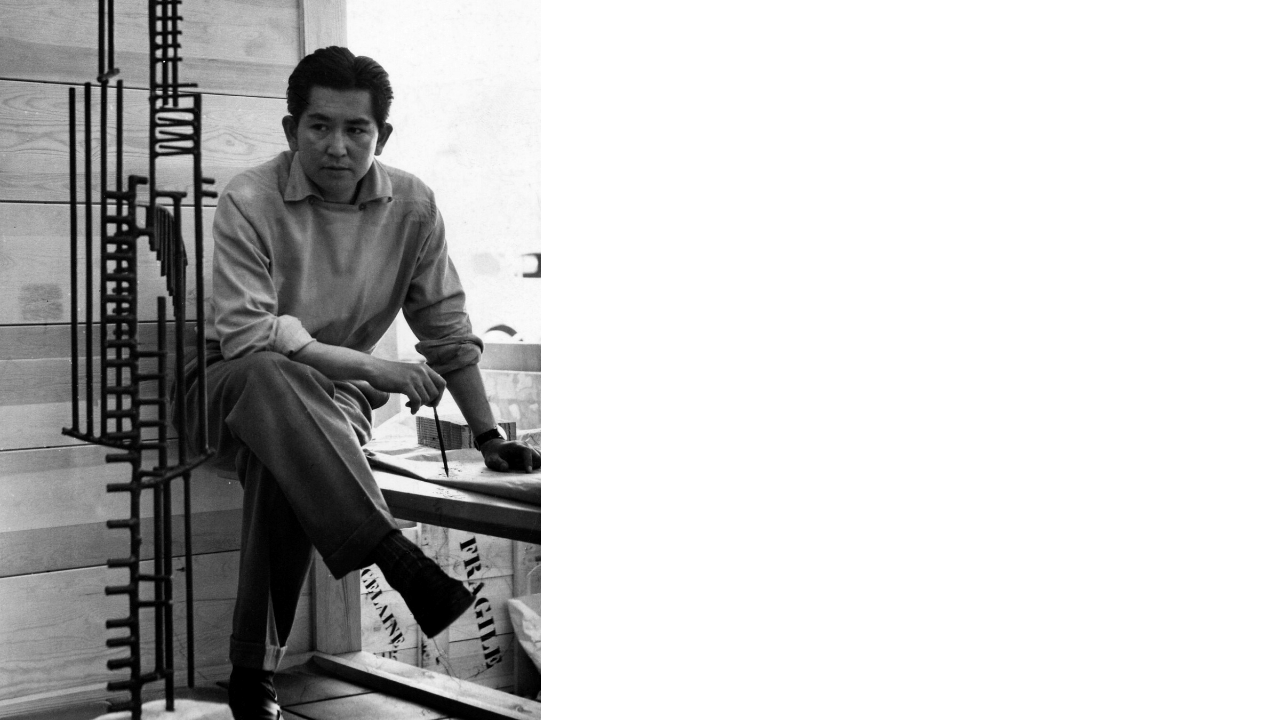

Peter Elliston Spier (1909–74), the Agency’s Director of Works, oversaw the Agency’s many complex projects across the Pacific. He was an admirer of Japanese culture and the exhibition features a selection of the many items he collected during his frequent trips to the country. It was Spier who was responsible for hiring two Japanese architects who would have a profound influence on the work done at CWGC Yokohama—Michael Yoshio Iwanaga (1912–2005) and Yoji Kasajima (1921–2012).

Michael Iwanaga was working for the American Embassy’s Foreign Buildings Operation Attaché when he was introduced to Spier by the American Christian missionary Paul Ruschin in 1946. Born in Fukuoka Prefecture but raised in the United States, Iwanaga studied architecture at the University of Washington under modernist Lionel Pries. He received an American Institute of Architects’ School Medal in 1937, before returning to Japan where he designed St Andrews Chapel at Kiyosato for Rusch. He was forcibly conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Army during the war and served in Manchuria, Malaya and Burma.

Yoji Kasajima was an architecture student at Nihon University during the war. After graduation in September 1945, Kasajima taught architecture at Jiyu Gakuen—a Christian school designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959). Impressed by Wright’s innovative use of the native Ōya stone, Kasajima was primarily responsible for the extensive use of the stone at CWGC Yokohama—most famously in its boundary walls. Indeed, it was while visiting the Ōya quarry (on advice from Kasajima) that CWGC Yokohama’s architect, Robert Coxhead, drew his picture of the Nikkō Tōshō-gū Shrine.

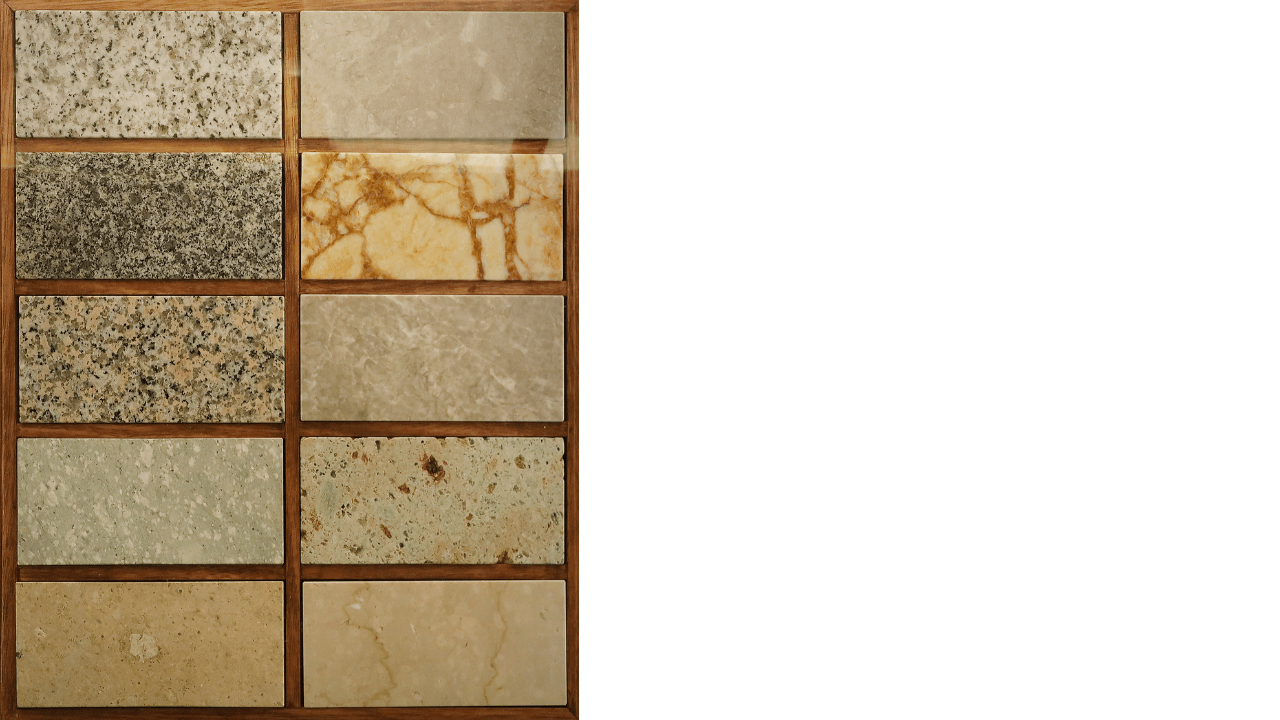

Ōya is a soft, easy to carve volcanic stone traditionally used to line Shinto burial chambers. CWGC Yokohama is, in fact, unique among CWGC cemeteries, both in terms of the large variety of stone used and its very specific uses.

The traditional religion of Japan, Shinto, seeks to establish and maintain harmony between divine nature spirits called kami (神). Everything in nature, living and non-living alike, is imbued with kami, and these spirits possess positive and negative characteristics. The Shinto worldview therefore lends a religious dimension to decisions that might not otherwise seem relevant including, for example, the building materials one might choose when constructing a sacred site such as a war cemetery.

Iwanaga and Kasajima were both Christian but were nonetheless steeped in these ancient traditions. Their approach to the design of the buildings at Hodogaya and the materials in which it was rendered had a profound influence not only on the final design but also the work of their Australian colleagues.

Eucalypts of Hodogaya features samples of the 10 different stones used in the construction of CWGC Yokohama. Accompanying them are explanations as to where and how they are used and the cultural significance underpinning these uses. The samples come from Yabashi Marble, Japan’s preeminent stone contractor and the source of the original stone used by the Anzac Agency at Hodogaya.

Another important cultural thread in Japan, Buddhism, has for thousands of years imbued Japanese garden design with simplicity and a contemplative appreciation of the natural environment. Specific features of karesansui (dry landscape gardens) and kaiyu-shiki (strolling gardens) that evoke these principles are also fully integrated into the design of CWGC Yokohama.

The Gardens

John Alexander (Alec) Maisey (1902–91) was appointed the Anzac Agency’s first Horticultural Officer in 1947. He contributed to the planting schemes of all the Anzac Agency’s cemeteries but devised his most sophisticated and expansive landscape scheme at Hodogaya, in concert with a British-born Anzac Agency Inspector Leonard Schofield Harrop (1915–2011) and a local contractor, Tokio Nursery.

The plantings at CWGC Yokohama reflect the various nations buried at Hodogaya—eucalyptus for Australia, roses and oaks for Britain, manuka and maples for the New Zealand–Canadia section and Himalayan pines for India. The cemetery, however, also embraced Japanese azaleas, apricot, cherry, bamboo and zelkova.

Len Harrop had transferred to the Anzac Agency in 1948 from a previous role in the British Army’s War Graves Service. Appointed permanent inspector for CWGC Yokohama in 1952, he would hold the post until 1986. For five decades, Harrop was the ‘face’ of CWGC Yokohama, escorting dignitaries through the cemetery—including, long after retirement, Princes Diana in 1995. Harrop was awarded an MBE for services to the British community in Japan in 1978. Unique among the Anzac Agency team that built it, Harrop alone is buried at CWGC Yokohama.

Legacy

Ultimately, the construction of CWGC Yokohama was a process of ‘mutual acclimatisation’—a softening of the standard design practices of both the Australians and Japanese. Together, the Australians and Japanese achieved a hybrid design acceptable to all—an organic expression of diplomacy.

Eucalypts of Hodogaya is a celebration of the Anzac Agency’s exceptional achievement at CWGC Yokohama and the Australian and Japanese architects, landscapers, horticulturalists, contractors and officials who put aside cultural differences and recent wartime enmity to collaborate on this momentous project. The exhibition also showcases the Agency’s monumental work across the Pacific and the legacy for which the whole of Australia and the Commonwealth can be proud.

Eucalypts of Hodogaya was made possible by exhibition co-curators, Professor Anoma Pieris and Dr Athanasios Tsakonas, upon whose groundbreaking research and tenaciously won contacts the entire project is built.

Author:

Neil Sharkey is the curator of Eucalypts of Hodogaya and Curator: Public Programs at the Shrine of Remembrance.

Enjoyed this article? You might be interested in:

- Shrine exhibition Eucalypts of Hodogaya is on display in the Galleries of Remembrance until July 2026.

- To hear more about the Yokohama War Cemetary, tune into our podcast 'Behind Eucalypts of Hodogaya: A Landscape of Reconciliation' with exhibition co-curators Professor Anoma Pieris and Dr Athanasios Tsakonas.

- Discover more stories from the Second World War here.

Updated