- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

- Service:

- Army

In 1943, Goodenough Island—part of the D'Entrecasteaux Islands archipelago off the eastern tip of New Guinea—became the unexpected stage for what the 5th Australian Division’s Public Relations Office called 'the Greatest Bluff of the Pacific War.'

In October 1942, the bulk of Australia’s infantry was concentrated on mainland New Guinea defending against the Japanese advance along the Kokoda Track. The 600-strong 2/12th Battalion, however, was charged with clearing Goodenough Island of 350 Japanese troops who were cut off in their attempt to reach Milne Bay. The Japanese forces took advantage of the difficult and steep jungle terrain to retreat westward, with about 250 escaping to nearby Ferguson Island.

The 2/12th was withdrawn to New Guinea in December and a small garrison of around 200 Australians was installed to secure Goodenough Island against a possible Japanese counterattack. Allied forces planned to build an aerodrome on the strategically ideal eastern side of the island but feared the garrison would be overrun before support arrived. The Japanese must be made to think they faced a brigade of several thousand men. A clever plan of deception employing camouflage was devised.

Using two primary strategies of camouflage, crypsis (using colours, patterns and shading to blend objects into their surroundings) and mimicry (creating decoys and disguises to mislead), Allied forces set out to fool the enemy.

The elaborate deception, known as Operation Hackney, began at Milne Bay with false radio reports and rumours of troop movements to mislead nearby Japanese forces. On 10 February 1943, a flotilla of transports tasked with delivering the ‘brigade’ to the island departed under Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) protection. Rather than men and weapons, the ships carried ‘wooden packing cases, empty petrol drums, camouflage paint, sheets of tin, hessian, old tents and mosquito nets’—everything required to create the illusion of a large occupying force.

Camps began to take shape on Goodenough. Areas were cleared of grass, tents set up, kitchens built, dumps established, slit trenches dug, weapon pits rigged, barbed wire lined the beaches. Apparently a full brigade had taken up its position along the eastern side of the island. But there was no brigade in the series of camps just one company, scattered widely, and a few score natives.

Fires were lit in the kitchens every day. The dumps—piles of old cases and tins partly covered with tarpaulins—were primed with petrol and oil, and wired so they could be set on fire immediately a bomb fell anywhere near them.

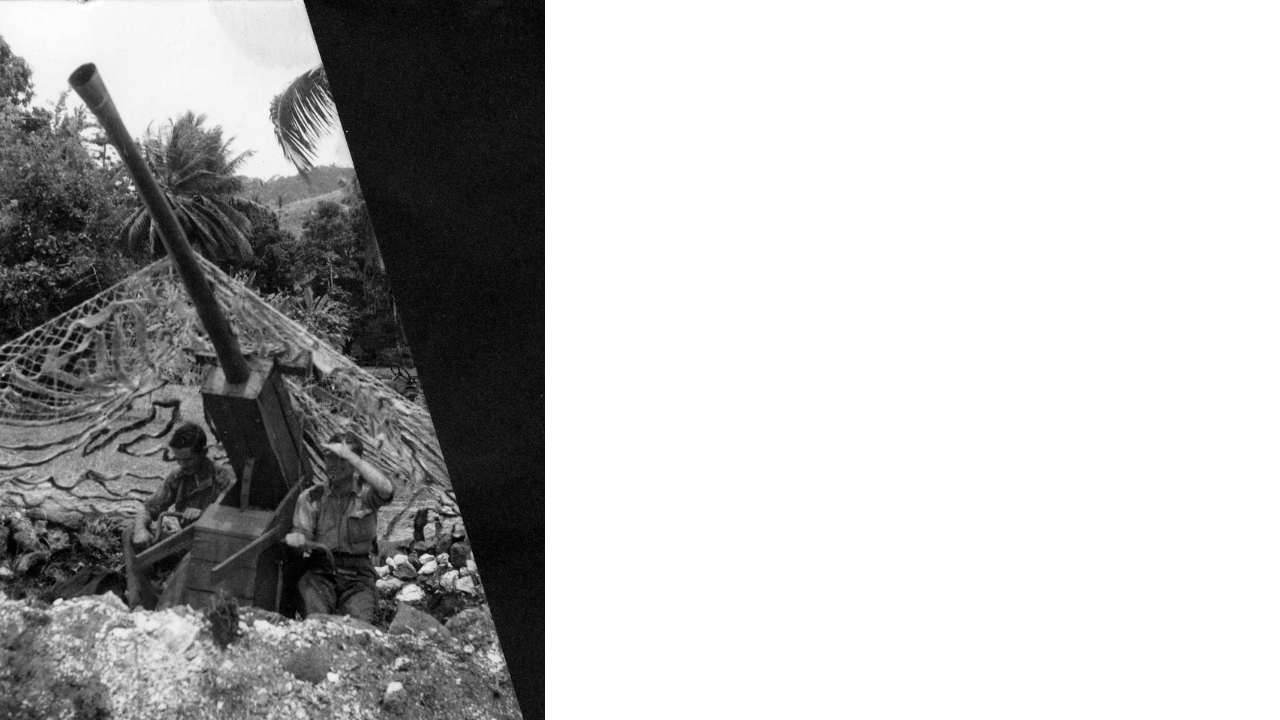

The 25-pounder guns (Bofors) were most convincing… made of wood, tin and hessian. They were set in sunken emplacements, correctly sand-bagged, trenched and netted. One of the simplest and most effective deceptive devices was the apron ‘barbed wire’. Wooden stakes replaced metal, and thin jungle vines replaced genuine wire. From 50 yards this ‘wiring’ was indistinguishable from real wiring. The tops of jam tins were tacked to trees outside to look like shaving mirrors. Washing and blankets were hung on a clothesline [and changed daily]

Army News, Darwin, NT, Saturday 9 September 1944

No detail was too small, with the garrison creating paths between installations, mimicking the traces left by many troops when seen from the air.

The deception was a success—strategically, logistically and financially. So much so the Public Relations Office of 5 Australian Division waived its normal embargoes on publicising the use of camouflage, releasing information on Operation Hackney in 1944. The operation demonstrated Australians could successfully carry out large-scale camouflage deceptions and was influential in the acceptance of camouflage as a legitimate war tactic by some previously sceptical troops and commanders.

Author:

Katrina Nicolson is the Exhibitions and Grants Coordinator at the Shrine of Remembrance.

Enjoyed this article? You might be interested in:

- Shrine exhibition Camouflage is on display in the Galleries of Remembrance until April 2026.

- To hear more about the history of camouflage in the military, tune into our podcast 'Hide and Seek: The History of Camouflage' with Professor Ann Elias.

- Discover more stories from the Second World War here.

Updated