Have you ever wondered how mail was received by soldiers on the front line? In this festive edition of Shrine Stories, Exhibitions Coordinator Katrina Nicolson uncovers a unique Christmas message and unpacks just how complex it was to coordinate wartime post.

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance embraces the diversity of our community and acknowledges the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which this podcast was recorded. We pay our respects to elders past and present.

KATRINA NICOLSON: Mail day is great days. I was reading one chap's letter, and he said, 'When mail call came, you get your mail, and we'd all retire to our separate corners and just read them over and over again and think about the folks at home'. So, it was a really important thing, a really wonderful thing.

LAURA THOMAS: Welcome to the Shrine Stories podcast, a place where we take you through the stories behind the objects on our gallery floor. My name is Laura Thomas, and in this episode, we're getting into the Christmas spirit and unpacking a Christmas message that was sent during the Boer War. Katrina Nicolson is the Exhibitions Coordinator here at the Shrine and joins me now to spread some festive cheer. Welcome, Katrina.

KATRINA NICOLSON: Thank you for having me and Merry Christmas.

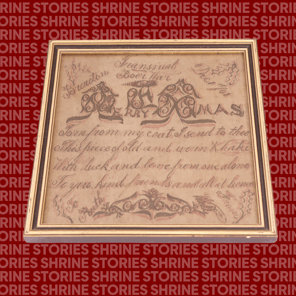

LAURA THOMAS: Can you describe this Christmas message for us?

KATRINA NICOLSON: Well, this is pretty exciting. This is a piece of a Boer War tunic, and it's been inscribed 'Merry Christmas', and it has a little Christmas message. And for people who are unfamiliar with the colours that were used during the Boer War, it's on khaki, which at that stage was a very brown, brown colour. And the inscription is in a probable what was a black ink originally, but it's faded. But he's done some little twiddles and curlicues in red, and he's made some little holly trees and some berries. So, he's making an effort to make a little pretty Christmas card.

LAURA THOMAS: And what does the message say?

KATRINA NICOLSON: It says it's from the Transvaal, which is in what is now South Africa. It says, 'Boer War, December 1901. Christmas greetings, torn from my coat, I send to thee, this piece of old and worn khaki, with luck and love, from one alone, to you kind friends, and all at home. To Ruth, from Will. So, who's Ruth? Who's will?

LAURA THOMAS: Yeah, tell us.

KATRINA NICOLSON: Will is William R Bell, and he and his brother George served during the Second Boer War. He enlisted in 1899 and went to South Africa and served with the second Victorian mounted rifles. And he participated in the fighting at the Black Reef Mine on the Witwatersrand. And he sent this Christmas card poem to his sister, Ruth. So, Ruth was back home in Victoria. They grew up in Victoria. They grew up in Gippsland. And she and his other sister, Jenny, corresponded with him regularly. And you know, there was a lot of mail going backwards and forwards between them.

LAURA THOMAS: So why would Will have used his coat offcut to send this message, like was paper not available?

KATRINA NICOLSON: Well, yes and no, paper was in short supply. So that can be one reason. But what we've discovered, as we've researched this, is this was a bit of a popular thing to do. It's not that there's hundreds of them out there, but there are a few in museums around the world. And interestingly enough, it was obviously a little bit of a fad, because the poem is the same. I've seen several examples with the same poem, or perhaps with the last line different to cater to who they're sending it to, like I've seen one that, rather than 'all the folks', it says 'to my cousins at home', and it was sent to cousins. So, it seems that it was a little bit of a popular thing to do. And whether that was because there was a lack of paper, which is certainly true in any war zone, paper is hard to come by, or whether it was because, you know, it was just a little bit quirky, it was a little bit nice. And sometimes these might have been people who would normally have, you know, perhaps, written their own Christmas messages or decorated a card or something, because it wasn't as easy to buy packed Christmas cards as we have now. And often people did make their own, but we don't know for what reason in particular. But it's just a nice little thing to do a little bit of his uniform. Uniforms wore out really quickly on the sort of campaigns that they were participating in in the Boer War. So, I can imagine he might have had a torn piece quite easily to hand, to use.

LAURA THOMAS: And I imagine the fabric would be more durable than paper with the traveling that this letter had to do.

KATRINA NICOLSON: That's certainly true. If, for example, you know, the mail gets wet or is damaged in any way, a piece of fabric is more likely to come through.

LAURA THOMAS: So, let's talk a little bit more about this, this concept of mail and sending and receiving mail. It's always struck me as quite amazing that soldiers are able to receive items from home during conflict. So how difficult was it to send and receive mail, particularly in the Boer War.

KATRINA NICOLSON: Well, it wasn't necessarily difficult for the people doing the sending and the receiving. The people it was difficult for were the Postal Service, who were charged with doing the deliveries, because that is a huge challenge. And the history of postal service in wartime actually goes back many centuries. And it's evolved over time. And like many things, it starts off as being something that is used by commanders and officers and devolves into something that is used by men. And as early as 1795 the British Army had, there was a parliamentary inquiry into mail and mail for soldiers, and it was recognised at that time that receiving mail was good for morale, and that is something that, you know is still recognised today.

KATRINA NICOLSON: So the British Army were very conscious of the need to assist mail, and they had various tries at it over many years, and in the Boer War, it's beginning to look what we would recognise as a mail service, and that's partially because the civilian mail service has grown as well, so they know how to do it. But it's a really big logistical challenge when you hit a war zone, and particularly the type of war zone that the Boer War was, because it's a mobile war zone, so it's not as though you can deliver things to a post office and go, 'Okay, this unit's here, and we'll just send our bag of mail over to whatever little town or place they're at, and they'll still be there when the mail arrives'. It's not as simple as that. So, what the British Army actually did was they set up a central post office, but then they had mobile post offices, which were using the rail, which was a, you know, still a relatively new sort of idea. And so those mobile post offices would go as far as they could by rail, and then they were using horse and cart to move things.

KATRINA NICOLSON: And when they started, it was particularly difficult, because during that period, it wasn't common for set regimental number to be applied to each person. People were moving around a lot. The units were moving around a lot, and it was a real shamozzle in the beginning, but they established a method, and they did manage to get most of their mail through to people and most of the mail back. But it's quite extraordinary, the logistics behind it, and as I say, it's the beginnings of what we would recognise now in terms of a military mail service. And they applied the learnings from that as they went into the First World War, and then applied more learnings in the Second World War and beyond.

LAURA THOMAS: So, what were those learnings? How did the postal system change?

KATRINA NICOLSON: Well, some of it was due to the fact that the way the armies were organised changed. So, one of the things that became very obvious is, if you've got seven Fred Smiths across your army, somebody sending something to Fred Smith in South Africa or at Gallipoli, Fred Smith is not going to receive his mail. That's, pretty obvious. So one of the things is that during the First World War, every person received a regimental number, and every person was assigned to a unit, and people at home were advised to clearly state the regimental number, the rank, the unit of the person they were sending the mail to. They went to a central position, and then from there they were moved to each unit. Now that still sounds pretty simple, but it's not that simple and where the British Army had a dedicated force of career postal workers with the engineers in charge of logistics, the Australian Army sent over half a dozen blokes and thought that they could handle the volume of mail going through. And of course, they realised pretty quickly that they just couldn't cope with the amount of mail going through, but the amount of redirection they were having to do as people were going into hospital, as people might be deployed on training, all sorts of things were happening, as people died, and it's very important if you're going to return things to sender, you don't want them to arrive before the telegram telling the family.

KATRINA NICOLSON: So, these are all challenges that they are weighing up, and then that is exacerbated, particularly with the Australian Army, because when the Australian Imperial Force came back from Gallipoli. They divided all the units. So, the Australian Postal Service had just got itself organised and was getting itself sorted, and all those people that they had addresses for were moving. So half were staying with the original unit, and half of them were being made up into new battalions, with new recruits coming out from Australia.

KATRINA NICOLSON: And I'll read you this quote from a chap who was involved about how difficult it was; 'the units were split, half retaining its old designation and being filled to strength by reinforcements, while the other half assumed a new number and was also brought up to strength by drawing on reinforcements. The effect of this change, from a postal point of view, was as though half the residents of Prahan had been transferred to Williamstown and had been replaced by a similar number from Carlton. And every suburb over the metropolis was similarly affected'. And I thought 'he's got it', because he was trying to explain why a civilian Postal Service wouldn't work in the military situation, because your street doesn't change, you know. So, once it gets to the post office, they sort the post by street, and off the postie goes. But your unit is moving, so that's the first area of difficulty, and then the people within the unit might be moving as well. So that's the second area of difficulty.

KATRINA NICOLSON: So, what they ended up doing, which followed on from what the British had learned to do, was that the Postal unit was enhanced. They used people who were, you know, recuperating from illness, as well as actual qualified postal workers who came from the Australian post office, and they did tracing. And so, they had cards where they would have listed all the ins and outs from each unit was sent to them. And this, again, sounds simple, but it was a big deal for them to get that. The Army wanted them to go through channels. And they proved to them that it would take two weeks for them to get the information through channels, and by that time, a person could have moved three times, whereas by them getting the return lists immediately, so each unit would send in who was in and out, and so they would have the lists, and they would keep these cards up to date. And so that began in a small way in Egypt, and when they moved to the Western Front, the post office base was actually in London, and they employed a lot of women as clerks, which freed up some of their workforce to return to, you know, active duty. And also, again, employed people who were recuperating on leave, that kind of thing. And it was enormous, an enormous undertaking. To give you an idea, during the Boer War, they were talking about something like in Christmas week, so about the time that our message was sent, something like 300,000 articles of mail in the Boer War.

LAURA THOMAS: Wow, going in or out?

KATRINA NICOLSON: Going in. During the First World War, that was a similar amount on a weekly basis.

LAURA THOMAS: My goodness

KATRINA NICOLSON: It was huge. It's extraordinary the volume of letters, parcels, newspapers were a big thing, just this enormous volume that was going through. And they would arrive at a station in London. They would be ferried across by a very small team of transport drivers. There was only a dozen of them, with some non-commissioned officers in charge. And they would be processed within 48 hours and be on their way to people on active duty in France. Quite an extraordinary achievement. And with all the work that they did, and there is nothing more complained about than a postal service, we do it today ourselves. We all know it, they only had something like 3% of absolutely undeliverable mail.

LAURA THOMAS: 3%?

KATRINA NICOLSON: Yeah, with that volume, it's absolutely astonishing and a testament to the effort that they went to ensure that people were found. And the British were saying to them, 'Why are you doing all this redirecting and chasing people through hospitals and camps and wherever they are? Just send it back to sender'. And the chap in charge, to his credit, said 'It takes 10 to 12 weeks for something to go back to Australia. Why not spend an extra week seeing if we can find them here? It's the right thing to do'.

LAURA THOMAS: And as you said, it lifts that morale, and would have had quite a large impact, for sure.

KATRINA NICOLSON: Absolutely. Mail day is great days because of the exigencies of war, you wouldn't get a weekly mail delivery, and you might get a whole heap of things together, especially if you'd been moving through a hospital situation, or if you'd been deployed to a different unit or something like that, you might get several things packaged up together. I was reading one chaps letter and he said, 'When mail call came, you'd get your mail, and we'd all retire to our separate corners and just read them over and over again and think about the folks at home'. So, it was a really important thing, a really wonderful thing, and also the deliveries home. There's a constant stream of mail going home.

KATRINA NICOLSON: This idea of connection and connection between the troops and families is really important, and it has always been seen as important by the defence forces. It's not something that they've stepped back from. They haven't always practiced it as well as they might, and they've learned how to do things better over time, but it's always been in their minds. It's never been a thing where somebody comes along, they go, 'Oh, why would you want that?'. It's seen as being beneficial, and today, you know, they really do look at it as being an absolute moral necessity. So, in a modern defence force, this is how they view it. 'Mail is morale, and something as simple as a written letter or package from home can make a huge difference in a deployed member's day'. And so, the Australian Army is still making sure that those packages get through, and they partner with Australia Post, Australia Post, do deliveries always for serving members and their families. But they also have two big pushes a year, in the middle of the year and for Christmas, where they will send parcels from the public to people who are deployed overseas.

LAURA THOMAS: It's quite interesting, because we think that generally people sending handwritten letters has probably decreased, but personally, when I receive a handwritten letter or a handwritten card or a parcel in the mail, that kind of feeling, that warm feeling that you get, as opposed to an email or a text or a Facebook message. So, it's great to see that there's still that value placed on it, even today.

KATRINA NICOLSON: Yeah, I think so. One of the things when I was delving into this, because I knew we'd be talking about it, was to look at what happens, and with that bit of an expectation that, yes, digital means have superseded mail, physical mail, and in some ways, yes, you know, because you can be in contact by satellite phone or by video, face time, whatever, so you can have more regular contact more easily. But there's still a place for the physical mail, and there's still a huge quantity of physical mail delivered backwards and forwards between troops deployed and families at home. So, it hasn't, it hasn't gone away. And I think, yes, that physicality of having something in your hand that you can hold that's come from that loved one is really important.

LAURA THOMAS: So, for those listening at home who haven't yet sent your Christmas cards, now is the time. Thank you so much, Katrina for discussing this with me, talking about Christmas, talking about mail. It's been wonderful to have you. You're very welcome.

KATRINA NICOLSON: Merry Christmas.

LAURA THOMAS: Merry Christmas. Thanks for listening to this episode of Shrine Stories. For more, make sure you subscribe to our channel wherever you listen.

Updated