Images of the Shrine of Remembrance today are abundant, but depictions of its construction are rare treasures.

In this episode of Shrine Stories, Collections Coordinator Toby Miller delves into Alexander Colquhoun’s painting of the Shrine being built, uncovering its artistic significance and the personal grief woven into its story.

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance acknowledge the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation, the traditional custodians of the land on which the Shrine stands, and pay our respects to their elders, past and present. As a place of remembrance and storytelling, we honour their deep connection to country and waterways shaped by generations of stories and memories.

TOBY MILLER: Beyond that, it's a very sweet picture. You encounter it when you get to the end of the First World War Gallery, and I think it does reflect the mood of Melbourne at the end of that. It's not a joyous celebration. It is a more meditative, it's a more reflective picture.

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance has appeared in hundreds of paintings over the past few decades, but artistic depictions of its construction are much harder to find. In this episode of Shrine Stories, we're looking at a depiction of the building under construction by Scottish-born Australian painter and art critic Alexander Colquhoun. Toby Miller is the Collections Coordinator here at the Shrine, and joins us now to shed a bit more light on this painting. Welcome Toby.

TOBY MILLER: Hi. Thank you.

LAURA THOMAS: Can you start by describing the painting?

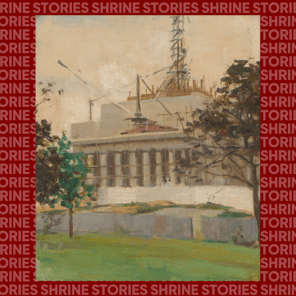

TOBY MILLER: Well, it's a small, little painting. It's very intimate. You'd probably call it a landscape. It's in a vertical portrait format, and most of it is dominated by the picture of the Shrine. It's the Shrine we believe painted around 1931, 1932 because it's not complete and it has scaffolding and cranes sort of obscuring it. We think it was probably painted on site by the artist who would have been sitting down on the Domain near St Kilda Road, looking up towards the Shrine.

LAURA THOMAS: And as I mentioned earlier, the artist is Alexander Colquhoun. Can you tell us a little bit about him?

TOBY MILLER: Colquhoun was born in Scotland, in Glasgow, he's part of a large family, and they moved to Melbourne when he was about 14. He trained at the National Gallery School. He belongs to the generation that we would think of as the one coming just after the most famous, the Heidelberg School generation. So he's a little bit younger than Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton. He's friends with Frederick McCubbin, who becomes a lifelong friend. He graduates and becomes qualified as an art teacher. He is part of the Bohemian set of painters around the turn of the century. He's a member of the, what was called the Buonarotti Club, named after Michelangelo. And within that group, he was friends with Emmanuel Phillips Fox and Judas and George Tucker and in particular, John Longstaff.

LAURA THOMAS: Did he do a lot of paintings of buildings? Was that the area that he was working within?

TOBY MILLER: He was mainly interested in landscape, in the urban environment, a lot of the pictures will be very quaint and not very monumental pictures of little local places where people frequented in and around Melbourne, which is where he did most, most of his painting. Professionally, he also worked as a cartoonist and an illustrator, as most of the artists at that time did, and he would have produced portraits and other pictures on commission, but he's probably most well known for these small urban landscape pictures.

LAURA THOMAS: Why do you think Colquhoun chose to depict the Shrine?

TOBY MILLER: Obviously, the Shrine being built, it generated a lot of public interest. Obviously, the First World War had affected people in this part of the world dramatically, Colquhoun was one of them. And the idea that it was being built and that people knew about it, there would have been a great public interest in it, but I still think it's an unusual choice of a picture, particularly under construction and framed and focused in the way that this one is. There's countless depictions of the Shrine. It's something we often say here is that it's Melbourne's most recognisable landmark. But most of those depictions are the Shrine as the monument that we know it. They're not pictures of it being built.

LAURA THOMAS: You mentioned that Colquhoun was affected by the war. Can you explain that a little bit more and speak particularly about his son?

TOBY MILLER: Well, Alexander, Colquhoun, he was, he was too old and to settled in life, to be involved in the First World War himself. And I think there's probably some evidence that he was, that he leaned towards a pacifist side. But he did have several children, and one of which his eldest son, Quentin, who was known as Queenie, enlisted in the Army in 1915 and sailed for Europe in April of 1916. His battalion was involved in the Battle of Pozières and the Battle of Mouquet Farm in the months prior to his arriving, and they were two of the really brutal engagements for the AIF on the Western Front, and they decimated the battalion. So he would have arrived to a battalion that had sustained immense casualties, and he would have been part of the replacements, and they were obviously involved in a very active part of the front. He arrived at the front in October of 1916 and then he's killed by an artillery shell about a month later on the 25th November, so really not a very long time in the theatre. And the news of his death, it wouldn't have been immediate, but it would have come back to Melbourne shortly after, and as was often the case, there would have been very few details. So Colquhoun would have said goodbye to his son, and then really, the next news he would have received would have been that he'd been killed.

LAURA THOMAS: Do we have any record or understanding of how Alexander Colquhoun responded to this, how it impacted him?

TOBY MILLER: We don't have any clear indication of how Colquhoun, his wife or their family necessarily felt or responded. We can presume it would have been a shock. It was such a short time on the Western Front, but by that time, by late 1916 you know, the casualty lists had been coming back. It could not have been a complete surprise, but it would have been, I think we can say, devastating for the family. Even though they didn't receive a lot of information at the start, they were clearly moved enough to to seek more information. As the personal items and belongings came back, they would have received Queenie's items. There is some correspondence that they communicated with the barracks seeking additional items. And obviously, Quinten was a keen diarist, and they had some inkling that he was keeping an up to date diary of everything that was happening while he was in the army. And there are letters from Alexander to the barracks asking them to look for at least try and find this diary as it wasn't returned with his belongings.

TOBY MILLER: I think there's very little, very little chance that that did come back. We know that from the correspondence between a friend of the Colquhoun's and the Red Cross Missing Persons Bureau that when he died, he was buried in a very informal grave where he was killed on the Western Front. He is one of the 10,000 or so Australians who are buried without a known grave, and whose only details in Europe are those listed on the Australian National Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux. So there's no grave, there's no diary that was probably, probably on his person and probably buried with him. So there is a great gap or gulf of information that comes back to the family and they were not alone in this. It's something that they had to deal with or make sense of, not simply that somebody had died, that you know, that tragedy that all, all too common tragedy, both in war and in daily life, but also this gap, this sort of lack, that they try to fill, or want to fill, or or just have to, in some way, sort of accept that they won't be able to fill.

LAURA THOMAS: And that's one of the key reasons the Shrine was built in the first place, as a place for people to go and mourn their loved lost ones who don't have a grave, who weren't brought back to Australia. Do you think that this loss that Colquhoun felt was part of the reason why he decided to depict the Shrine?

TOBY MILLER: We don't know and we can't know, but it is certainly something that you would suspect - that he's come to the Shrine he's wanted to paint it at this particular point, as it's being built, as it's sort of, you know, each stone is sort of going down. I think he probably did feel that this was something that related to him personally, and was very much a monument, or some sort of way of filling in that gap watching it being built. I don't know. Perhaps he came many times, and perhaps he painted more than one picture.

TOBY MILLER: There are details in trove of an exhibition that he held in about 1932 in which he did exhibit a work called 'Building the Shrine'. We don't know whether it was this one or another one. The inscription on the back of this one is 'The Shrine from the Domain'. And when the work was viewed and the critics looked at it, they appreciated it less for its subject than as its technical or aesthetic qualities. It's when you see the picture, it's a mass of greys, dark browns and whites offset with the garden, which is rendered in a series of greens with sort of little purple, edging and from a technical point of view, there's a lot of interesting things there that are being done with composition and tonal values, but I think with what we learn about his own family, it's quite possible he did come on several occasions, and that the Shrine did stand out, both as something that was visually interesting. It was changing the landscape. It is a commanding position that they increase the height of it to make it more commanding. But as this building went up, it did alter the landscape, both in a visual and in a psychological way.

TOBY MILLER: And I think it's quite possible Colquhoun is responding to that, and I think there is some interest that he is interested in painting it while it's being built, as opposed to when it's finished. I think there's, there's something about the process of it being built and constructed that might, you know, I'm speculating wildly here, but it is perhaps more of a like the process that we do when people die. It's a process. A monument is a final statement, but there is a process of grieving, and perhaps, perhaps that was part of it.

LAURA THOMAS: So with all that said, why do you think this painting is a valuable addition to the Shrine's collection, and why should visitors come in and see this?

TOBY MILLER: Well, we were alerted that the painting was at auction, and we do see from time to time, paintings of the Shrine at auction, when you get a little bit further away from the 1930s it becomes, I think, something more of an icon that people like to capture. It gives you a lot of plays of lights and shadows. But to see one in construction is more unheard of, and our collection is mainly based around things that are donated to us. So this was something we went out to purchase. It's a very small time frame when it's being built, before it becomes the Shrine that it is. It's still a work in progress and so it's very historically interesting for us that people are interested in it being built. It brings that history with it. It's not something that's just received and treated as being always there. So it shows that people wanted it to come into existence, as opposed to just accepting it.

TOBY MILLER: Beyond that, it's a very sweet picture. You encounter it when you get to the end of the First World War gallery. And I think it does reflect the mood of Melbourne at the end of that. It's not a joyous celebration. It is a more meditative, it's a more reflective picture. The Shrine has a long and varied history, and how it's seen and treated and understood varies across time, and the generation that saw it through Colquhoun's eyes, the generation that was very clearly and directly affected, they've gone now, and we can't see it that way, and we will never see it that way again. It means different things to people from this generation. We have veterans who come here, and it's very close to their service, but that First World War generation, the reason for it being built, that chapter is closed, and it's very different. There's lots of photographs, there's lots of newspaper articles, but the life is sucked down of them. So a lovely little oil sketch, whatever the reasons, captures it in a way that we can't experience quite in the same way.

TOBY MILLER: We have recently had it reframed. We did quite a bit of historical research into Colquhoun's framing. We had some assistance from our friends and colleagues at the National Gallery Victoria, who have some Colquhoun paintings in original frames. And they were very generous with information they provided. And we went to a framer that is connected historically to the frame of that Colquhoun used. So we think we're presenting it as close as Colquhoun might have wanted it to be presented. We don't know if he did necessarily want this particular version to be out there. The provenance of the work is that it was connected to the private collection of another artist with whom he was associated through the painter Max Meldrum. It may have been a gift or a swap, and it may have been a very personal item, but we've done our best to reimagine it as a work that he really wanted to put out there. And I think when people come they will enjoy seeing what is a very beautiful little painting that has all these other resonances there if you want to, if you want to learn them.

LAURA THOMAS: Thank you so much Toby for unpacking this painting. It's a wonderful piece, and I hope audiences come in and like you said, enjoy seeing it and the connections that it has with lots of areas of the Shrine.

TOBY MILLER: Thank you. Thank you for taking the time.

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks for listening to this episode of Shrine Stories. For more, make sure you subscribe to our channel wherever you listen.

Updated