- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

- Service:

- Army

When we think of war, we often picture the biggest danger being the guns, bombs, and bullets. But until the early 20th century, disease was actually the greatest killer on the battlefield. In several campaigns, illness claimed twice as many lives as enemy fire.

During the Second World War, Major Henry Shannon played a critical role in the fight against this hidden enemy. Through innovative inventions and educational posters, he worked to protect Australian troops from the devastating impacts of disease.

In this episode, Major Shannon’s granddaughter, Gabby Walters, explores his ground-breaking work and the legacy he left on the Australian Army Medical Corps.

Posters

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance acknowledge the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation, the traditional custodians of the land on which the Shrine stands, and pay our respects to their elders, past and present. As a place of remembrance and storytelling, we honour their deep connection to country and waterways shaped by generations of stories and memories.

GABBY WALTERS: The sorts of things that he came up with to assist with hygiene in the field reflected the fact that they had a lot of 44-gallon drums. He constructed models in order to use these drums to create incinerators for burning off waste, incinerators for dealing with wastewater, so grey water, creating latrines out of 44 gallon drums. And he created pictures about a washing bench and improvised grease traps using cut-up 44-gallon drums.

LAURA THOMAS: When we think of war, we often picture the biggest danger being the guns, bombs, and bullets. But what if I told you that until the early 20th century, disease was the greatest killer on the battlefield? In several campaigns, illness claimed twice as many lives as enemy fire.

In more modern conflicts, illness continued to bear a massive cost on soldiers. At Gallipoli, for instance, dysentery incapacitated more Australian soldiers than Turkish bullets. In these conditions, field hygiene units were not just important—they were vital to the survival of the forces.

Today’s guest brings a personal connection to this part of military history. Gabby Walters is the granddaughter of Major Henry Shannon, who was a physician in the Australian Army Medical Corps. An expert in tropical medicine and field hygiene, Major Shannon served in India, Sri Lanka, New Guinea, and Australia, and worked to protect Australian and British Empire troops from the devastating effects of disease. Gabby, thank you for joining us.

GABBY WALTERS: It's a great honour to be able to do this. Thank you.

LAURA THOMAS: Tell us a little bit about your grandfather. When did he enlist, and why?

GABBY WALTERS: Well, he was born Henry Shaumer, and he changed his name to Shannon at some point after World War One. You know, I think, in an effort to assimilate. He was born in 1897 in Melbourne, and he died at the age of 80 in 1977, also in Melbourne. He had a twin sister and an older brother, Charles and a baby brother, Bernie, who died when he was only eight days old in Broome. His father, Maurice, was a jeweller, and he owned a pearling fleet in Broome in the late 1800s to 1916 and he was also one of the first people to trade opals in Europe from Australia. Our family are Jewish, and he was a member of St Kilda Synagogue, which was founded by his wife's grandfather, Moritz Michaelis.

He and his family moved to London in 1904, and he went to school at Dulwich College. And he spent a year in Germany and in France around 1914 to learn the languages, and he remained fluent in them his whole life. He managed to escape Germany just before the start of World War One, but he noted that that was more by good luck than good design. So, after leaving school, he completed his medical degree at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London, and he completed Doctor of Philosophy at Oxford and a Diploma in Tropical Medicine at Sydney University in 1943 and a Diploma of Tropical Hygiene also at Sydney University in 1944. In London, he worked as a resident medical officer at St Bartholomew's Hospital and also as a House Surgeon there in 1921-22

LAURA THOMAS: So, he's already incredibly qualified, and there seems to be a specific interest in disease control. Can you tell me a little bit about his war service and why that interest existed?

GABBY WALTERS: Well, he enlisted in the Officers Training Corps in London in 1917 and he completed his service in 1919 as a cadet Lance Corporal in the Royal Army Medical Corps. And I've not been able to get a full picture of his war service in World War One, but I do have a picture of a Captain Bill Ferguson on horseback in the Somme in 1916 and he was working as part of the 18th Mobile Bacteriological Laboratory, and that supported treating wounds and infections for the Fourth Army at the Somme. And that leads me to suspect that there was a part of his service that happened there. Also, during the 1914-18 war, visual materials were used in the UK for training in tropical medicine, and that undoubtedly laid the groundwork for his later work in military hygiene education in World War Two. I can see that he became interested in disease control during the First World War, so the context for his work in disease prevention and control lies in the fact that up until the world wars, disease actually killed more soldiers than weapons.

LAURA THOMAS: It's incredible, and it's something that people don't think about when they think of conflict, right, like the guns and the bombs and the things like that, and not the diseases that can get you.

GABBY WALTERS: Yeah, I think in my search through his papers, it became evident that the Army was well aware that disease control and education was actually more important than training in weaponry, because if they couldn't keep the soldiers healthy, they couldn't fight effectively, they had no energy, and they were less likely to return home or they were likely to be evacuated ill or die from disease.

LAURA THOMAS: It was to everyone's benefit that these initiatives took place. So, tell me a little bit about them. What was he doing in this world of disease control during conflict?

GABBY WALTERS: In World War Two, there were many diseases present in the jungles of the Pacific where the war was being fought against the Axis powers, which was Germany, Japan and Italy. There was malaria, filariasis, which is a tropical disease caused by round worms and transmitted by mosquitoes, yaws, which was a chronic skin infection caused by the same group of bacteria that caused syphilis, and dysentery. Malaria, which was a mosquito-borne disease, was often fatal and very debilitating. So he was interested in the public health measures and sanitation measures which could be used to prevent disease and control its transmission via mosquitoes.

Prisoners of war in the tropics were especially vulnerable to malaria, and training for military personnel was highly encouraged, and he set up training programmes which were rigorous in encouraging discipline in hygiene and camp set up, and also the regular taking of atabrin, which was a drug that was chemically related to chloroquine, which was the drug that subsequently became the most common drug in the use to fight malaria. Also quinine, which is related to both of those drugs, was used extensively as an anti-malarial at that time, and supplies of quinine became a very big issue in World War Two, because initially it had come from the bark of a tree in Peru, but Java became the dominant supplier of quinine during the Second World War.

LAURA THOMAS: Why was it such a challenge to convince these soldiers to take up these measures?

GABBY WALTERS: I think probably it was a real lack of knowledge, because they were not medically trained. They were just ordinary people going away to war, so they needed the Army to provide them with that essential information.

LAURA THOMAS: And you mentioned as well that he did programmes to do with hygiene and camp set up. What kind of things was he looking at and encouraging in those spaces?

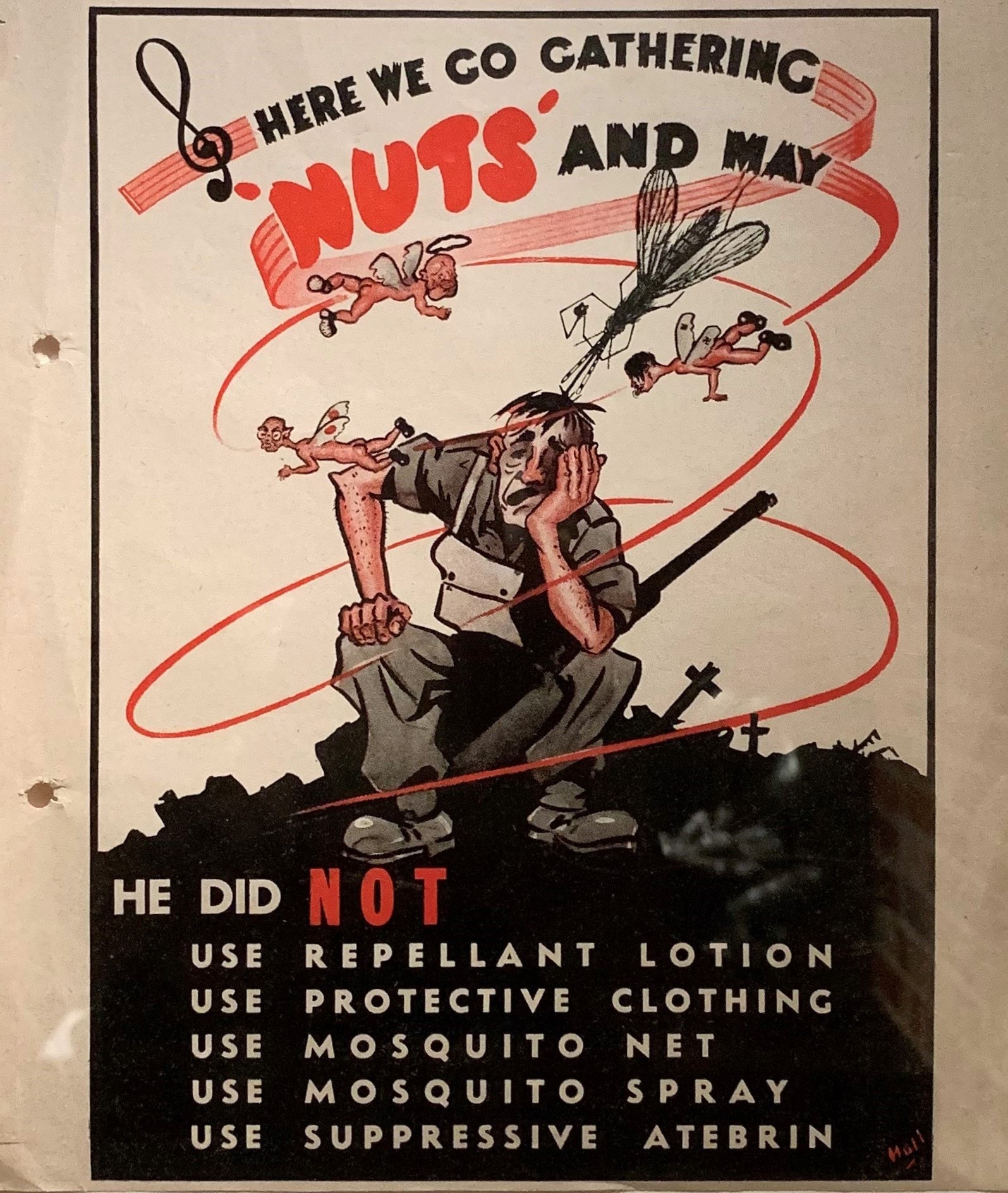

GABBY WALTERS: He was looking at preventative measures for malaria, and he looked at things like filling 44-gallon drums with water and putting diesel oil over the top of them to destroy mosquitoes and destroy their breeding grounds. And also, he looked at mass treatment of troops and the native populations near the troops with atabrin to try and stop the spread of malaria. He looked at public health education regarding malaria and the use of mosquito nets, the careful selection of where armies set up camps so as to avoid areas with high mosquito numbers. He looked at insecticide use on clothes, and he used cartoons as propaganda to try and encourage the troops to take in the information and see its importance. There was one cartoon entitled, Here we go, gathering nuts and may'. And that shows a soldier looking rather dejected, with his hand on his face, and he's surrounded by mosquitoes, and the mosquitoes are drawn to be pictures of Hitler and Emperor Hirohito and Mussolini, and they're buzzing around him, and he's sitting in what looks like a graveyard with crosses around him, and the cartoon said 'He did not use repellent lotion, use protective clothing, use mosquito net, use mosquito spray, use suppressive attebran'. So, it was a graphic illustration as to what would happen if you didn't take those preventative measures.

LAURA THOMAS: And that particular poster is one that we've got on display here at the Shrine. But I understand he did many, more. Do you have any more posters that he did that you can share with us?

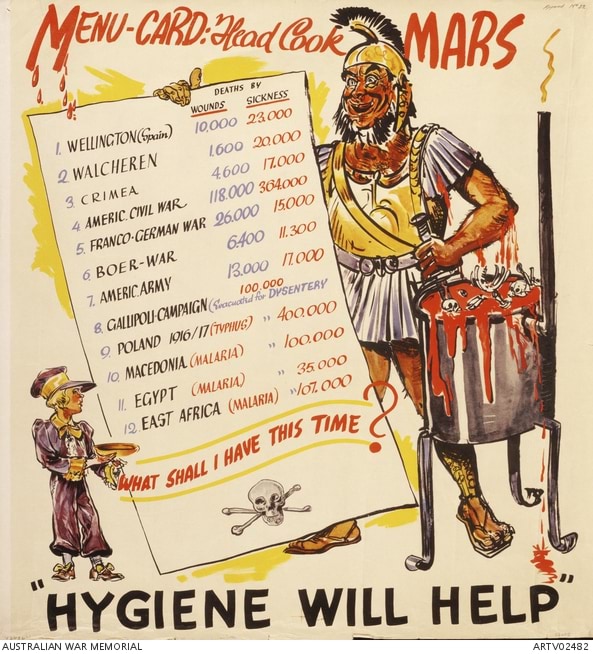

GABBY WALTERS: Yes, he did a menu card with a fierce looking warrior standing next to it, and a little boy who was actually Oliver Twist, saying, "What shall we have this time?" and on the menu, he noted many significant battles, like the Battle of Wellington, where deaths by wound were 10,000 but by sickness was 23,000, in the Crimea, deaths from wounds were 4600 but from illness was 17,000, in the Boer War, 6400, deaths from wounds, and 11,300 deaths from sickness. And he names a number of other campaigns. And at the bottom of the menu, it said, 'Hygiene will help'. So, a simple message.

LAURA THOMAS: And how effective do you know that these were in educating the troops and encouraging them to engage in these healthy sanitation behaviours?

GABBY WALTERS: I don't know really how effective, because, you know, in the heat of war, it's difficult for people to maintain that rigour. But I do know that he was detached to many Army schools to teach military hygiene, and he must have had exposure to thousands of troops over the years of the war. So, he endeavoured his best to get the message out there to them and to make them rigorous in all their attempts to stay well and prevent illness wherever they were going.

LAURA THOMAS: And these military schools that he was at were around the world, weren't they? He travelled a lot during his service.

GABBY WALTERS: He did. There were a number of military schools in Australia. There was one outside Albury called Bonegilla, which started off as a military army education training ground in World War Two, but it subsequently became a staging area for migrants post war. So, he visited schools like that. He also started off in Mount Martha, where there was a training area. And he noted that the tent set up looked like getting ready for the Battle of Waterloo with a number of tents.

LAURA THOMAS: Oh, wow, that's pretty incredible. And internationally, he was travelling as well?

GABBY WALTERS: Yes, well, also in Australia, he went up to Queensland in Canungra, which was another big army training centre. Initially, the training had happened down at Victoria Barracks, and they felt that they needed to really simulate the conditions of the jungle, so they set up training up in Queensland, where soldiers could be exposed to conditions that they'd likely to be facing in the South West Pacific area such as Sri Lanka. So, a lot of the education was informed by direct feedback from the troops in New Guinea so his programmes were altered and adapted to reflect the things that were really essential for the soldiers to know in that area.

He was also in India. He spent 1940/41 in India, and the purpose of that trip was really to educate himself in tropical medicine, and in particular, malaria. And I looked into some of the places that he mentioned that he visited there, he went to a Rockefeller Foundation. And the Rockefeller Foundation in Southern India had a real focus on malaria. And he also visited the Pasteur Institute, which was involved in the treatment of rabies and other diseases in India. He was based in Bombay, but he spent a lot of time at the Haffkine library, which is particularly renowned for all the information that it had on tropical disease. So, he also got seconded to pathology departments, where he was looking at blood samples for people who had parasitic disease. And he was also seconded to the local anti-malaria officer in Bombay to go around and actually look at mosquitoes their larvae. And he was also seconded to an entomologist, so he had experience in actually looking at the different types of mosquitoes and the different types of malaria. And he saw it as most important that he came away with as much knowledge about malaria that he could.

LAURA THOMAS: It sounds like he had such a well-rounded knowledge and education of these diseases.

GABBY WALTERS: I think he did. The Army, I think, encouraged him to go to Sydney University in 1943/1944 to do those diplomas in tropical medicine and tropical hygiene. So, he really specialised in it, and I think that it reflected in his ongoing work in his local council of Malvern with immunisations.

LAURA THOMAS: Was that after the war?

GABBY WALTERS: Yes, that was after the war.

LAURA THOMAS: So this stayed within his life. It's pretty incredible. When he's done so much work in that space.

GABBY WALTERS: Yeah, he had

LAURA THOMAS: Now jumping back to the time that he worked in conflict. Beyond the posters that he made, he also made some pretty incredible inventions, and we've got a couple of the sketches of those in the galleries, but I was hoping you could unpack some of the things that he came up with that would help troops in their protection against diseases.

GABBY WALTERS: The sorts of things that he came up with to assist with hygiene in the field reflected the fact that in the field, they had a lot of 44-gallon drums. And he constructed models in order to use these drums to create incinerators for burning off waste, also incinerators for dealing with wastewater, so grey water, creating latrines out of 44-gallon drums. Coolgardie safe was used for meat preservation, and he created pictures about a washing bench and improvised grease traps using cut up 44-gallon drums. Drums that were used for spraying insecticide. And they used DDT a lot to kill mosquitoes, and they also used sprays to put on clothing to prevent mosquito bites.

LAURA THOMAS: So, they'd be spraying it onto their clothes?

GABBY WALTERS: On their clothes, yes, so they obviously needed to cover themselves, but they sprayed it onto their clothes. No doubt there was a lot of exposure to DDT that probably caused long term illness down the track. And I wouldn't mind betting that a lot of those soldiers ended up with blood cancers as a result of the exposure to those chemicals.

LAURA THOMAS: Of course, but it's when you're trying to protect yourself, the impacts of that didn't come out...

GABBY WALTERS: They just didn't know the long-term ramifications of using those chemicals. There was also a poster that he did about a test called the Horrocks test, and that was very important, and it still is important today, in determining how much chlorine is required to disinfect unclean water and make it safe for drinking. And this is a test which is still used in rural communities to work out how much chemical they actually need to put in to sterilise the water. And he did a poster which shows a number of cups and adding drops of the solution and a dye which would turn blue when a sufficient amount of the chlorine solution had been added to purify the water.

LAURA THOMAS: So, he was an incredible doctor, obviously very crafty, but also quite a writer, because you and I have spoken before this, and you've shown me some incredible letters that he wrote during his service. They're really detailed, and they also have these beautiful watercolours on them, which I think also relate to the posters themselves. Can you share some of the stories from these letters and the interesting places that he went to?

GABBY WALTERS: Yes, in 1941 he wrote, and I quote, "I work in the laboratory of a Parsi doctor, Head of the Routine Pathology Department. I've chosen the whole subject of malaria, which is big enough for the duration of several World Wars. I also felt it incumbent on me to choose a subject which could be said to have a purely army value. They are starting a mobile malaria research lab, hush hush, in one or two parts of the world. And should I be dug out here, I might have a chance of being given a junior job with such a unit". and also, in March 1941 he wrote from the Australian Military Liaison Office in Bombay. I quote, "Our chief is hopping to Australia, and may bring back disruptive news with him. Its nature is pure speculation, but don't be surprised at anything in this war. I'm living here at the rate of about five pounds a week above my board and lodging. The 50 pounds you sent me will run out in about another 12 weeks, unless I am put to unusual outgoings by the coming trip to the neighbourhood of the Luttrells". And the Luttrells was a code word that he had for going into areas, garrisons and active military defence areas. And he mentions that, took me a while to work it out, where it was. And I think in particular, it referred to Sri Lanka, because he called that Luttrells Island.

LAURA THOMAS: And were these all letters to your grandmother at the time?

GABBY WALTERS: Yes

LAURA THOMAS: How often was she receiving them?

GABBY WALTERS: Could have been once every couple of weeks, and there were gaps where he had no time to write, and where he may have been in active combat areas, but he always wrote when he could, and he was always wanting to catch up on the letters from home. And he got his family to number their letters. And he also numbered their letters, so he knew if one was missing or not.

He also commented on the volume of supplies he saw, and I quote, "An increasing quantity of items is being turned out here, including instruments and sterilisers and other quite complex things. It's always a fascinating sight to see common drugs and preparations dealt with by the tons and lakhs (10,000) and crores, (100,000). Tinctures and vegetable drugs are, of course, right up their alley, as the world has always drawn a considerable number of these things in the raw from this country".

And "This afternoon, I went out to the Haffkine library and feeling that I had read enough to find my way around, I had an interview with Colonel Sohkey. I told him I had a few months of light work and a good deal of spare time and would like to go away from India knowing as much as I could take in about malaria. He gave me a place alongside their expert, arranged for me to attend as often as possible the outpatient’s department of the King Edward Memorial Hospital to take bloods for the different kinds of parasite. They state in their annual report that 19,000 cases of malaria attend their outpatients every year. I'm also to work with the Institute Entomologist. As well as this, I'm to go around with the city anti-Malaria Medical Officer to catch mosquitoes, identify them, and learn about their habits and habitats, their diet, human and animal".

LAURA THOMAS: It sounds like he had a real passion for the work that he did, and it comes through in those letters. Would you agree?

GABBY WALTERS: I think so. It sounds like he was obsessed with getting absolutely the most out of every moment that he was in India to learn, and then to be able to apply that when he came back home and set up the Military School of Hygiene in Coogee. and he was the Officer-in-Charge there, and they ran courses, two-week courses, for officers and troops. And he set up a museum of these scale models of articles that could be used in the field for hygiene.

LAURA THOMAS: Such important work. When did he discharge from the army? When did his service end?

GABBY WALTERS: 1946

LAURA THOMAS: You mentioned that he went on to work in immunisations with the Malvern Council. But what else was he doing after his service?

GABBY WALTERS: Following the war, he returned to his general practice for a few years, and that was at his home called Lorraine, which was in Malvern, and that home he subsequently sold to the Cabrini sisters, who ran a small hospital called St Benedict's behind his home in Malvern, and they subsequently built what we now see as Cabrini Hospital on the site of his old home. He eventually became the Medical Officer of Health for the City of Malvern, and he was involved in immunisation programmes. He was also an advisor to the Minister for Health on health education, human ecology and domestic accidents.

LAURA THOMAS: Okay, interesting.

GABBY WALTERS: Yes. He had a wide variety of interests, which he pursued when he came back. He was founder of the College of General Practitioners, and he was later made a Fellow of the College, and he was president of the Malvern Choral Society, and had a lovely baritone voice. And music is a thread that ran through his experience throughout the war and in India, he spent a lot of time going to concerts, singing. He also got together a celebration in 1941 for Anzac Day in Bombay with other expats there, and even recomposed songs like Waltzing Matilda to be able to cheer up people who he knew hadn't been home for about a year. And he used to sing and play with my mother playing the piano. And that was one of the things he really encouraged her as a 12-year-old to pursue while he was away, was her music so that he could sing while she played when he got home.

And he was President of the section of History of Medicine, and also president of the Israel Medical Association. And he visited Israel early in the 1950s, so not long after the State of Israel had been formed, and he lectured frequently to members of the Jewish community about what he'd seen in Israel in those early days. And he had a ketch, which is a ship called the Shamrock, which he had prior to the war. And he used to sail on Port Phillip Bay. And he even sailed in the Sydney to Hobart yacht race one time.

LAURA THOMAS: In his own boat?

GABBY WALTERS: In his own boat.

LAURA THOMAS: Wow, did he finish it?

GABBY WALTERS: Yes

LAURA THOMAS: Pretty incredible. And you were quite young when he passed away. You were about 12, weren't you? What memories do you have of him?

GABBY WALTERS: As a child, my brother and I spent a lot of time with my grandparents, both at their villa in Melbourne, and we also spent our summer holidays with them at our holiday home in Mount Eliza that they'd bought in 1963. He'd take us out fishing on Canadian Bay, and I remember spending the afternoon gutting fish in the garden while he was in the kitchen, getting the fins and scales off and filleting the fish, and then we'd cook the Flathead just in a saucepan with a little bit of butter and eat them. I remember he was fond of a crayfish, and we used to go to the pier at Hastings where we could buy crays. He also liked to barbecue, but unfortunately, he used to burn all the sausages.

He was an avid reader, and he had a library filled with books in his home. All the walls were covered with books, and that was his favourite place in the house to be apart from his workshop, which was at the side of his garage where he used to spend hours turning wood and making furniture. And he used to take my brother and I out there for many hours teaching us how to chisel blocks of wood and make little toy boats and also showing us how to use the lathe to turn wood. He was very strict about hand hygiene, and he always discouraged me from kissing my pet dachshund as he warned that I would catch worms. And in fact, he was correct, but I've always maintained good hand hygiene since.

LAURA THOMAS: As we've already mentioned, you were quite young when he passed away, but did he ever talk about his service, or did you have an understanding of the significant role that he played during the war?

GABBY WALTERS: I didn't. I think I was too young to know. But while I was researching this, I suddenly realised that every night when we were down at Mount Eliza, there'd be a mosquito coil burning in the corner of our room, and it wasn't until I did this that I suddenly understood why we had that coil there every day trying to keep the mosquitoes down back home.

LAURA THOMAS: What do you hope that people take away from this story and his role in disease prevention?

GABBY WALTERS: I think that what I came to understand was how his life back home was disrupted basically for six years, and that he missed seeing my mother and her brother grow up, or he was only there for short intervals when he was on leave during that time. I think it demonstrates that his loyalty was to his country, primarily, irrespective of his background. And that stands, you know, both for his time in the British Army and the Australian Army. I think he contributed a lot to preventing illness in his troops, and he realised it was such a major cause of mortality on the battlefield. I feel like he spent his time well in India, and the enormous amount of knowledge he gained really set him up for all the education that he implemented and the syllabuses that he constructed with, you know, a rigour relating to real war conditions, which must have helped soldiers survive.

LAURA THOMAS: Undoubtedly.

GABBY WALTERS: I think also his skill as a painter and his skill in carpentry, which he obviously developed at that time to make those scale models and set things up when he was in the jungle with the troops, you know, must have had a real impact.

LAURA THOMAS: It's an incredible story and an incredible man who would have had a massive impact on the lives of hundreds and thousands of soldiers. And it's been absolutely wonderful hearing you unpack it. So, thank you so much. Gabby.

GABBY WALTERS: Oh, thank you for giving me the opportunity.

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks for listening to this episode of The Shrine Stories podcast. For more, just search 'Shrine of Remembrance' wherever you listen.

Updated