- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

- Service:

- Air Force

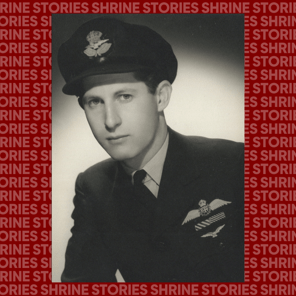

Bomber Command pilots in the Second World War faced horrible odds. With more than half never returning, survival alone was remarkable, but Wing Commander Peter Isaacson’s story goes far beyond that.

In this episode of Shrine Stories, we follow Isaacson’s journey of earning two Distinguished Flying Crosses, leading the first Lancaster flight from England to Australia, and even making headlines by flying under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Later, he played a pivotal role in shaping the Shrine of Remembrance into the place we know today.

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: Bomber Command pilots in the Second World War faced horrible odds. More than half never returned, and flying into that kind of danger demanded extraordinary courage.

In today’s episode of Shrine Stories, we follow the journey of a man who not only survived but excelled, being awarded two Distinguished Flying Crosses.

But his work didn’t stop there. After 45 operational sorties, Peter lead the first flight from England across the Atlantic, the United States and the Pacific to Australia—and the longest flight by a Lancaster. He made history with a feat under the Sydney Harbour Bridge, which you’ll hear about soon, and then went on to help transform the Shrine of Remembrance into the place we know today.

This is the remarkable story of Wing Commander Peter Isaacson — AM, DFC, AFC, DFM. Joining me to tell this story are his two sons, Tim and Tony Isaacson. Thank you for joining me.

TIM ISAACSON: Thanks, Laura. Good to be here.

LAURA THOMAS: Well, Peter enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force in December 1940. What do you think were his motivations for signing up?

TIM ISAACSON: Well, I mean, I think it's probably worth noting at that stage that he was 18 years old, and he actually left school when he was like 16. Hadn't matriculated, matriculated the following year through another source. And then, you know, his dad and mum both identified as Jewish. His dad, Arnold, was pretty observant, I think, and his mum was very liberal and flexible, but what was happening in Germany and the rest of Europe with with Hitler meant that he felt a strong obligation, duty to participate. What do you think Tony? I'm sure, yeah, that's right.

LAURA THOMAS: And there was family history of service in there as well?

TIM ISAACSON: Oh yeah, his dad, Arnold, was the first overseas enlisted member in the Australian Army. Is that right? Tony, and then later, was on the...

TONY ISAACSON: He was on the staff of General Birdwood, was it the British Expeditionary Forces to Gallipoli or something like that?

TIM ISAACSON: Yeah, that's right, yeah, probably the Middle East.

TONY ISAACSON: I think he was an assistant to Birdwood, maybe like an aid to camp or something like that.

LAURA THOMAS: Okay, so a strong family history and a sense of duty. I also found a quote from an obituary that Air Vice Marshal Christopher Jeffrey Spence gave. He was the former Chair of the Board of Trustees, and he said, "When I asked him why he joined the RAAF, he said he was walking down Bourke Street and saw a mannequin in a blue RAAF uniform in the Myers window and wanted to look just like that". It seems he had a strong sense of humour.

TIM ISAACSON: Yeah, he did have a decent sense of humour. Not too bad at all. He was a cheeky bloke.

LAURA THOMAS: He was posted to Canada for his training under their empire Air Training Scheme, and in September 1941 he was sent to Britain, where he joined number 460 Squadron, which was one of the Australian squadrons that was part of the Bomber Command. Now, for those who don't know, can you explain what the Bomber Command was and what they were doing?

TONY ISAACSON: Well, I understand that Bomber Command was, the Allied Air Force was broken up into, I guess, fighters, fighter commands and bomber commands and bomber commands that took the war to Germany, using bomber planes to drop bombs on Germany and on German territory within other parts of Europe. It included bombing of military establishments, strategic infrastructure, and then progressively it extended to the more controversial bombing of cities and of populated areas, presumably arguing that there was military or strategic relevance to those manufacturing the Ruhr and so on. And then, of course, in the most controversial part of it was just really bombing populations and cities, just as I guess the British government would argue, Germany was bombing Europe with rockets and with bombs, bomber planes.

LAURA THOMAS: It was a particularly perilous arm of service. During the whole war, 51% of air crew were killed on operations. Did he ever speak to you about the danger of what he was doing or the losses that they encountered while working with Bomber Command?

TIM ISAACSON: Not that I recall. He would speak publicly about the reason for service. He would speak publicly about the responsibilities of being in the services, but he rarely spoke about his personal first hand experiences. As I recall it, Tony was three years older, so maybe it was different.

TONY ISAACSON: No, same, I think. I think Tim summarised it very well that, you know, he was happy to talk publicly about a public version of of of what he'd experienced, or what he felt, or a message, a political message, to some extent, of of what service meant to him. But at a personal level, it wasn't something that he reflected on with us, and I don't, I don't think he reflected on it. It wasn't like ANZAC day getting together with his mates and reflecting or reminiscing about it. I didn't have any sense that he would be doing that. He didn't do it with us, and I don't think he did it very much with other people.

LAURA THOMAS: Why do you think that was?

TONY ISAACSON: I think he'd, to some extent, he'd moved on from it in his own life or his experiences, and I think it was, you do things that you not just you, whether it's your job or your hobby, you do it. You don't need to. So the certain people, and he certainly didn't and and I understand that, don't need to sort of dwell on it excessively in trying to communicate it to other people. It was, it wasn't necessary to him, it wouldn't have had any meaning, I don't think. What would it have been? Would it have been bragging or reminiscing of suffering or pain? I don't think any of those things, those emotions, were relevant.

TIM ISAACSON: Yeah, I wouldn't mind quoting to you, actually, from a couple of little bits and pieces that he actually wrote at various times in his life afterwards. He did say, well, he wrote, "To some extent, for a wartime pilot to be lacking in imagination is a good thing, and certainly at the time you are doing it, you don't want to be too imaginative. You need to be pragmatic, very pragmatic. You can make yourself pragmatic even if you don't want to be. You can't be too emotional about things like bombing the Germans or Italians. You don't want to dwell on it. I didn't, very few of us did. That doesn't mean that you are lacking in basic sympathies, but you're there to do a job. If you didn't do it to them, they would do it to you". I think the other thing is, you know, these guys were very young. They were putting themselves in extreme danger, and I think it meant that it was a relief to be out of that situation when the time came. I also think, to be perfectly honest, he was a really emotional guy on one level, and the best way to avoid giving into that emotion is to put it aside completely. I think there's a third reason, is that he was only 18 when he started his training, and so by the age of 22 when a lot of his service was happening, he was actually two years younger than Oscar Piastri, and he's doing, he's in charge of a plane that's one of the largest in Bomber Command, and he's responsible for eight people

LAURA THOMAS: It's staggering.

TIM ISAACSON: Yeah, it's pretty amazing,

LAURA THOMAS: Speaking of his age and his achievements at such a young age, att 21 he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal, it was November 1942 at the time, for many successful night attacks on the enemy. How significant do you think this award at such a young age was for him?

TONY ISAACSON: Well, I think it was ... he had a healthy ego, and I think that he liked recognition. I think throughout his whole life, the things that he did, he took a lot of pleasure out of the recognition that he got from them. So I think at that level, he would have been chuffed, and he would have been chuffed that his family were very proud of that, and all the things that go with getting an award. I think it would have been, it would have ended at that because, you know, I think that clearly the next day he was back at work and doing the same thing, or an equally dangerous and that was the focus. So I think it was a benefit, a side benefit, of what was going on. The other thing in balancing what was going on in in the war was sort of his enjoyment of living in London and living in Britain at the time. So my sense of it, we heard more about the things that he would do when he wasn't flying than when he was flying. So I think that, as Tim says, the task was there to be done, but it was, it was a task that was fairly unemotional, and kind of the emotions were probably focused more on the extracurricular activities.

LAURA THOMAS: Things like?

TONY ISAACSON: Things like things like girlfriends in Europe, going out to parties. He was born in in Britain, and he was quite an anglophile, so he thought that it was a big deal, I think, for him to be being taken back to England by the government, in a sense, he wouldn't have done it, he wouldn't have been there otherwise, and he liked it, and he had family in England.

TIM ISAACSON: Yeah, I understand he used to go out to dance clubs and maybe stay up till 3:30 in the morning with some girls. He didn't mind a drink. He'd go to restaurants, and he loved the theatre. And, you know, so West End, to be in the West End was amazing for him. And he could see, as Tony mentioned, a lot of his relatives, who were sort of in various parts of the country, well, various areas around London.

LAURA THOMAS: And I think when we think of service, we often forget the times when they're not in service. They're not directly doing their job, that they were able to enjoy these kind of things.

TONY ISAACSON: Yeah, they have a life that continues on. And my sense of it probably was at Bomber Command it wasn't busy all the time, you know? I mean, there was a lot of time spent preparing planes and waiting and other people servicing the planes, I think. And I mean, he flew more missions than most people and survived it. But you know, the the number of of missions that he flew, he wasn't flying every day to Germany during the period he was there. So there were lots of other things that were happening. And I guess to keep your sanity, those were the things that you would focus on.

LAURA THOMAS: Now he was commissioned as a pilot officer and posted to number 156 Squadron, RAF, with the Pathfinder Force. Now, can you explain who the Pathfinder Force were?

TIM ISAACSON: My understanding, and you know, everything is second or third hand or possibly pulled from a book is that Pathfinder Force was a force that led up to 1000 other bomber planes into Germany to focus on military or strategic targets. And the purpose of the Pathfinder squadron was to go in first, to drop flares to illuminate the target, drop some bombs and then get out of there as quickly as possible. Most of the targets they were going towards were heavily defended, deep into German territory, and there were lots of anti aircraft guns in the area as well, and then they'd sort of get out of there as fast as they could while the rest of the bombing force did their work.

LAURA THOMAS: So he went from very dangerous work to very, very dangerous work. Why do you think he volunteered to do this? Because a lot of them did volunteer and say that they would be part of the Pathfinders.

TIM ISAACSON: Gee, I've actually no idea, except that to some degree, he was a risk taker. And certainly, you know, both in business and in life, and certainly in his later life, his motto for living was, apparently, and it's not an original quote, was, "When in doubt do the courageous thing".

LAURA THOMAS: It's incredible, really. And he had a lot of close calls, as you would imagine, being in that kind of dangerous work, and one of them was during his time at the Pathfinder Force. This was another event that awarded him with the Distinguished Flying Cross on the 30th of March, 1943 and we do actually have a recording from a This Is Your Life episode where Bob Nielsen, who was Peter's navigator, unpacks what happens.

EXCERPT

JOHN MCMAHON: Your name was in the headlines in 1943, Peter, but you knew then, as you know now, that headlines don't make the man, and there's no time to be a hero when your insides are crawling with fear, and you know that you have a plane full of human lives to get back to safety in England. So it's Berlin now, Peter, your first raid over Berlin. You were hit by incendiary bombs from the plane above you and flanked from the guns. Your gun turret was shot away. When you saw the gun turret gone, you were sick at heart, because you thought the gunner Tiger Groves had gone with it. You said something then Peter, which, which, I won't ask you to repeat. And then you couldn't say anything, because you dropped in one sickening moment from 18,000 to 4000 feet. Come over here. Bob Nielsen, tell us the rest of this story.

BOB NIELSEN: Yes, John, by now, we were the only plane left in the area. All the flak and search lights were focused on us. 20 minutes, we were caught in a can and we're only 900 feet above the ground.

JOHN MCMAHON: And tell me, Bob, what were you doing while all this was going on?

BOB NIELSEN: It's an easy one. John, I was saying over and over again, "If I get out of this, oh Lord, I'll never do anything wrong again".

JOHN MCMAHON: And Bob, what was Peter doing?

BOB NIELSEN: Peter was doing the greatest bit of flying he'd ever done in his life. He got us down so low that the guns couldn't sight on us properly, and then he headed for home.

JOHN MCMAHON: Home. That must be a wonderful word at a time like that, Peter. How did you feel when the search lights dropped behind you, when you were out of the flak and you thought for the first time that you might really reach home? Well, Peter, tell us.

PETER ISAACSON: It's a long time ago now, John, I don't remember, but I think I felt pretty thankful, and I felt clothed again, I think, after the nakedness of the search lights.

JOHN MCMAHON: You did, Peter, thank you, Peter.

LAURA THOMAS: He sounds, despite the circumstances, very calm, cool, collected, and maybe it goes back to you saying he saw this as a job that he did, and he did his job, and that was it. What are your reflections on that excerpt?

TIM ISAACSON: Yeah, well, apparently, while he was doing that, there was a guy in the, the front gunners turret lying on his tummy, I think Alan Ritchie again, giving him directions about how to fly through and avoid the rooftops. Look that actually doesn't really even sound like his voice, but I'm sure it is him. I think it was, yes, absolutely, a case of, I think he was really good at compartmentalising, and I think he was going, you know, this is what I got to do, and this is what I'm going to do. In fact, Bob had given him some other advice, which was to fly south and not fly directly to what they believed was London, but he made a decision which was very rare for him to contradict Bob the navigator, and decided to drop the plane really low to get through because by that stage, the plane had been damaged extensively. Joe Grose had been injured in the face and was lying flat on morphine. So I think it was necessary for him to make a decision quickly, and he knew he could rely on his team to back him.

LAURA THOMAS: And did you know this from conversations with him? Or again, this has all come out afterwards?

TIM ISAACSON: Nope. Bob Nielsen, the navigator, wrote an amazing, I think, 900 page book about it and then that got made into a second book by Dennis Warner, the journalist and author. And he used sections of the Bob Nielsen book.

LAURA THOMAS: Now moving away a little bit from his service, but still in that realm. In May 1943, Peter was chosen to Captain a Lancaster called Q for Queenie on a very special flight. Tell us about that.

TONY ISAACSON: Well, the flight was the first flight from Britain to Australia, east to west. So that was the significance of it as a flight, but it was essentially to bring a Lancaster back to Australia for the purposes of fundraising and the war bonds activities. So he and a crew, a version of his crew, bought, I think, Queenie Six, and then spent a period of time touring Australia for fundraising purposes. So they visited towns and cities all around Australia, and effectively sold bonds. And there was, I think, walking through the aeroplane for five pounds, I think from memory, and and, and a flight in it for 100 pounds, or something like that,

LAURA THOMAS: Probably wouldn't pass the workplace health and safety laws today. Just go up, pay $100, 100 pounds, and then off you go

TIM ISAACSON: Yeah, but, you know, it was a public relations exercise. They were an all-Australian crew. They brought out a significant member of the English establishment. I can't remember who that was, Lord, somebody or rather, or something like that. And you know, it was a barnstorming exercise. So because of the size of the plane and the distances it could travel, it meant that it could fly to all these different regional towns and encourage people to pay money to the government to keep the war going. And I think Peter in most of those cities, he was only 22, he was a good looking guy. He used to speak from a podium in all the aerodromes or the fields where they landed, and there would be a huge number of locals would gather and check out the plane. I think it was really exciting. I mean, I've met, this is, you know, this is firsthand, I've met several people who can tell stories about either their parents or them seeing the plane fly over their school or buzz the local church, that is to say, swoop over the local church and then land in the field at the edge of the town.

LAURA THOMAS: I guess when the war in Europe is so far away, to see that firsthand and to be able to experience something of what was being used at the time would have been pretty significant for people every day.

TONY ISAACSON: Yeah, really significant. I mean, I think it's an attempt at sort of creating a little bit of PR, you know, he's working as an influencer. And you do have to remember, of course, that Peter, prior to the war, had been involved in newspapers, so he understood the purpose of public relations and the purpose of creating an event that would be newsworthy.

LAURA THOMAS: Speaking of newsworthy, shall we talk about the Sydney Harbour Bridge Event?

TONY ISAACSON: I suppose this was the most famous, or the best known of the activities that related, the most publicised of the activities related to the period when he was taking a plane around Australia, as Tim described for the people in country towns, the experience was firsthand, but he flew his Lancaster under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. And that was a story that went beyond the people of Sydney, or beyond the people that saw it happen. So it was publicised these versions of photos and doctored photos and manipulated photos of what it actually, what actually happened. And then there was a sort of follow up of publicity over, over this, over it as well. So it was a sort of highly effective media event, I think is how we term it now.

LAURA THOMAS: Do you think he did it because he wanted media around it and more eyes on what was going on in conflict and in the war?

TIM ISAACSON: There's no question in my mind that that's why he did it. You know, once again, it's a question of do the courageous thing and appreciating what's required to achieve a result. And you know, his background in publishing and newspapers, slight as it was, and the fact that his mother was a journalist, knew that he had to develop a hook to get that publicity.

LAURA THOMAS: Did he face any repercussions for this?

TONY ISAACSON: Allegedly. Look, I'm not sure that we know or can separate the sort of the myth of the story. It's a story that's now in our family or in the story of Peter's life is the most myth worthy, I think. So, it's rather hard to tell. So the story is that he did it without notice and without permission. And I think the story was that there was a plan to court martial him because he'd broken ... I don't think people were too sure what was wrong about what he'd done. But there was a sort of whether it was breaking the law, or breaking a military law, or using an aeroplane without approval for something, you know, all the things. And I think that the story is that Air Force and the state government maybe couldn't agree on which was the law or which was the jurisdiction that he'd broken. So there was this discussion that he was going to be court martialed. But, you know, maybe that wasn't the right thing to do, so maybe he should be charged. No, that wasn't the right thing to do. And then, of course, the the value of it and the publicity, perhaps the the controversy, just kept the, in our terms, terms, kept the story in the media. So it was they were perhaps happy to do it. So I don't really have a sense of how real any of that was or, or whether it is just a myth.

TIM ISAACSON: I think he's, you know, I think, obviously he was putting his crew at a bit of risk, but I think they were really keen to be put at that risk. Once again. Know nothing firsthand. It just, I think it's lost in the mist of time

LAURA THOMAS: And Q for Queenie remains the largest aircraft to have flown under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. So that's a claim to fame.

TIM ISAACSON: Yeah, absolutely. The only other planes that have been under the Sydney Harbour Bridge, I think, have been single prop Cessnas. As far as I know, in what year was it? We must have been about 2003 was it Tony, or was it 2013 maybe?

TONY ISAACSON: 90th birthday

TIM ISAACSON: Oh, that's right. It was his 90th birthday. We as a family with his grandchildren and Tony's partner and my partner, did a walk over the bridge

TONY ISAACSON: With Peter

LAURA THOMAS: Did he share any reflections during that walk?

TIM ISAACSON: Nope.

TONY ISAACSON: No, that's the same sort of story, really.

LAURA THOMAS: What did he go on to do after the war?

TONY ISAACSON: He went back to journalism initially, and then pretty quickly after that, set up a business. His mother was a journalist. He saw himself initially as a journalist, and then saw himself as a publisher, and he was he saw that distinction as quite significant. He was interested in producing magazines or newspapers or whatever he was publishing, the different things that he published. So he saw himself as a business person, perhaps an entrepreneur, to some extent. He continued to to write and fill the role of the journalist. And I, you know, his staff would sort of say that Peter was a, if you worked for Peter as a journalist, you'd say, "Oh, Peter was a good journalist". If you were in the sales part of the business, you'd say, "Oh, Peter was a great salesman". But Peter just saw himself, his interest was in publishing, you know, in a broader sense.

TIM ISAACSON: There was a brief moment when he sort of tried to enter politics, just unsuccessfully. But according to him, it was one of the best things, once again, I've got this out of a book, it's one of the best things that didn't happen to him. And then, of course, he continued his his interest in the Air Force and in the Armed Services via Legacy and also via the Shrine of Remembrance.

LAURA THOMAS: Exactly. So he was a Trustee and then the Chair of the Board of Trustees. So very significant figure within the Shrine's history. And I've actually got an interview from ACMI, the Australian Centre for Moving Image, where he speaks about his time at the Shrine.

EXCERPT

PETER ISAACSON: Soon after, I felt that it's about time we thought about what could be done with the Shrine to make it more user friendly and to make it less sombre. So we formed a committee for the future. The first thing we did was to look at the undercroft of the Shrine. The undercroft is everything below the ground floor. We went down and had a look at it, and it was just a massive problem. And we thought at the time, this is a wonderful space that should be used.

We appointed an honorary architect, Rod McDonald, and he inspected the area and came up and said, "Well, the space is magnificent. It can be used, but there's two problems. One is that the supports of the Shrine have got concrete cancer, and secondly, the surrounds need replacing". So "Okay, Rod, that's fine. What's this going to cost?". He came up with a price of 3 million. We had no funds, of course. Joan Kirner was the Premier at the time, and she was very sympathetic. And she said, "Well, Peter, you know, things are tough". I said, "Yes, Premier" ... "but I'll give you one and a half million if you raise the other one and a half". And it's not easy to raise one and a half million dollars to restore some pillars of a building when it's got concrete cancer.

I had a friend, Peter Derron, Sir Peter Derham. And Peter Derham was a marvellous fundraiser. I asked Peter, would he chair a fundraising committee to raise one and a half million dollars? So we raised the money, we had drawn up plans with the help of some consultants as to what could be done now with this area on which we'd spent 3 million, and we gave it the name of the Galleries of Remembrance.

In the galleries, there'd be areas which would show people how the armed forces and the civilians lived in times of war. That was the reason why we wanted to have within the Shrine, but apart from it, something that showed the people what they were coming up to remember, people who had no association with either of the armed forces in any way at all, would come see what their forebears went through, how their families lived. And then they would say, yes, we know what the Shrines remember. Then they would come up to the Shrine, probably, and go round it, and then they would understand.

LAURA THOMAS: So there's no doubting that the Galleries of Remembrance is one of the most significant parts of the building and the biggest development since it was built or opened just over 90 years ago. Why do you think this was so important to him, to have this space for people to come and reflect?

TONY ISAACSON: I think it was the outcome justifies his interest in it. And I think he you know this is, this is a quite outstanding space, in my opinion, well, an extraordinary addition to the to the Shrine as it was, and totally deepening your ability to engage with it. And I think he understood that he, reflects on that, in that, in that recording. The strong thing is, I think that was his vision, and that was his expectation of what it would achieve. And I think he was very keen to leave a legacy of his own. So I think there was a personal, he was very committed to it. I think he, yeah, I think that was probably his aim, was to have a legacy.

TIM ISAACSON: One other component to that, or an additional component to that, which is that, I can't remember what time this process, what year this process started, but I'm pretty sure it was after the Vietnam War demonstrations, and I'm pretty sure it was after some of the other localised conflicts that Australia had been involved in, where sentiments towards the armed forces had altered. And he appreciated, and thought it was really important to help people connect with the the pain of war, the difficulties of war, and the reasons why one might have to risk one's life, to go to war.

LAURA THOMAS: It's a really, really important sentiment, and it's why the Shrine stands today and why we have so many school groups come through. Because for generations at the moment, they might not have a direct connection to conflict, but we know that history repeats itself, so it's important that we keep this message, and it's an incredible legacy that he left. Do you have memories of him bringing you to the Shrine at all?

TONY ISAACSON: Yeah, we would come both for ceremonial times when he was either a Trustee or the Chair for events, not just Anzac Day, but for quite a number of other ceremonial activities that were held here. He would bring us and we would visit other times. I mean, I can remember visiting the undercroft before it was redeveloped, just sort of, you know, going in and having a look or thinking about it. So there were times when we would come with him to those as well.

TIM ISAACSON: He had other engagements as well that were military service related, such as the Air Training Corps, which he took a great interest in. And of course, Legacy.

TONY ISAACSON: I think, as well as Legacy, Peter, had a long involvement and interest in Melbourne 21 Squadron, which was citizen Air Force squadron. He was commandant, I remember many times visiting the North Melbourne Drill Hall, which is where they were based, and that, the Shrine, 21 Squadron and Legacy were the three pillars through which he maintained continuity and interest in things related to the military and his war service and so on.

LAURA THOMAS: Obviously, his service meant a lot to him, and to be able to continue to talk about that and promote support for the services after his career seemed to come through very strongly.

TONY ISAACSON: Yeah, that sort of comment that from 18 to 22 or 23 was his war service period was incredibly short, but he took from that a reasonable chunk of his subsequent interests in life and activities in life.

LAURA THOMAS: Peter's story is one of many on display at the Shrine in the galleries that he helped develop. What do you hope people take away from this story in particular?

TIM ISAACSON: Well, I think from his story, it's one of service, one of commitment, the need for courage, I guess. I'm not really sure I've got a good answer to that.

TONY ISAACSON: Yeah, I think the same. I mean, the general themes of his service are the takeaways that Tim's mentioned. And I don't think he would sort of think that there's anything in particular. I mean, I think he'd be fully appreciative, and we should be fully appreciative that all these stories are, whilst they might be slightly different and nuanced, they're the similar themes, I'm sure. And he'd be sort of pretty happy if he was just one of those, I think.

TIM ISAACSON: Having had a moment to reflect on it, a bit more, I agree with exactly what Tony's saying. But I think what comes out of his story and all these stories, is when you're going through the displays, the best feeling you can have is these people are just like you. You know that their choices could be your choices in a desperate situation.

LAURA THOMAS: Thank you for those reflections, and thank you so much for coming in today and sharing this story. It's been absolutely fascinating. Thank you.

TONY ISAACSON: Thanks, Laura.

TIM ISAACSON: Thanks, Laura.

Updated