The Shrine Stories podcast takes you on a deep dive behind the objects in the Galleries.

In this episode, we uncover the story behind the song, Dream of Australia, which can be heard playing as you explore the Galleries. Petty Officer Ted McHaffie composed it in 1936 during a particularly lonesome and frustrating time in his service.

Tragically, five years later, Ted was one of the 645 Australian soldiers killed when HMAS Sydney II was sunk by a German raider, and so the song was never recorded.

That was until Ted’s nephew, Dr Robert Hoskin, decided it was time that this tune had an audience.

Music:

Across the Line - Lone Canyon

Transcript:

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance embraces the diversity of our community and acknowledges the Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which this podcast was recorded. We pay our respects to Elders, past and present.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: What I think happened, was that he was listening to the men around him and putting their thoughts in words as being a poet. And he said the whole crew were singing it and enjoying it.

LAURA THOMAS: Welcome to the Shrine Stories podcast – a place where we take you on a deep dive into the stories behind the objects on our gallery floor.

In this episode, we’re headed into the Navy section of the Shrine, where as you wander through, you’ll hear this song playing…

DREAM OF AUSTRALIA: When I’m back in yesterday,

Travelling down a road so gay,

All my thoughts are in a southern land.

LAURA THOMAS: It’s a nostalgic piece that speaks about wattle and beaches and essentially, all things Australian, and it was written by Petty Officer Ted McHaffie. As you’re about to hear, he penned it in 1936 during a particularly lonesome and frustrating time in his service…

Tragically, five years later, Ted was one of the 645 Australian soldiers killed when HMAS Sydney was sunk by a German raider, and so the song was never recorded.

That was until Ted’s nephew, Dr Robert Hoskin, decided it was time that this tune had an audience. Robert joins me now to shed some further light on Ted’s life and why this song is so important…

LAURA THOMAS: Welcome, Robert.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Oh, thank you.

LAURA THOMAS: Now, can you start by telling me a little bit about Ted because he enlisted when he was just 15? Didn't he?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Yeah, look, he's a fascinating man even though I didn't meet him. His father died when he was 11, which complicated his life and being around his mother, who was a bit possessive, I think he wanted to get away and join the Navy as you do.

LAURA THOMAS: So he was looking for a bit of an escape...

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Yeah. And adventure. He called himself a rover

LAURA THOMAS: Okay, meaning What?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Meaning that as much as he was a home boy, he was an adventurer, someone who wanted to get out and about.

LAURA THOMAS: And what did he do when he was in the Navy?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Well, he started off, the normal things of becoming a rating and then going through on various ships, the Australia, the Anzac, one of his poems, he says 'it proudly flew the British flag in those times'. But he went through all the different ships, and then decided that he wanted to paint. To be a painter.

LAURA THOMAS: Of ships?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Of ships, which is really the task of keeping them afloat.

LAURA THOMAS: Did he enjoy his work as a painter?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: I think he did. It mixed well with him being a creative person. I'm not sure that he would have graffitied the ships or whatever. Possibly he would have liked to. What it did do was that it gave him time to be close to his mother. Although he'd left her to be the adventurer, I think he felt guilty that he was away. And she was always, as a widow, in need of support. So being a painter, he could spend a lot of time Crib Point at the HMAS Cerberus, and go through the various ranks.

LAURA THOMAS: It took him abroad as well didn't it?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Oh it took him abroad. It certainly took him around Australia in the early ships. And then later, when they went to pick up the HMAS Sydney II, then it took him to England. Lucky man.

LAURA THOMAS: So Ted was due to arrive back to port in November 1941 aboard HMAS Sydney, but the cruiser and her men never made it home. So Robert, I was curious to know about how your family learned about this and the news that they received at the time.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: The problem of the loss of the Sydney was it was kept secret. And it was such a devastating blow to the Australian people, because Sydney was a star ship, that the press weren't able to give it any play. So that how my grandmother received it was via a short telegram. And that's not really a good way to receive his son's death.

LAURA THOMAS: No, no. And how did she react?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Well, she was a staunch woman. But I think what she'd learned was never to express that reaction, except through her music. But I expect that would have been devastating. absolutely devastating.

LAURA THOMAS: When you were growing up, did you hear a lot of stories about Ted? Was he spoken about quite a bit?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: My middle name is Edward, as Edward is Ted. And so in a sense, I was marked, and marked to hear the stories and take his life on in some way.

LAURA THOMAS: And coincidentally, in a lot of ways do that here at the Shrine as well. Which we're going to talk about now.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: So here am I

LAURA THOMAS: Exactly, exactly. Because you came across some things when you were cleaning out your father's home, didn't you?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Well, often my life happens by chance. So the by chance in this episode was my father had said to me, 'Son, one day, all this will be yours'. And what I realised later was I inherited a lot of mess. So when you inherit a mess, the best way is to get a skip, and load it all onto the skip. I fortunately had a good friend who's a bit of a hoarder. And he stopped me at one point said, 'Robert, look what you're doing! You're taking these letters and throwing them out!' So I decided to have a look at the letters. And they were the letters obtained from HMAS Sydney II, wonderful letters.

LAURA THOMAS: Thank goodness for Colin.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Yeah, look, I'm so grateful. I don't think I'd be sitting here without him.

LAURA THOMAS: Tell me a little bit about what the letters said. What was in them?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: What was in them was, Ted had gone to Europe to collect the HMAS Sydney, and on the way, he'd gone at HMAS Brisbane, and that itself was an adventure. But going to London, and Portsmouth and other parts of England, what he learned was the capacity of the Sydney. In some of the letters, he speaks of this brilliant new warship, that will kind of be the answer to the German pocket battleships. Now, I think that was the attitude of Australians. They saw this new cruiser and others as being the answer. And it makes the whole Sydney loss, so much more poignant. But on the way back from London, he was caught up in the Mediterranean struggle. Mussolini had invaded or was going to invade Abyssinia. And Britain said no, and decided to put a blockade on the Mediterranean and Australian warships were involved, including Sydney. So instead of being home by Christmas, is what they were told, it would be months before the blockade would be finished. And they got homesick. They also got mumps at one point

LAURA THOMAS: Gosh, the poor things.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: So in the letters, it gave me this detailed account of what it was to be in the blockade, and I guess he in the main got very bored.

LAURA THOMAS: I can imagine

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: But being so bored, he then had written all these letters, about what it meant, and then wrote the song.

LAURA THOMAS: Now let's talk about the song. Dream of Australia.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Yeah, Well, I guess he was thinking about Australia, as I do occasionally, when I'm in the Kimberley or West Papua or whatever, I think of Australia. And these images of home come. And in his case, I think he was really talking to the sailors of the bush images, and the dog or the country woman and so on. And that's expressed in the words. So 'When I'm back in yesterday', well, that takes you right into it. 'All my thoughts are in a southern land', the whole ship would have had that kind of thought for the southern land caught in the Mediterranean. 'Walking far under the sun, first the wattle then the gum', they're classic images of Australia. We have them for our Olympics. The yellow. 'The fragrant odours seem so near at hand'. 'Once more with a kangaroo'.

LAURA THOMAS: Does it get any more Australian than that?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: I fly Qantas.

LAURA THOMAS: And have some Vegemite.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: So I think what he was trying to do, was to get to those classic images of Australia. Ted wasn't a country boy. He was very much a city man. But what I think happened was that he was listening to the men around him. And putting their thoughts in words as being the poet. And he said the whole crew was singing and enjoying it.

LAURA THOMAS: So it became somewhat of an anthem for the ship and the beautiful longing for home?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Yes, that's right. 'Not a thing that might mean home to me, while a gentle scene comes wafting from Australia, there's a tang of beach and shingle, just as strong as can be.'

LAURA THOMAS: Did he attempt to have it published?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: He did.

LAURA THOMAS: Okay. Why do you think it didn't-

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: I have no idea.

LAURA THOMAS: It's a beautiful song.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Yeah. I have no idea. He got his mother and my mother to go to Alan's Music at the time and try and get it published. But who knows. And I grew up with it. My grandmother, after she was widowed, she played at the silent movies. And so she's a good pianist. And there are two major songs I remember from my youth. And that was Hey Ho Silver, the William Tell Overture. You remember that?

LAURA THOMAS: I can't say that one's in my -

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: (Sings tune) William Tell Overture and of course, Dream of Australia.

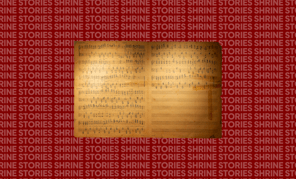

LAURA THOMAS: Now just to clarify the sheet music wasn't found in your father's things, was it?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: No, it wasn't. It was more letters. The music I've got from Grandmother, but I wouldn't have gone there but for those letters. What the letters did was made me do something that was very hard. I think many relatives of people who've died on the Sydney and other ships find it very hard to, even though I haven't directly experienced the grief, I was born with it. It was like passed on to me. So it made it very hard to directly go to it.

LAURA THOMAS: So why did you think it was important to then record this? Because the one that we have, the recording that we have at the Shrine is recorded by you and a good friend and your daughter in law. Why did you decide to immortalise it, I guess, in history?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: It was my way of getting to Ted. I'm an only child. And my uncle Ted had died before my birth. And he's such a creative man. I think I could have really taken so much from his creativity. And here was my opportunity to connect with him. And fortunately, I had a brilliant daughter-in-law who could sing, and an equally brilliant friend who could play the piano and take me back into the '30s because she had the ability to be able to play with that '30s style.

LAURA THOMAS: Tell me about that process of recording it. How did it feel for you and what stood out?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Very emotional. It felt that, again, as I say, a connection with Ted. And feeling that, having read his letter from that time where he wanted it published and thought it was going to be a great seller. It never did. And so here was my moment of making it true for him.

LAURA THOMAS: And how did it feel to hear it and how does it feel to hear it still now play in the galleries here?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: It feels, I'm very proud of Ted. It's a way of saying to myself, 'I am proud of my uncle and all that he has been and done, both for Australia and for our family'. And I'm excited by the fact that in this honouring of war, and so many stories of death and loss, there's a real human element in that song. So for me, it's to come home in a way. And it's been very important to see Ted's last letter in the exhibition.

LAURA THOMAS: Yeah. Can you talk to me about that, because we do have a case that has a lot of Ted's belongings, and one of them is his last letter.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: It was so poignant that in his last letter, he kind of almost knew in advance that he wouldn't be coming home. And he says, he ends his last letter, which was written from Fremantle, just before he got on the ship to go to his death, 'The article was well written, and above all there is, in anything these days, is faith and loyalty. You say 'Do I get emotional?' I get emotional when I hear those words.

LAURA THOMAS: With that in mind, why do you think it's so important that we continue to share stories like Ted's?

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Because you're not alone. Because there are so many people from all the collective wars and their families where in sharing the grief, we have, we're not dealing with alone. We're dealing with it together.

LAURA THOMAS: Thank you so much for sharing this story.

DR ROBERT HOSKIN: Thank you.

LAURA THOMAS: We're going to leave you with the full version of the song Dream of Australia, performed by Robert Hoskin, Kelly Hoskin and Mary Doumany, and of course, with lyrics written by Petty Officer Ted McHaffie.

When I’m back in yesterday,

Travelling down a road so gay,

All my thoughts are in a southern land.

Walking far into the sun,

Midst the wattle and the gum,

Fragrant odours seem so near at hand.

For the bush is calling me,

Far away across the deep blue sea,

There’s a longing in the beating of my heart.

In the world’s great lands I see,

Not a thing that might mean home to me,

While a gentle scent comes wafting from Australia.

There’s a tang of beach and shingle just as strong as can be,

There’s a little pal, an outdoor girl, waiting with my horse and dog for me.

As I dream most every night,

Of the sweetness of an Aussie twilight,

I can smell the scent from fair Australia.

Once more with the kangaroo, jackass and the old gum too,

I’ll be brighter than the wattle flower,

You’ll be waiting by the track, on the day that I’ll get back,

Home again to where those big trees tower.

For the bush is calling me,

Far away across the deep blue sea,

There’s a longing in the beating of my heart.

In the world’s great lands I see,

Not a thing that might mean home to me,

While a gentle scent comes wafting from Australia.

There’s a tang of beach and shingle just as strong as can be,

There’s a little pal, an outdoor girl, waiting with my horse and dog for me.

As I dream most every night,

Of the sweetness of an Aussie twilight,

I can smell the scent from fair Australia.

Updated