- Conflicts:

- Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) (1947-1951), UN Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (1948-1985), UN Commission on Korea (1950), Korean War (1950-53), UN Observer group in Lebanon (1958), Cyprus (1964-2017), India-Pakistan Observation Mission (1965-1966), Rhodesia (1979-1980), Namibia (1989-90), Cambodia (1991-93)

- Service:

- Peacekeeping operations

by Ian Jackson

‘Peacekeeping is not a soldier’s job, but only a soldier can do it.’

Dag Hammerskjöld, former Secretary-General of the United Nations

As the combatants in the First World War (1914–18) discovered, it is easier to start a war than to end one. When that war started in August 1914, victory was expected by Christmas. But four years of grinding conflict followed. With every dead and wounded soldier on either side, bitterness and enmity grew. Peace initiatives failed, until Germany’s eventual military and political collapse caused it to seek an armistice on 11 November 1918. However, the end of the war did not bring permanent peace; the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 was prophetically described by Marshal Foch, the French high commander, as a ‘twenty-year truce’, and in 1939 war returned.

In 1945, at the end of the Second World War (1939–45), the victorious Allies formed the United Nations (UN), with a Charter committing it to:

save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind.

But how could this be done? The UN Charter created a Security Council with sweeping powers to resolve international disputes and respond to aggression, including through military action. When conflicts broke out in the late 1940s in the Middle East, Kashmir and Indonesia, ceasefires were brokered by the Security Council.

But ceasefires on paper needed maintaining on the ground if war was to be avoided. This is not a straightforward task. For example, participants in a conflict will often try to use the respite of a ceasefire to their advantage, regrouping their forces and consolidating gains before restarting fighting. This was the case in Indonesia’s civil war in 1947. A ceasefire between the Dutch colonial authorities and the Indonesian independence movement was imposed by the UN Security Council, but Australian diplomats believed that the Dutch were using the ceasefire to improve their position, quietly neutralising pockets of Indonesian resistance behind the ceasefire line.

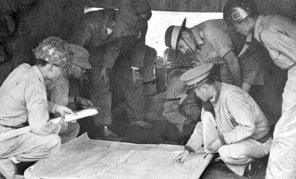

In response, a UN Consular Commission agreed that 24 military officers should observe both sides of the conflict, providing experienced but independent military ‘eyes on the ground’ to report on what was going on. The first to arrive, on 13 September 1947, were four Australian observers, becoming arguably the first UN peacekeepers in history.

The UN peacekeepers in Indonesia worked out a set of principles that have held for observation missions ever since. They decided that observers should regularly cross between both sides of the ceasefire line, operating in mixed nationality teams. This helped demonstrate their neutrality, and the cardinal principle that they were there as representatives of the UN, not their own countries or either side of the conflict. They would issue no orders, but would use persuasion and communication to resolve disputes.

Soon after, military observers were also sent by the UN to monitor ceasefires after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and following the 1947–48 war between India and Pakistan in Kashmir. Gradually a new form of military activity, peacekeeping, emerged.

The ceasefires in these conflicts endured for decades. Australia has contributed personnel to the UN Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) in the Middle East continually since 1956. An Australian, Lieutenant General Robert Nimmo, commanded the peacekeeping operation in Kashmir from 1950 until 1966, a length of service unique in UN history. In Cyprus, Australia provided police officers to keep the peace between Turkish and Greek Cypriots for 53 years, ending only in June 2017, with no solution to the division of the island in sight.

Another long-running UN military observer mission has been in Korea. When tensions between North and South Korea increased in early 1950, the UN sent two military observers, Australians Major Stuart Peach and Squadron Leader Robert Rankin. They observed South Korean operations along the 38th Parallel which formed the border between North and South Korea, and wrote a report assessing that they were purely defensive in nature, with no signs of preparation for an attack. Two days later North Korea invaded the South, and Peach and Rankin’s report was used by the Security Council as evidence that North Korea started the Korean War. UN observers remain in Korea to this day, monitoring the 1953 armistice, which remains in force as the participants in the war have been unable to agree terms for a permanent peace treaty.

Peach and Rankin’s experience shows that military observers cannot directly stop conflict breaking out, but they can assign blame and act as honest brokers. When John Burgess arrived in Kashmir to serve as a UN observer, Lieutenant General Nimmo told him:

Well you won’t be carrying weapons. All you will have to protect you will be a white flag or a blue flag. I expect you to try and stop the shooting. If firing breaks out you will have to stop it some way. I will leave it up to you to decide how to do it, but do try not to get killed. It is embarrassing if you get killed.

Observers were expected to negotiate to stop firing across the ceasefire line; if necessary, crossing no-mans-land to meet with the opposing forces or to confer with observers on the other side of the line. If it was impossible to stop the fighting, observers would count casualties and meet with the commanders afterwards to try to stop it happening again.

Negotiation and unarmed observation could prove highly effective in stopping conflicts escalating. Burgess recalled a time in Kashmir when fighting nearly broke out over a disputed cemetery:

There was a confrontation on the border... the Pakistanis brought up artillery and armour and infantry and the Indians had the same on their side... And they were so close together they were rolling grenades across at each other. And it was at that area that our two people were wounded, they were both wounded by a grenade explosion.

At that stage General Nimmo came up and bought into it and he really gave both of the commanders a hammering and even though he was shorter than them he stood up with his finger in their chests and told them to, ‘Back off and get out of it.

Real courage is needed to be effective in such dangerous situations. Major Roy Skinner served with UNTSO in the Middle East during the Six Days War of 1967. He travelled to the town of Kantara, on the Suez Canal, which had been captured by the Israelis and was under Egyptian attack. He wanted the Egyptians to know that the UN had arrived in the town, so he stood on the bank of the canal, wearing his blue beret, and shouted to the Israelis to stop firing. They did so, the Egyptian attack stopped, and the ceasefire took hold.

Even when fighting does not break out, landmines are a serious threat both to observers and to local people. Moreover, a military observer’s courage must be tempered by patience and self-discipline. Both sides in a conflict may try to deliberately provoke peacekeepers into becoming embroiled in their disputes. Avoiding this means not just staying independent but taking great care to be seen to be impartial, for example through carefully documenting events as they happen. Lieutenant Colonel Paul Symon was commander of the Australian contingent in UNTSO in 1997, at a time when Israel was fighting a proxy war against Hezbollah in southern Lebanon. He later wrote:

In Lebanon, I learnt how terribly elastic truth in conflict can be, reinforcing the need for objective reporting.

Tact and cultural sensitivity is also vital. When Rhodesia was in the process of becoming the independent nation of Zimbabwe, an Australian peacekeeper, Major Kevin Byrne became commander of a cantonment where guerrilla fighters of Robert Mugabe’s Patriotic Front were assembled. He sought to get them to engage with the white local population, even arranging a cricket match between the Patriotic Front and local farmers: sport representing a common ground that could unite both sides of the conflict, and the Australian peacekeepers as well.

Such confidence-building measures became more important from the 1980s onwards. Australians served in a series of peacekeeping operations where the task of monitoring a ceasefire was supplemented with efforts intended to build the capacity for peace and reconciliation within a war-torn society. rather than simply freezing a conflict in place, these operations aimed to build trust between warring parties and enable a political transition. In Rhodesia (1979–80), Namibia (1989–90) and Cambodia (1992–93), this meant providing an environment stable enough for elections to be held.

When the Australian engineers of 17 Construction Squadron arrived in Namibia in 1989, the ceasefire between the colonial South African government and African nationalist rebels was breaking down. The Australians established assembly zones for the rebels. Despite intimidation by the South Africans aimed at forcing them to hand the rebels over, they re-established the ceasefire and enabled the peace process to continue. The engineers then constructed police stations and polling booths and built an airstrip. Elections were followed by Namibian independence and the end of the conflict.

Similarly, in Cambodia, an Australian, Lieutenant General John Sanderson, commanded a multinational UN peacekeeping operation to maintain the ceasefire in that country’s long-running civil war and, it was hoped, supervise the separation, disarmament and demobilisation of the different forces, allowing the return of refugees and the organisation of elections. Cambodia had almost no communications infrastructure; the Army signallers who formed Australia’s main contribution to the peacekeeping force had to establish a communications system across the country. This enabled Sanderson to mould a cohesive peacekeeping force from the 34 nations contributing troops. Although disarmament proved impossible, the ceasefire held, and the 1994 elections were a success.

The Australian armed forces’ attitudes towards peacekeeping have changed since the 1950s and 1960s, when peacekeeping was sometimes seen by military commanders as a distraction from fighting in, and training for, wars. reliance on non-violent intervention was seen as the opposite of true military practice and not relevant to service in war. But peacekeeping is now seen as an integral part of the Australian Defence Force’s purpose.

This partly came from a realisation that there were valuable military skills to be learnt from peacekeeping. The personal qualities of courage, self-control and cultural sensitivity required from military observers make for good soldiering in the modern world. Learning how to work with other countries’ armed forces is essential given Australia’s dependence on alliance with other powers for its own defence. And the counter-insurgency operations that typify modern warfare can have much in common with peacekeeping operations. For example, Paul Symon observed close-hand guerrilla tactics used by Hezbollah in Lebanon, that he later encountered being used against Australian forces by enemy militia in Iraq.

Australians continue to monitor both long-established and new ceasefires around the world: from the long-running operations in the Middle East to the world’s newest nation, South Sudan. In Sudan, as in all modern conflicts, peacemaking is a process and not a one-off event. Progress can be achingly slow, but peacekeepers, through observation, engagement, negotiation and simply being present, can make sure the hope of peace gets its best chance to stay alive.

Updated