- Conflict:

- First World War (1914-18)

In recent years, a new field of research has gradually come to the forefront among specialists of the First World War: the Great War’s place in the 20th century and its impact on forms of violence after the war. In the tradition of George Mosse, some historians stress the process of ‘brutalisation’ that occurred after the war, although it is not clear whether this phenomenon mainly affects post-war societies and their political life, or former combatants as individuals, or whether it affects all countries in similar ways.

The transfer of wartime violence to the post-war period is in fact a complex mechanism and the terms ‘violence’ or ‘forms of violence’ are used to designate very different realities: battles between regular armies, for example, the Greco-Turkish War; ideological struggles against an ‘inner enemy’, as in the case of the Russian civil war; liquidation of the war’s legacy, such as the purge of collaborators in Belgium; violence perpetrated by paramilitary groups, as seen in the counter-revolutionary repression in Germany; acts of ethnic or community violence, as in Poland and Ireland.

The specificity of these conflicts depended somewhat heavily on the experience of individual nations in the First World War (conquest, invasion or occupation? Victory or defeat?), the ability of the state to channel or redirect the violence deployed during the war and the nation’s place on the world stage. A resurgence of violence in the colonies thus characterises the post-war period, particularly in India, Egypt and Iraq in the case of the British, and in Algeria and Indochina in the case of France.

Several factors, sometimes working in concert, explain the violence of the post-war period, namely, the repercussions of the Russian Revolution in 1917 in Russia and other countries, and the frustrations born of defeat. In addition, national or ethnic tensions inherited from the disintegration of the four great empires (German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman), could take various forms: territorial claims, border tensions, populations on the move. In this extremely diverse and complicated climate, a clear delineation of any continuity between the ‘cultures of war’ in 1914–18 and post-war violence is therefore far from straightforward.

Different approaches are often necessary: studies of local circumstances, the progress of veterans and veterans’ groups, civilians who refused to move on from the war, the possible reuse of tactics and weapons first used on the battlefields and then in the 1920s, the gestures and language of violence, the ideological legacy of myths born during the war—for example, the ‘myth of the War Experience’ (George Mosse), the central element of the völkisch ideology in Germany or Italian fascism. The Arditi in Italy, the Freikorps in Germany and the Black and Tans in Ireland, all were veterans of the First World War, while Béla Kun’s Republic of Councils in Hungary (March–July 1919) was based on former prisoners of war returning from captivity in Russia.

I will attempt a brief typology of post-war violence here. Certain forms of violence were a direct consequence of whether a country had been victorious or defeated in the war, and related to the implementation of the Armistice conventions. The year 1919 saw the liberation of countries occupied during the Great War and the occupation of the Rhineland by the victors, which gave rise in both cases to violence against individuals and property.

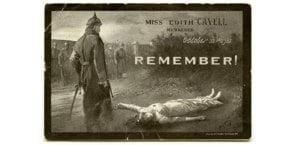

Belgium witnessed the hunting down of collaborators, particularly war profiteers and ‘shirkers’. In the spring of 1919, the Coppées, father and son, major employers in Hainaut, were accused of enriching themselves by supplying coal to the Germans. Their trial inflamed Belgian public opinion, which considered that the law was not dealing severely enough with collaborators. A similar emotion greeted the acquittal of several informers, especially Gaston Quien, brought to trial in 1919 for having betrayed Edith Cavell. In countries deeply divided by the war, as with the Flemings and Walloons in Belgium in 1914–18, the immediate post-war period was a time for settling accounts with wartime enemies.

In Alsace, civilians of German descent were expelled to Germany in the winter of 1918–19, even if they no longer had any ties with that country. In the Rhineland, occupying troops were known to play out, on a smaller scale, the confrontations of the First World War: brawls with German civilians, destruction of the 1870 war memorial at Ems, insults and humiliations for the Rhineland population.

In other cases it was the collapse of the structure of the state, combined with material chaos, which lay behind the explosions of violence. In many countries, the end of the war brought with it a collective traumatic shock, and a reformulation of the ‘culture of war’ into the struggles between counter-revolutionary and revolutionary movements.

In Italy, the rise to power of the Arditi and the fascist movement can broadly be explained by the moral collapse of military and political elites during the Great War: the nation was victorious, but the victory was incomplete and ambiguous, insufficiently convincing to wipe out the humiliation of Caporetto.

The position of Germany was distinctive because here defeat was attributed to treason, which facilitated the transformation of foreign war into civil war. In Berlin, 1919 opened with the Spartakist insurrection (5–11 January) and the particularly brutal assassination of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht by members of the Freikorps on 15 January. For several weeks the streets of the German capital were awash with the violence of war. A Berliner recorded in his diary that:

The combat... began near the colonnade of the Belleallianceplatz, then spread out against the snipers hidden on rooftops, before reaching the strongly barricaded headquarters of the newspaper Vorwärts, with its network of interior courtyards. People were using large-calibre bombs and flame-throwers. The doors were blown open by hand grenades and the defenders surrendered only on the approach of assault troops. Three hundred prisoners were captured and one hundred machine guns seized.

The German state no longer held a monopoly on legitimate violence. Its army had been largely dismantled since the defeat. To deal with the revolutionary threat, it depended on recently demobilised veterans, on groups of students too young to have fought in the war but keen to use their strength in the struggle against the ‘Reds’ and on local militias, who called for the destruction of the ‘Bolshevik vermin’. Everything seemed to favour a radicalisation of political violence: the eschatological anguish aroused by the defeat, the fear of contamination by communists or Jews, the hope that the fraternity of soldiers in the trenches could be recreated against a common enemy. ‘People told us that the war was over. That made us laugh. We ourselves are the war’, declared a Freikorps volunteer.

In this climate, the government of the Weimar Republic renounced its pursuit of those guilty of the double crime of the Spartakist leaders. At the funerals of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, nearly 300,000 activists shouted their anger against the Social Democratic government. The Freikorps, officially dissolved on 6 March 1919, proceeded two months later to crush the Munich ‘Republic of Councils’ in a bloody repression that resulted in 650 deaths. On the eastern margins of Germany, the Bolshevik threat was equally present, and the Freikorps were used to counter the risk of revolutionary expansion.

In Russia, the weakening of state power also opened the way for warlords to take control, with their private armies pillaging, terrorising the population and conducting repeated pogroms, such as in Ukraine. The Allied intervention on the side of the White armies, in the context of the civil war, further contributed to the radicalisation of the violence of war. Faced with the intervention of a foreign force, which numbered nearly 20,000 men in 1919, and with the pressures of ‘internal enemies’ (White partisans of the armies of Kolchak, Denikin or Wrangel; kulaks, i.e., prosperous peasants, and ethnic minorities), the Bolshevik regime sensed that it was fighting for its survival.

In this particular period of ‘War Communism’ (1918–21), political splits between communists and (real or supposed) counter-revolutionary opponents, currents of social antagonism between urban and rural societies and ethnic struggles and national confrontations all came together to sustain a climate of permanent and varied violence. One such war, between Russia and Poland in 1919–21, left 250,000 dead. In a speech at Rostov-on-Don in November 1919, the philosopher Piotr Struve, a former Bolshevik who rallied to the White movement, stated that:

The world war ended formally with the conclusion of the armistice... In fact, however, everything that we have experienced from that point onward, and continue to experience, is a continuation and a transformation of the world war.

During the so-called ‘peasant wars’ that broke out over the requisitions of grain crops, the special forces of the Cheka, the political police, used extreme brutality to crush rebellious peasants. Civilians massacred, villages shelled, the use of mustard gas—all demonstrate the full extent to which the practices of war inherited from the Great War were used on the home front, along with a radicalised perception of the enemy within.

The fourth and final element in post-war violence was ethnic. The collapse of the Russian Empire first brought a surge in nationalist tensions in the Caucasus, in the new Baltic states and in Poland. These tensions tended to concentrate in smaller territories that carried symbolic weight, such as the city of Vilnius, disputed by Poland and Lithuania, or the port city of Memel, which the Treaty of Versailles put under the control of an Allied commission. Poland and Lithuania both claimed Memel, and Lithuania eventually took over the city in January 1923.

The city of Fiume was another example of territorial struggle. Accorded to the Croats under the Treaty of London on 26 April 1915, Italy subsequently staked a claim to Fiume during negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference, citing the presence of the city’s sizeable Italian community. On 12 September 1919 the nationalist poet Gabriele D’Annunzio occupied Fiume illegally with a volunteer army, and for more than a year he headed a provisional government that favoured returning the city to Italian control.

In 1919–20, signatories of the peace treaties aimed to limit the risks of war by redistributing population groups, in the interests of building better ethnic homogeneity. However, the complexity of the intermingling languages, ethnicities and cultures, particularly in Central Europe and the Balkans, meant that things remained extremely confusing. In addition, the peace treaties set up clauses for the protection of minorities, which were guaranteed by the League of Nations. Furthermore, the treaties required each individual to settle in the country whose nationality he had adopted. In total, around 10 million people left territories that had passed into the hands of a third nation.

The Greco-Turkish war which broke out in May 1919, culminated in the capture of Smyrna by Kemalist troops, the burning of Armenian and Christian neighbourhoods and the massacre of nearly 30,000 civilians in September 1922. The forced transfer of populations between Greece and Turkey, undertaken under the auspices of the League of Nations in 1923, was the most dramatic consequence of the ethnic violence that broke out in the immediate post-war period, because it legalised an ethnicised definition of territory.

In this context as well, paramilitary groups appeared; they were responsible for much of the post-war violence. The distinctions between civilians and combatants, already vague during the First World War, completely vanished in this type of conflict. The Irish Civil War provides a good example of this: both the insurrection of 1919 against the British and the counter-insurrection were led by small groups that did not limit their targets to other armed combatants. The wives and families of militants fighting for independence were considered equally valid targets. British soldiers, supported by the Black and Tans, committed numerous atrocities against civilians. Conversely, the IRA conducted a policy of intimidation and revenge against those whom it saw as traitors. The bodies of those it executed were frequently left in a public place with the message: ‘Spy. By Order of the IRA. Take Warning.’

In the end, in Ireland, the Civil War produced much heavier losses than the First World War. Several factors were at work here: the lack of compunction on the part of paramilitary troops, who attacked civilians more readily than regular troops might have done; the power of identity stakes in a war that radicalised positions on both sides; and surely the brutalisation that the Great War seems to have brought in its wake to the Europe of the 1920s.

The year 1919 did not mark the end of the cycle that began in 1914, nor, indeed, did it illustrate any shifts in the violence of war. In many countries the already strong tensions produced by the war seemed to expand in the immediate post-war period, at the very moment when the diplomats from all over the world were gathering together in Paris to negotiate the cessation of hostilities. In the ruins of four empires destroyed by the Great War, nationalism expanded.

Revolutionary fever spread across Central Europe, stirring counter-revolutionary movements of equal violence. Sometimes, the First World War simply continued. Armies and combat tactics that had been tested on the battlefields beginning in 1914 were transferred to the context of domestic warfare and used against civilians. Sometimes, various states of conflict coalesced. In the case of Russia, for example, four different kinds of wars interconnected and fuelled one another: the war against Poland; the war of the Bolshevik powers against the White armies and their Western allies; the class war against the kulaks; and the repression of ethnic minorities by the central powers in Moscow.

Was 1919 the year of peace or the year of an impossible transition from war to peace?

The article above is an extract from Bruno Cabanes’s chapter ‘1919: Aftermath’ in The Cambridge History of the First World War edited by Jay Winter, published by Cambridge University Press in 2014.

Author:

Professor Bruno Cabanes is the Donald G & Mary A Dunn Chair in Modern Military History at the Ohio State University. He studied history at the Ecole normale supérieure, in Paris, and received his PhD, with distinction, from the Université Paris I- Panthéon Sorbonne. He taught for nine years at Yale University.

Professor Cabanes is a historian of 20th century Europe, and more specifically, the social and cultural history of war and is particularly interested in the period of transition that followed the First World War.

Updated