- Conflict:

- Afghanistan (2001-21)

When the Taliban entered Kabul on the evening of 15 August 2021, Western troops and embassy staff scrambled to flee a country of which its government had lost control. To the world, Kabul in August looked like Saigon in 1975.

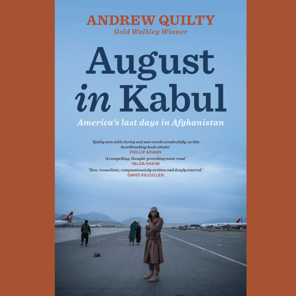

Andrew Quilty was one of a handful of Western journalists who stayed as the city fell. His book, August in Kabul: America's last days in Afghanistan is a first-hand account of those dramatic final days told through the eyes of Afghans whose lives have been turned upside down.

In September 2022, Andrew sat down in front of a live audience at the Shrine of Remembrance to discuss his book with journalist Tracey Curro. Listen as Andrew reveals what life was like in Kabul and shares stories from the weeks and months after it fell.

To purchase a copy of August in Kabul click here.

Credits

Speakers: Andrew Quilty and Tracey Curro

Music: Remembering Well written and performed by Stephen Keech

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: Hello and welcome to the Shrine of Remembrance podcast. My name is Laura Thomas, and I’m the production coordinator here at the Shrine.

The Shrine of Remembrance acknowledges the Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we honour Australian service men and women; and we pay our respects to Elders, past, present and emerging.

In this episode of the podcast, we’re looking back to August 2021, when the Taliban entered Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, after a 20-year conflict with the United States, its Western allies and a proxy Afghan government.

This forms the basis of photojournalist and Walkley-award winner Andrew Quilty’s new book ‘August in Kabul’. Andrew was one of a handful of Western journalists who stayed as the city fell, and his book offers a remarkable record of this historic moment told through the eyes of Afghans.

In September 2022, Andrew Quilty sat down in front of a live audience to unpack his book with Tracey Curro, who many will know as a former 60 Minutes reporter. Tracey is also an Al Gore Climate Change Ambassador, Queensland University of Technology Outstanding Alumnus and Shrine of Remembrance Trustee with more than 20 years experience as a journalist, producer and presenter in mainstream media.

Listen on as they discuss Andrew’s new book, and life in Kabul.

TRACEY CURRO: Andrew, as Dean said, you first went to Kabul in 2013. And I will take you back to the beginning in just a moment. But I want to start with your flight back to Kabul, from France, where you'd been for a friend's wedding. I'm not sure how long you'd been out of the country. But what was it that compelled you to return to Kabul at what was, I think, perhaps the most dangerous time to be going back to that city?

ANDREW QUILTY: I think it was twofold. First of all, I, I suppose I had a- some sense of responsibility as a journalist, and as a photographer. I'd been living in Kabul and travelling around Afghanistan for about eight years at that point, and, and this was going to be by far the biggest news story in that time, probably the biggest news story since the US invasion in 2001. And so I certainly felt a need to be there for that reason. But even more than that, I felt as though I just needed to be around my- the people from my community there, my friends, you know, those closest to me, my housemates at home, the dog that I looked after at home and a couple of staff members at my house, as well as friends, other foreign journalists and, and a lot of Afghan friends and colleagues, obviously, who I just I thought being estranged from them at that point would be something that I couldn't reconcile if I didn't go and certainly in the down the track in the future.

TRACEY CURRO: How compelling was the professional drive though? That sort of sense that there was, you know, that this was a moment in history that you wanted to be part of, and, you know, I guess there's a bit of sort of, perhaps, personal, or professional ego as well as professional obligation and wanting to be there.

ANDREW QUILTY: Actually, that wasn't, I mean, that was very much supplementary. And it wasn't, I took no delight whatsoever in going back. I mean, it was, it was a horrible time, and leaving Paris, to fly in I was, I was I didn't have a good feeling about what was what was to happen. And when I, when I got home to Kabul that night, and I, I caught up with a few friends, and we, you know, talked about what was happening and what we were expecting for the days to come. I mean, we were all in tears. It was awful. This was the end of this city of our home, as we've known it, and it was, it was going to be a place from which our, our friends and our colleagues would be the very next day running for their lives from.

TRACEY CURRO: So grief, loss, a sense of what hopelessness or helplessness, was there fear as well?

ANDREW QUILTY: Yeah, there was definitely fear. We didn't really know at that point how it was going to happen, whether it was- whether the government was going to put up a defence of the city, in which case, you know, we expected it to be a return to the Civil War of the 1990s. And, you know, at which point it would be cross your fingers and hope to survive. Because at that point, the airport would have closed, the city would have been besieged, there would have been no way out, it would have been just a matter of riding it out until the Taliban inevitably won because they were always going to win. Or, as it turned out, the, at this point, what I hoped for, despite what a a Taliban-led, Afghan government would mean for the future, I hoped that the Afghan, the republican government, would hand over the keys to the palace, basically, because it was, as I said, the Taliban were going to win one way or another. They could hand over the keys and let them do it peacefully or they could put up the fence and you know, tens of thousands of people would have been killed.

TRACEY CURRO: So take us back there. Give us a feeling for the city that night that flew back in the next morning, you know, as the sun rose.

ANDREW QUILTY: Arriving back in Kabul, I mean, leaving the airport to get to my home, we sort of took a long route to drive around the city because there was quite a bit of commotion in the city. A lot of people had come in from the outlying provinces ahead of the Taliban's advance, and were camping out in parks and public spaces in the city, there were huge queues outside banks, people trying to withdraw their savings. But other than that, life was going on. That changed a little bit the next morning. Those crowds outside the banks got more anxious and grew. And the security guards who were manning those, those banks, the entrances to the banks were, you know, getting very nervous and finding it very difficult to control the city. A lot of the members of the Security Forces, the police and the army, we found out later were turning up to work that day with civilian clothes under their uniforms. As it turned out, in anticipation of the moment where they had to strip off and blend into the community so they weren't, they didn't stand out to the Taliban.

TRACEY CURRO: And so what did you do on that first stage? Is it slinging a camera around your neck, grab your mobile phone and head out to see what you can find or?

ANDREW QUILTY: Oh, first of all, me and my friends that were staying at my house at the time, we didn't sleep much the night before, we were up all night trying to book contingency flights out of the country, just to have them. We didn't know whether we would actually use them yet. But I booked two flights over the course of the next week, just to have in my back pocket in case I needed them. And then it was just a matter of sort of keeping up with what was happening, you know, where the Taliban were, how close they were to Kabul and, you know, probably went to sleep around three or four and then woke up pretty early the next morning. And one of the first things I did was with a friend, I went to get a COVID PCR test to get the flight the next day, you know, it was a bizarre thing to do under the circumstances. But to get on a flight, you still need a PCR test and a negative PCR test. And, it was when the friend and I were walking back home from the medical clinic that we heard some distant gunfire and people running down the street, running towards us, cars turning around in the middle of the street and heading away from the city. And that was the moment that the similar things were happening all around the city and, and everyone, you know, asking people what's happening and people saying 'the Taliban's here, the Taliban's here, so we started sort of running back towards home. And it turned out those gunshots were security guards outside the banks trying to control the crowds. But it was that moment that that caused all the members of the security forces to start stripping off their uniforms, and fleeing their checkpoints abandoning their vehicles, leaving them in the middle of the road with keys left in ignition. And precipitated the collapse of the entire you know, tens of thousands of members of the Security Forces in Kabul. And then within a few hours, there was almost no, no one defending Kabul. And the Taliban who by this point were had encircled Kabul, and were waiting outside for orders as to what to do from their commanders n who are in Doha at this point or still in Pakistan, waiting for orders. And it wasn't until maybe I'm getting ahead of myself.

TRACEY CURRO: Finish your train of thought

ANDREW QUILTY: Well, it wasn't until a few hours later by which time there was a complete security vacuum in Kabul and looting had begun and, you know, people are entering police stations and government offices and you know, running out of computers and safes and equipment, you know, weapons and vehicles and everything that the Americans and the Americans who are still in Kabul, and the Taliban leadership in Doha were in communication. And they were basically arguing over whose responsibility it was to maintain security of Kabul. So the Taliban told the commander of all US Forces who was in Kabul, you know, 'You've got to send your men out to secure Kabul or it's going to be a you know, bloodbath', or a free for all, you know, looting and raping and murder and things and, you know, bizarre circumstances where you've got the Taliban asking, requesting the Americans to secure and the American commander said, 'My order is to secure the airport and that's all so it's over to you' and at that point, the leadership in Doha told the commander's surrounding Kabul to enter Kabul and secure it.

TRACEY CURRO: I want to juxtapose that sort of sense of chaos. And I know you make the point at the, in the book that, you know, as a journalist, this story is not about you, but I want to juxtapose that, that chaos with, you know, a young Aussie bloke who, you know, grows up in Mosman, goes to private school

ANDREW QUILTY: You didn't have to mention that

TRACEY CURRO: St. Aloysius, you know, studies photography, gets a job at the Australian Financial Review. How do you find yourself in Afghanistan? And what sort of drew you there? Was it just curiosity? And what compelled you to stay for so many years?

ANDREW QUILTY: I mean, I'm not much of a planner. So I never certainly never plan to stay as long as I did and I first, the first time I made attempts to go to Afghanistan was with my cousin, Ben, who some of you will know his painting. So he went to Afghanistan in 2011, I think as a guest of the Australian War Memorial. And so I, I tried to, I wanted to go with him to document his work there. I thought I thought it'd be a, you know, sort of easy entry point, to a difficult environment. And that never happened. But I guess it, it had piqued my interest. And then in late 2013, I was living in New York at the time and a friend of mine that I worked with, back in Sydney, asked me if I knew any photographers in Afghanistan and Iraq, where she was planning to go to write some stories on spec for Australian publications. And without really thinking of it, I said 'Well, I'll come'. And so we went to Lebanon. And then we went to Afghanistan, we were meant to spend two weeks in Afghanistan photographing, I was going to photograph the Afghan cricket team that was about to go to Australia for their first World Cup tournament. And we, I mean, the Afghan bureaucracy and processes in general are pretty time consuming. So we ended up you know, we needed more time there. And so we extended, you know, to a month and then two months, and then three months. Also because we're just enjoying yourselves, we were making some friends. And we went beyond the initial story we wanted to do, and we travelled around a bit. And by the end of that three months, I'd fallen in love with the place. And so our three month visas expired. And so we had to leave but I went back to New York, packed up my things and basically moved to Kabul.

TRACEY CURRO: So when you say you fell in love with the place, what captured your heart? What was it that captivated you, because, you know, the sort of perception that one gets simply from watching TV news, is it you know, it's not the kindest place to raise family or

ANDREW QUILTY: Yeah I didn't go there to raise a family though. I mean, it's also, you know, what you see on the news is, is a very small proportion of what happens in Kabul. And, you know, it's not to say it's not happening, it is, but the other 99 per cent is not, you know, newsworthy, so you don't see it. And so,

TRACEY CURRO: Did you live a kind of normal life?

ANDREW QUILTY: Yeah. It was Kabul normal. Yeah.

TRACEY CURRO: Not Mosman normal.

ANDREW QUILTY: But, yeah, I mean, I didn't consider myself having to make massive sacrifices in the, at the time. And, I mean, how did I fall in love with it. I mean, you know, I guess love can be hard to define, in any manifestation, but it was there as well. But, you know, there's a number of things I, for one, I, I became part of a community of, I guess, like minded people that were, regardless of their age were at a similar time in their life. They didn't maybe have the kind of responsibilities that my contemporaries back home had, they were, you know, focused on their work. They were passionate and hardworking and I suppose you know how to you know, there's one way I heard used to describe the kinds of people that end up in Kabul, misfits, mercenaries. And one other thing.

TRACEY CURRO: I don't know but you're making me think of Darwin.

ANDREW QUILTY: Missionaries, missionaries. So I don't know which one I fit into. But it was also, I mean, as a photographer, it was, I mean, just on a superficial level, it's a spectacular country, and Kabul hemmed in by five 6000 metre mountains that are snow capped almost all year round. And there's always dust in the air and there's, in winte the smoke from wood burning fires and coal and and there's a there's a lot less visual interruptions on the streets in Kabul, you know, there's not that much advertising, there's, you know, streetlights and these kinds of things, which are also obviously, that's because of the lack of development there. So it's, you know, it's a, it's a bit of a you know, have sort of difficulty reconciling that but, you know, because it's, it's hard not to, I mean, it becomes a little bit Orientalist to to kind of glorify or romanticise this, you know, developing country which is, you know, in more realistic terms, just dirt poor and, and wanting for a lot. But also the people and the way people, the way Afghans respond to a camera is very different to the way we do here

TRACEY CURRO: How so?

ANDREW QUILTY: Here, someone points a camera at you, you instinctively smile or, or...

TRACEY CURRO: Pout

ANDREW QUILTY: I think it's called duck face these days. And not only that, but the, the hospitality and the warmth of the people there is, I found it very surprising, because I just thought they must hate all foreigners, for everything that we've done over there over the years, you know, just caused so much strife from hundreds of years back, despite, you know, well meaning intentions at times.

TRACEY CURRO: So you found you found friendships?

ANDREW QUILTY: Yeah, and not even, you know, the close friendships but just the I mean, I met up with an Afghan friend yesterday, who was evacuated last year and, and he was mortified when I wouldn't go back to his house in Dandenong for him to host me to dinner. I mean, that's the kind of, you can't you can't walk past an Afghan who's drinking tea out the front of his shop or house who won't invite you in for tea.

TRACEY CURRO: So you don't think of yourself as a war correspondent? How would you characterise your work?

ANDREW QUILTY: I was a photographer or photo journalist that worked in a country that was at war, I suppose. I guess that I can see why I got that. But, you know, one thing came before the other.

TRACEY CURRO: And so what's the in terms of how you kind of perceive your work? I mean, how does that come through in, you know, in the way that you've chosen to tell the stories, of August in Kabul? It seems to me that you've chosen to, you've chosen a number of people who you met, who in as you say, were sort of trying to live and work amidst conflict. And through their stories, you've actually been able to tell a kind of broader, I think, story of war.

ANDREW QUILTY: I suppose I wanted to choose a group of characters that would give a good cross-section of experiences of not only this, this time in Afghanistan, but the experience through their lives and through their parent' lives and culturally, socially, politically. You know, the circumstances that led to this point and how it shaped the way that they responded to this moment. And that goes from, you know, members of the Taliban who had grown up in, in rural parts of the country and been drawn to take up arms against the soldiers, they considered invaders and occupiers to those who grew up in favour of the republican government, which was, you know, often determined less by chosen political ideology, as much as it was chosen by, you know, where they were born or the ethnicity they were born into, you know, whether they were born in a rural area or urban area often determined where, you know, in the same way it does here. Yes, you know, that most of our I'm not so sure about here, but in the US, most of the military's recruits are from small towns or more rural areas, it's certainly not the, you know, the big coastal cities. In any event, it's the same there.

TRACEY CURRO: So let's talk a little bit about some of the people the characters in your book. And you start with a place called Antenna Post, so named after a mobile phone antenna. Tell us a little bit about Captain Solomon

ANDREW QUILTY: So he was one of these soldiers on the government side. And he was a young captain in the Afghan National Army. And he, as you do in Afghanistan, you rise up the ranks pretty quickly. Often through nothing more than survival. If you, you know, if you're alive, and often, you'll get a promotion. Yeah. And so he'd spent three years fighting in Helmand Province, which is in the south, and which is the most violent province in the country throughout the war. And he was, he was offered a promotion up in this, this province, on the edge of Kabul, which was significant, both because of its proximity to Kabul, and also the fact that the main arterial road that ran around Afghanistan, ran through this province. And he was, he was asked to lead the defence of a small area within this province, that was straddling an even smaller road. So he had he just control the four little outposts and about 30 men that were aiming just to keep this open. And, and he was flown in there in, I think, May last year, 2021. And, and he quickly realised what precarious situation he and his men were in, you know, basically, they were surrounded on all sides, they couldn't even go down to the, to the creek to fill up their water, they would, instead of doing that, they would fire their machine guns in front of passing motorists on the road to get them to stop, and then order them to come up the hill, take the jerry cans down, fill them up with water and take them back up.

TRACEY CURRO: That doesn't exactly win you the hearts. and minds of the citizens does it?

ANDREW QUILTY: Not at all. And so he started to try to develop relationships with the, with the local elders in the community. Who, you know, had lived through that they lived either side of this, this, this small road, which should, you know, it was always coming under attack from the Taliban, you know, attacking the Afghan Army convoys and these outposts and they were just sick of it, you know, all their animals would get shot that, you know, the apricot trees would die from shrapnel wounds. And you know and they would they often were killed or wounded themselves. And so this one man who became a bit of a broker, he was a local farmer and an elder in the community became a bit of a broker between Solomon and his Taliban counterpart who was trying to take over these checkpoints in order to cut access to to the district capital, which was a little bit further down.

TRACEY CURRO: So it was a fairly strategically significant site?

ANDREW QUILTY: It was, but in a very small, you know, Afghanistan is broken up into 34 provinces, and within the 34 provinces are about 400 districts. So this was the main road through one of the 400 districts. So it's like, you know, it's a, it's a backwater.

TRACEY CURRO: But was it a microcosm, do you think?

ANDREW QUILTY: Yeah, very much so

TRACEY CURRO: And, and I was reading that, you know, even getting supplies of food and water into Antenna Post was something that, you know, was difficult, if not impossible.

ANDREW QUILTY: Yeah. So in the end, the only way to get supplies in was to fly them in by helicopter, but so close were the Taliban that helicopters could only fly at night. And then even when they came in at night, they would come under fire and, and so it just became more and more precarious to the point that soldiers started to surrender to the Taliban. The Taliban were offering not only amnesty, but they were offering money to any Afghan soldiers who surrendered and even more money if they bought weapons with them. And as the situation at Antenna Post became more precarious, the motivation to take the money and the amnesty became greater and greater.

TRACEY CURRO: To an Australian serviceman or woman that the idea of you know, stripping, stripping your uniform, handing over your weapons, taking the money and kind of running is anathema. What do we need to understand within the Afghan context to, I don't know, empathise or, or at least, understand why someone in the Afghan defence force would do such a thing?

ANDREW QUILTY: Well, I don't know. Is it anathema? It's like, I mean, it's like the Alamo. I guess that's the classic historical example. But I mean, I don't know when the last, maybe in Vietnam, maybe the, I guess, like Khe Sanh, where there were Australian soldiers basically surrounded, but they also had the Australian and the American military behind them, and huge amounts of ordnance and air support and all these things.

TRACEY CURRO: I guess, do you think of that in a sort of formal context of surrender, rather than, you know, shedding and running?

ANDREW QUILTY: I guess, you know, they both amount to the same thing at the end of the day, but it got to the point for these guys that it was it was surrender or die, there was no, there was nothing else. And no other options. And I think they didn't have enough belief in the government that they were fighting for. I mean, first of all, they knew that, that they'd lost faith in the government, because the government wasn't giving them the support they needed. They, they, in the end, they were just too overstretched because, the Afghan military had relied so heavily on American military support for the whole war. And they've been built in the American military's model. But they were not built to work, to operate without it. And that means air support. That means, you know, supply chain support and logistics and all and maintenance of their, of their aircraft. I mean, as the American slightly withdrew from Afghanistan, they took the maintenance contractors with them who were maintaining the Afghan Air Forces fleet. And and, you know, by the end of August last year, the Afghan fleet was basically grounded because they weren't maintained. And so yeah, for all those reasons, I think in the end, they didn't have reason to keep fighting on and if the government wasn't going to support them, then why should they fight and die for them?

TRACEY CURRO: I imagined that it's not possible to be in the midst of that very complex conflict as a photojournalist for so many years without forming some fairly clear views about what the key mistakes on all sides were that brought us to the 30th of August.

ANDREW QUILTY: I think the first mistake, I think this is fairly uncontroversial was when Donald Rumsfeld, the US Secretary of Defence in 2001, denied the Taliban who still was still controlling a few cities in the south of Afghanistan. The US forces with the Afghan allies had taken Kabul and most of the rest of the country. And the Taliban leadership reached out to Hamid Karzai who had been installed as the interim leader of Afghanistan, and said, 'Okay, we want to be involved in the peace process. We will hand over these last cities without a fight. We just want to live in, we want to live in dignity'. And Karzai agreed to it. But when Donald Rumsfeld got wind of it, he said, 'We're not in the process of negotiating with terrorists, and we don't have enough troops on the ground to take prisoners. So forget it'. And that forced the remains of the Taliban leadership into Pakistan, aggrieved, and, you know, eventually, fermented the insurgency that ended up becoming the now government.

TRACEY CURRO: Is there a number two?

ANDREW QUILTY: There's 2 million more probably. But I mean, I think the whole counterinsurgency, the idea behind counterinsurgency was very, I mean, it's, I think on paper, it sounds great, but when it requires a very violent, very blunt tool of elite special forces going in and rounding up supposed members of the enemy, the Taliban, al Qaeda, whoever it is, and in the process collecting a lot of scalps that have nothing to do with the Taliban, and fermenting dissatisfaction and anger and resentment everything towards the government and the forces that are supporting them. I think they both undermine each other. And I think, I mean, I saw that time and time again. And, you know, our own forces were not immune from that.

TRACEY CURRO: How frequently did you come across Australian serving personnel?

ANDREW QUILTY: Very rarely. I was there in late 2013, by which time most Australian personnel were either out of the country or in Kabul in training roles. I would very occasionally see Australian Bushmaster, a convoy of Bushmasters driving through Kabul. And, I mean, even seeing that from the point of view of the, from a civilian point of view, where everyone would take a step back, the traffic would clear out from around them, because they were a target for suicide bombers. And they were invisible and fearsome. You know, if anyone's seen a Bushmaster, it's basically the tank on tires and, and it's very imposing and scary, and you can't see who's driving it, except for the mechanised machine gun out the top and, and that was the view that most Afghans had of the International Military there. And it's, you know, it's hard not to look upon them as occupiers from that point of view, you know, you when you can't even they just look like robots from this, from that point of view. And, and so is that strange dynamic, and this is even in Kabul, where a lot of people have the international military and they're the diplomats and development agencies to thank for, for a lot of what they've benefited from in the last 20 years. But on the other hand, they you know, the suspicious and of the military and kind of, it's like 'Oh yeah we kind of want you but you know, not in my backyard', kind of thing

TRACEY CURRO: Of all of the images that you've taken, I don't want to ask you if you have a favourite, but is there one that even for you is somehow unforgettable?

ANDREW QUILTY: There was one photo - we need to screen here - it's not in the book actually. But there was a photo I took of a mother and her young daughter at the grave of their father who had been killed while being operated on in a in a hospital run by Doctors Without Borders killed in a US airstrike which had mistaken the hospital for an enemy target. And I had gotten inside the hospital a week after it happened while the city was still kind of in flux between the Taliban and government control and come across the body of their father while he was still strapped to this operating table and I'd photographed this scene and then I wanted to try and find out who he was and eventually I found out his name and then tracked down his family and I mean first of all, I wanted to ask them if they wanted to see the photo to begin with. And second of all, how they would feel about me publishing it and they really wanted me to publish it.

TRACEY CURRO: Why? I know the photograph you're talking about and I can't imagine that if that were an Australian, I would think that the image would be almost unpublishable here. Why were they so wanting you to publish?

ANDREW QUILTY: I think for recognition, otherwise, no one would have known what happened to him. I think they did receive some compensation, probably in the order of maybe a couple of thousand US dollars, if they were lucky. But, you know, they would have just been a statistic, he would have just been a statistic, and I think some sort of recognition of, of what happened and also of his life and his death. And so, you know, I spent a bit of time with the family. And eventually, one day they were going to visit his grave, and I asked if I could come along, and this is one of those pretty awful situations as a photographer, where you really ask yourself, you know, do I belong here, you know, this is such a private moment, and, and so I, you know, I made my camera as quiet as I could, you know, turned off the shutter and did everything I could to be as discreet as possible and got as close as I felt was appropriate. And, and I took a few frames of this scene with this young girl just clawing at her father's grave and, and her mother trying to comfort her. And that's, that's one that's always stuck with me. And also, I think, probably because I have a relationship with that family.

TRACEY CURRO: So the photograph, ladies and gentlemen of the Father, if you do want to Google that later, is just Google 'the man on the operating table' and Andrew's name, and I haven't seen the photograph of the mother and daughter. But perhaps we can find that online as well. There must have been many times were you, you had to sort of stop and think given, you know, that you felt part of a community in Afghanistan, that I guess felt like your home. And yet you were working there as well, where you had to question 'Am I a part of this community? Or am I working and a professional in this moment?'

ANDREW QUILTY: Definitely last year in Kabul, and I think the fact that I that the war had mostly been going on outside of Kabul for the years leading up to that point, was part of the reason I was able to stay as long as I was and part of the reason my friends and colleagues were as well, because it was, you could come home at night or on the weekend or after a reporting trip of you know, going to the frontlines or, you know, seeing the consequences of the war, you could come home and have a dinner party with friends and, you know, sleep with a dog on the end of the bed and have drinks with friends and you know, have a picnic with friends on the weekend and

TRACEY CURRO: So you could compartmentalise it?

ANDREW QUILTY: Yeah, I suppose that's right. And yeah, I mean, it was there was a physical, there was a proximity factor where it was, you know, it was, to a degree out of sight out of mind, you could go to it when you needed to, but you didn't have to live in it all the time. It was only was quite rarely that the war impacted intimately in, in Kabul itself.

TRACEY CURRO: One of the exhibitions, from the Shrine that's currently touring regional Victoria is called Changed Forever. And it's the story of migrants who've resettled here from war torn countries, and and also the stories of veterans from recent conflicts. And one of the storytellers, Annette Hoolian is a trauma surgeon. So she'd been deployed in East Timor, she's done three tours to Afghanistan. And she talks in the exhibition about kind of reintegrating back into life in Australia. And I just want to read you a quote, she says, 'It was very challenging. A lot of people just had no idea what was going on over there. The vast numbers of people who've been injured. Here, they're fighting over car parks or getting really upset about things that really don't matter at all. That lack of a worldview in people that you're trying to live and work with, back here in Australia is really challenging'. Does that resonate with you?

ANDREW QUILTY: Yeah, of course. I mean, I've never had that, I mean, it's actually surprising how quickly you fall back into those patterns. And you know, you have to remind yourself and remember what you've come from but I think for me, it's a little bit more about finding an identity or a purpose outside of Afghanistan. That's what I've kind of found difficult. And, you know, finding out where I fit in with whom and doing what?

TRACEY CURRO: What's it been like, retelling the stories, whilst you've been on tour promoting the book? And the reason that I ask that is because some of the people in the Changed Forever exhibition do say that it's, it's actually cathartic. But not for everyone.

ANDREW QUILTY: Well, I mean, I haven't told too many of the stories that are in the book yet. But I suppose we talked a little bit about leading up to the time of the fall. I mean, leading up to the release of the book, I found it, I found it pretty difficult talking about it to people, even people that had, you know, all the time in the world, a generous listening ear, I, I got frustrated because I couldn't, I felt like I couldn't evoke the, you know, the full experience all the senses that, you know, were firing at the time in a, retelling it orally. And, I mean, most people actually just don't ask. So for that reason actually, I'm really glad the book is out, because I think it's probably the best, the best version of the story I can tell. So it's a bit of a relief, actually.

TRACEY CURRO: I was of course, really interested in Hamid Safi being a media advisor in the presidential palace . Tell us about him.

ANDREW QUILTY: He was a, he was like a press secretary in the presidential palace. And I'd met him early last year, when I'd gone to the palace one day to to photograph the president and, you know, photographing a president anywhere, it takes a lot of, you know, a lot of processes, and especially security and things so, we were in touch quite a bit. And I finally met him on the day I was photographing him, and he was a really nice guy and you know, spoke fluent English and dressed really snappily and, and is, you know, very professional, but also just very genial and personable. And we got on well, and we remained in touch after, after that day, and he'd actually come back to me and asked if I could come to the palace and teach their media team or give their media team some photography tips, and come embe with them for a couple of weeks. And I was kind of interested to do that kind of selfishly, more for the access it would give me the the palace than necessarily the my ability or what I could share with the audio visual team, and but you know, as things started to deteriorate, I just got too busy trying to keep up with what was going on in Afghanistan. And so that never happened. But I had remained in touch with him and after Kabul fell I checked in with him and make sure he was okay, and then ended up spending a lot of time with him. Yeah, hearing about his, his experience of it all and going blow by blow from the days that led up to the collapse to what happened when he fled the palace and what he and his family did.

TRACEY CURRO: And am I right in saying they know he and his family are now in the US?

ANDREW QUILTY: You'll have to buy the book

TRACEY CURRO: Sorry, should have done spoiler alert. And I really, although we're almost out of time, I really can't wrap things up without at least touching on the plight of women in Afghanistan. And of course, we heard as you were saying before a lot of conciliatory rhetoric as the Taliban were resuming power and control. Did you believe that rhetoric or had your experiences in the country up to that point in time given you a clear filter through which to interpret?

ANDREW QUILTY: I really wanted to believe it, desperately wanted to believe it, because it was inevitable what was going to happen, what was coming, but all my friends in Kabul especially just said, 'You wait, wait and see'.

TRACEY CURRO: They didn't buy it.

ANDREW QUILTY: They didn't buy it. I mean, the most striking instance of when I heard that was a couple of days after the Taliban took control in Kabul, me and a photographer colleague were detained for about 10 hours one day, and we were detained in this house whose occupants were still there but who were also through no choice of their own, hosting 30 Taliban members, including a senior figure and all his, his men, and they, there are a few times during the day where we were talking to the residents and they were in tears, and this is while they were, you know, going out of their way to make sure we were comfortable and bringing us tea and food and things and, you know, trying to reassure us that everything would be okay. But they would say 'You guys will be okay. But for us' - I remember his words. He said 'As soon as the world looks away, they'll come after us one by one'. And they were in several times that day. And yeah, sure enough, I mean, I don't think they haven't been doing it on a kind of industrial scale or anything. But they've, you know, they've been doing it slowly and carefully enough that it doesn't, you know, attract the, there's enough plausible deniability, you know, there's, it's happening here and there, but it's very, it's that fear is palpable amongst people, especially those who have worked with the government, or it was the security forces or the international forces.

TRACEY CURRO: And sadly, the world has largely looked away now. What's, what's your number one, I'm tempted to use learning as a noun, but what's your number one kind of, I don't know, lesson, take out from this whole experience, you know, if it's changed you or changed your thinking in any way. What's most potent?

ANDREW QUILTY: Well, it's not a positive one. That's, I mean, I think it's made me a little bit fatalistic, and, and this is more on an instinctive level than an intellectual one. You know, just seeing how the rug can so quickly get pulled out from underneath. It makes me really consider and question the future and decisions that will impact the future. And it's, you know, it's something that, you know, I don't think is rational, but which I want to try and unwind, but it's definitely had that sort of impact.

TRACEY CURRO: Well, certainly things that we should be talking about. Moreso than car parks and what have you. Brilliant to have your company tonight. Thanks very much for sharing all of that with us. And folks, Andrew is going to hang out for 10 minutes or so if you'd like an autographed copy of his wonderful book, August in Kabul

ANDREW QUILTY: Or an unautographed copy

Updated