- Conflict:

- First World War (1914-18)

by Professor Bruce Scates

An Anzac Centenary initiative by the National Archives of Australia has digitised the records of thousands of Australians who returned from the First World War. New battles faced those who survived service overseas as they, and their families, struggled to cope with horrific physical injuries and deep psychological trauma.

Most readers of Remembrance will have accessed First World War service records online. Since Anzac Day 2007, this vast archival deposit has been freely available on the National Archives of Australia (NAA) website.

Sometimes these records are rich, complex and moving. Although much of Series B2455 (First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1914-1920) was culled after the war, many files still retain desperate correspondence with families, their anguished testimony at odds with the formal language of officialdom. Loved ones struggled to come to terms with their loss, especially when men were posted as missing and no one knew what became of them.

A legion of those missing men was never recovered from the battlefield: sons, husbands, brothers, lovers, were swallowed up by the mud of Flanders and the Somme, vanished in the tangled scrub of Gallipoli, or were blasted to pieces by artillery. Occasionally these files allow us to glimpse grief at the most intimate level. Unable to bury the bodies of their dead, families fashioned private memorials of the personal belongings sent home to them. ‘One pipe, one wristwatch, three postcards, a bible’, these commonplace but precious things mattered more to some than monuments of stone and statues of soldiers.

There is no doubt the digitisation of Australia’s service records has fuelled the boom in Anzac memory we have all witnessed in recent years. At the touch of a keyboard, families can retrace the journey of the men and women of 1914–18. But like every archive series, B2445 is incomplete. First Australian Imperial Force service records tell us much about the men and women who marched off to war but very little of the story of those who returned. The survivor’s battle to adjust to civilian life continued long after the guns stopped firing.

Private Bertram Joseph Byrne’s service record has been freely available online for several years now. The Dossier is 22 pages long, some of them blank. A sparse administrative record, it tracks the bare essentials of war service: ‘Embarkation’ and ‘Arrival’, ‘marched in’, ‘marched out’ of Camp, ‘taken on strength’, ‘Absent without out leave’. The labourer from Grenfell New South Wales never rose above the rank of private. He forfeited two day’s pay for some minor misdemeanour and was hospitalised (often) for illness. Byrnes was also wounded twice in action. ‘Gun Shot Wound Thigh’ reads one entry—‘GSW Face’ another.

One gains little sense from this file of who Byrnes actually was. We learn he is married, a Catholic, 5 ft 5 in height, with light blue eyes, and fair complexion. But in those 22 pages his words seldom appear. A printed signature vows—at the beginning of Byrnes’ war—to ‘truly serve our Sovereign Lord the King.’ And over twenty years after returning home Byrnes drafts a letter to Victoria Barracks in Melbourne:

I wish to apply to you ... for Duplicate service medals .... As some years ago I had the misfortune of having been burnt out the fire destroying everything. And I would be grateful if I could receive the above bye Anzac day [spelling and punctuation as original].

Series B2445 yields little insight into the wound Byrnes suffered, how it shaped his post-war life and how it changed the lives of those around him. By all but a careful reader, ‘GSW face’ might be easily overlooked—or seen as just another badge of service.

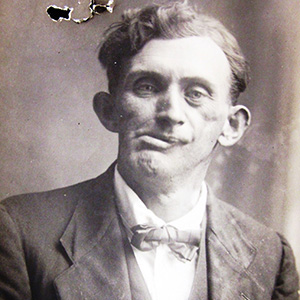

Byrnes’ repatriation records are much more substantial. It is one of thousands of case files awaiting digitisation. Australia’s post-war record, stored in National Archives deposits across the country, stretches across 10 kilometres of shelving. Three separate files span Byrnes’ wounding, hospitalisation and treatment. They chart his quest for an adequate pension, retrace his efforts to return to civilian life and bridge what has long been an historical hiatus between wartime service and post-war experience. They also show us what ‘GSW face’ really means. And show us quite literally. A series of photographs are appended to his clinical record. His palate and lower jaw have been shot away, most of his teeth are missing, a face that is bent and crumbled reveals the limitations of surgical procedures still in their infancy. Byrnes had been wounded less than a month before the war ended. The Repatriation file names the place: Péronne, a critical detail absent from the Service Record. The bullet entered at a right angle to his face and ‘came out under [his] left eye’, its passage ‘fractured’ much of his face and tore what was left of his jaw out of alignment.

The disfigurement was terrible enough. But Byrnes explained to his local member of parliament what a gunshot wound to the face actually did to him.

[Having] been shot through the jaws and lost my palate [and] an inch of my lower jaw bone I can only eat slop food and have to always take patent medicine to help digest ... my tongue has also slipped a considerable distance down my throat causing me difficulty to swallow.

There was a continuous discharge from his mouth as Byrnes was unable to control his spittle. Liquids forced down his throat came up again through his nose, and what one doctor called ‘an intractable foul discharge into his mouth’ caused bouts of indigestion, diarrhea and ‘feverishness’. Byrnes’ eyes were also affected by his war service, exposure to bright light led to severe headaches and partial blindness. Five years on from wounding and surgery, a doctor working for the ‘Repat’ declared Bertram Byrnes ‘Permanently and Totally Incapacitated’ (TPI).

It says much about the attitudes of the authorities that a case such as this was initially deemed suited to a life on the land. Despite his disabilities, Byrnes was considered hardworking and reliable, and that promised ‘good prospects of success’ wheat farming out at Wagga. Byrnes lasted on the block less than two years and only then with the help of his brother. He died in 1965, his wife and himself having eked out a living on ‘a ridiculously low pension’.

Files such as these make for confronting reading. Repatriation records chart the ordeal of the crippled, the blind, the gassed and insane—the ‘whispering men’ whose lungs slowly corroded, men with bullets or shrapnel working their way through damaged bodies, shell shock cases ‘eyes bulging with terror on any sharp or unusual sound’, men stricken with gastro, coughing up what meals they swallowed, malaria men, ‘feverish’, ‘shaking’ and ‘shivering’, ‘cot cases’ confined to bed for a lifetime. And reading these files one sees how war damaged more than just the soldiers who fought it—dreaming the ‘Germans were all around them’, nervy and violent men battered wives and children senseless. Brooding and self-pitying, many drank themselves to early deaths, abandoning responsibility for those dependent on them.

The men and women who returned to Australia were promised a land fit for heroes. But soldier settlers, like Bertram Byrnes, were often given marginal land instead. On inadequate, undersized blocks they faced poor seasons, bad prices and the onset of global depression. ‘I would sooner do 10 years of the war than one in the Mallee,’ one drought stricken farmer remarked. Many a veteran of Gallipoli, Belgium and France watched crops wither in the ground, or be eaten out by plagues of mice and rabbits, and saw the labour of a lifetime come to nothing.

It is a popular myth that soldier settlers were granted free land by a grateful government. Nothing could be further from the truth. Returned men and women took out loans, and were often crippled by a regime of impossible repayments. Every year on the land they sank deeper into debt. Ashamed by their failure to provide for their wives and children, hundreds committed suicide. And many turned on the families who toiled alongside them. One soldier settler, again from Northern Victoria, battered his wife and four-year-old daughter to death, then slit his own throat. It wasn’t just the shellshock that led Frank Wilkinson to do this. A man awarded the Military Medal for bravery at Messines survived the war but not the peace. He couldn’t bear another day working an unworkable holding.

Soldier settlement was one of the great failures of Australia’s repatriation policies. ‘Delicate men’ were placed on ‘heavily timbered blocks’, blind men charged with the care of a thousand sheep, nerve cases given flocks of equally nervous poultry to care for. From the earliest days of the scheme government inspectors across the country record men with mechanical claws clutching at fruit, they watched legless men contrive to grub out trees and badly gassed cases—men barely able to speak—trudging stoically across their properties. The plight of the psychological casualties of war—men like Frank Wilkinson above—defies credulity.

But it would be a serious mistake to read repatriation files as an unmitigated tragedy, an endless catalogue of horrors. Many of the repatriation cases cited above were classified TPI, but, as historians have acknowledged, ‘disability’ itself is a problematic category. A veteran’s post-war health often deteriorated but sometimes improved. Repatriation files enable us to chart the cycle of an illness or injury, and place disability, as Marina Larsson has put it, ‘in a social and familiar context’. Some soldier settlers did succeed, though, more often than not, that success relied on the failure of others. Men bought up abandoned blocks and consolidated their holdings. Finally, whilst pain and suffering emanate from these records, there’s also evidence of great courage and immense resilience. Again Bertram Byrnes’ case is instructive. Consider how he dressed the day they took that photograph. Byrnes wore his Sunday best, a bow tie neatly knotted beneath that twisted face. He looked directly into the camera, head held high, his gaze unyielding.

Byrnes was a man marred by war, his face ‘terribly disfigured’, but there is little in the file to suggest he defined himself as a victim. Byrnes was mindful of his entitlements and all too prepared to fight for them; he appealed (successfully) against reductions to his pensions and—when free medical attention was withheld—took his case directly to Deputy Commissioner:

...isn’t it a fact sir that some 14 years ago we T.P.I. pensioners were granted free medical treatment for other than war caused injuries any how that’s about how long I have been receiving it for all my illnesses both here and in Concord Hospitals I assume I am right in believing I am entitled to free medical treatment for other than G.S.Wounds.

Whilst Byrnes tone is polite it is also firm and insistent. The Deputy Commissioner was told to treat his case as ‘urgent’. Byrnes never expressed shame at this injury. To the contrary. He saw himself as a returned man who had ‘done his bit’—a strong sense of moral economy informed his tireless petitioning. His status was that of a veteran rather than a victim. He would march and wear his medals on Anzac Day. Every Anzac Day we commemorate the sacrifice of men and women sent to war. Acknowledging the struggles of those who returned seems no less important.

To date, the NAA has been able to digitise less than 10% of one of our country’s richest archival holdings. Completing that project, and telling the other half of a nation’s war story, might begin to honour the promise made that generation.

Author:

Professor Bruce Scates teaches history at the Australian National University. He is the author of A Place to Remember: A History of the Shrine of Remembrance, Return to Gallipoli, On Dangerous Ground and several other studies of war and memory. He chaired the Military and Cultural History Panel advising the Anzac Centenary Advisory Board and initiated the digitisation of repatriation records at the National Archives of Australia. He also led a research team examining the history of soldier settlement and is the lead author of Anzac Journeys, The Last Battle and World War One: A History in 100 Stories.

Updated