- Conflicts:

- Somalia (1992-94), Rwanda (1994), Bougainville, Papua New Guinea (1997-2003), East Timor (1999-2005, 2009), Solomon Islands (2000-2003), Sierra Leone (2000-2003), Afghanistan (2001-21), Iraq (2003-2009), Syria (2014-)

- Services:

- Army, Air Force, Navy, Peacekeeping operations

by Anna Taylor

photographer Vlad Bunyevich

In 2003, soon after I arrived in Melbourne to work at the Shrine, I visited the Immigration Museum and met with students of English as a second language. Some were displaced people who had lived for many years in refugee camps before coming to Australia. I wondered what circumstances could have led them to leave their homes and communities; leave family perhaps forever, to spend years in camps, with the hope of being relocated to a country they knew nothing about.

I imagined an exhibition to address these questions but it would be 17 years before this was realised. In the intervening years, Shrine special exhibitions considered European immigration due to the Second World War, the cultural expression of immigrants within internment camps, and when they settled here after the war. We gained further insights, working with Vietnamese Australians, as to why they risked everything to come here.

From 2017–18, we have increasingly interacted with veterans of recent conflicts and peacekeeping. This brings insights into relatively recent experiences; still quite raw for some veterans. Innovations such as head cameras, can transport us to the frontline as never before. Veterans share their stories; informally, when donating memorabilia; working with curators on an exhibition; or, formally, when addressing an audience. Some say that storytelling helps to validate their war experiences and assists in their transition to civilian life.

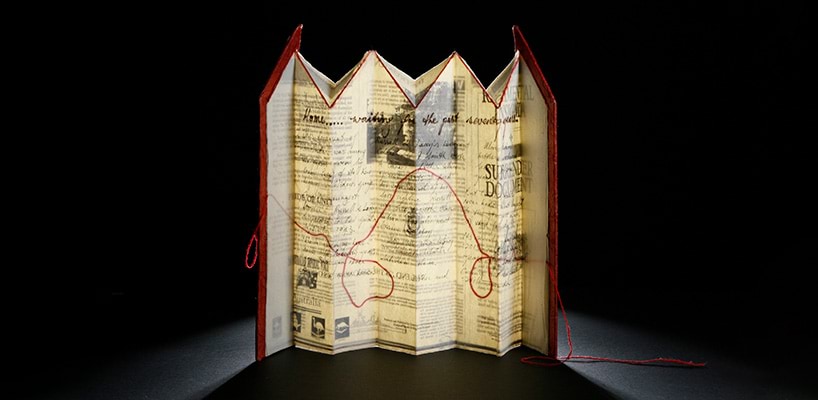

Inspired by their observations and the immediacy of their stories, I conceived an exhibition with a contemporary focus that would combine veterans’ perspectives with those of recent arrivals to Australia, as foreshadowed all those years ago. The result is Changed Forever: Legacies of Conflict, in which personal stories reveal the physical and emotional dislocation of veterans and migrants by conflict, and the diverse ways in which they have reconciled these experiences with their transformed lives.

We had had limited contact with migrant communities, and none with recent migrants who had come here because of war. We connected with organisations including the Centre for Multicultural Youth and Foundation House, who provided excellent training in cultural competencies and trauma management. Our first informal encounter with a South Sudanese teacher in Dandenong left us painfully aware of how unprepared we were for the realities of these stories. Thereafter, we not only prepared more fully but generally worked with the support of an intermediary to connect with storytellers.

We partnered with Jesuit Social Services and the Australian National Veterans Arts Museum who have given invaluable introductions to storytellers and assisted by attending interviews, bringing their extensive experience and knowledge of individuals to the process.

In 2018, the Shrine commenced an oral history program asking subjects to talk about their experiences of conflict and resettlement: in the case of migrants for the first time and for veterans, on their return from overseas service.

They welcomed opportunities to speak with us about their experiences, inspired us with their willingness to share, and were articulate and candid. Many shared the hope, that, by revealing their histories, they might help build understanding and relieve the sense of isolation felt by some. Deena Yousif from Iraq comments:

Your place of birth determines how safe you are and safety in this world is the most important thing. It takes strength to leave loved ones, to lead a life that is safe.

The interviews confronted questions of how people lived through war, how they reacted when faced with life or death situations. Few recorded having time to discuss their options: most ran for their lives, hungry, thirsty and in great danger, before crossing a border to relative safety, but fresh uncertainty. Often faced with living on someone else’s land with no legal status—reliant upon international aid for the necessities of life—they describe the inevitable rebellion of locals, displaced by refugees from their land, and seeing refugees receiving food and water, while they struggle to feed themselves.

Reproduced courtesy of Isaiah Lahai

Migrant stories bear witness to the heartbreaking necessity for families to separate—in some cases never to be reunited. Already displaced from Afghanistan, Reza Shams, with his mother and brother, decided who of them would leave their interim home in Pakistan, in hope of finding a better life. Reza made the perilous journey to Australia, where he is making a new life. Parents will risk everything to ensure education and safety for their children. Jumabi Mohamad Ali and her husband Ali Sharif, risked their lives to travel to Australia to ensure for their children the education denied them by their Rohingya ethnicity.

Reproduced courtesy of Jumabi Mohamad Ali

Defence personnel have historically intersected with civilians on the frontline. They have served, and some died, in the countries represented by migrant stories in Changed forever. Their eyes have been opened to the hardship and perseverance of people, working for the necessities of life, in isolation from the world as we know it, or denied these necessities by historical or political inequities.

Helen Ward, a member of the Royal Australian Navy, served in central Baghdad in 2007, embedded with United States Headquarters. She tells a story that illustrates what she learnt about sacrifice there. She recalls: the Americans shipped in 50 wheelchairs, made of plastic chairs with bicycle wheels attached, so they could operate in the desert. As they distributed them, a gentleman walked towards them, carrying his adult son. When they moved to help him, the man said:

I’ve carried my son for thirty years

I can carry him the last 300 metres to get the chair.

David Robertson, Australian Army, saw in Afghanistan:

… how harsh life can be, not only in conflict, but living in a small village where you grow your own food and work so hard for the necessities of life.

Although those villagers didn’t have much, they had community.

Veterans celebrate the bonds formed in service, and grieve for the loss of close friends, not only in war, but because of it. In the days following Anzac Day 2019 there were seven veteran suicides. Attitudes towards Australia’s largest commemorative service are complex. While many are proud to march, some spoke of feeling disconnected from Anzac Day. They respect the Anzacs of the First and Second World Wars, but don’t all identify with them; some unable to conceive that they are equally worthy of reverence. While turning away from conventional rituals, young veterans today often choose social media which can provide anonymity, if required. Simultaneously, social media connects fellow service men and women, some over great distances, who share experiences in common, offer unqualified support and require no explanation.

photographer Michael Christofas

Service women, and some younger men, reported being challenged when wearing their medals, because spectators did not identify them as veterans. The face of Australian service people is changing, reflecting our evolving society. No longer exclusively white and male, never representing only one religion, the face of Anzacs is also redefined by the enlistment of women in increasingly diverse roles and waves of post-conflict migration to Australia.

Changed Forever looks at some of the war experiences that have contributed to our community today, as experienced by our service men and women, and by those who have fled their home and communities and travelled to find safety far from all that is familiar.

Reproduced courtesy of Kellie Dadds

Stories explore reconciliation between the men and women of the Australian Defence Force and the civilian community, and between veterans and their estranged families and friends. For migrants: reconciliation between a past they can never retrieve and new lives, with the challenges and rewards that this offers. They reflect on what they miss most; on feelings of disconnection, both from a world once familiar and one they are encountering for the first time.

The personal stories in Changed forever aim to expand our understanding of what civilians and service people go through in war; to bridge the gap in comprehension, between Australians at home and service people who have served abroad and new arrivals. In short: to offer a more comprehensive view of Australians and war.

Barham Ferguson, a veteran of multiple deployments with the Australian Army, acknowledges the changes that overseas service has brought to his life.

…it would be simpler not to know certain things, but I would not change it.

He embraced:

… privileged access to the world, and perspective—everything changes once you get out of your comfort zone and go to these places. You learn about yourself and your country, for better and for worse. You gain wisdom.

Author:

Jean McAuslan recently retired as the Shrine’s Director Access and Learning. She joined the Shrine in 2003, providing special and touring exhibitions and leading concept and content development for the Shrine Galleries which opened in 2014. Jean led the exhibitions programs, managed the Shrine collection, schools’ programs and public programs, and 120 volunteers who support the Shrine’s activities.

Updated