- Conflict:

- First World War (1914-18)

- Service:

- Air Force

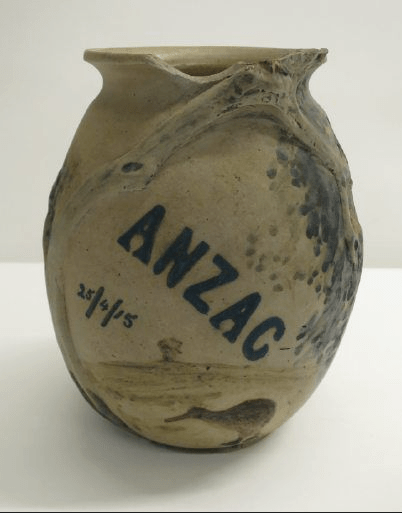

The name William Merric Boyd (1888–1959) is synonymous with Australian pottery of the 20th Century. Until recently there were few documented examples of Merric’s work that reflected his wartime experience. A recent donation to the Shrine of Remembrance unearthed a rare early piece from Merric’s career. The hand thrown vase features a relief gum tree that curves around the vase protruding at the neck. A relief kiwi grazes at the base of a serene landscape hand-painted by Merric's new wife Doris. The words ‘ANZAC 25/4/15’ are emblazoned across the vase. Damage sustained before it was given to the Shrine has resulted in the loss of the more sculptural elements. There are many questions as to why Merric would create a commemorative piece so distinct from other works during this formative time in his career.

In 1913 his family purchased an old orchard in Murrumbeena, southeast of Melbourne, where he constructed a house and studio. By 1915 he had an elaborate workshop, with equipment he had largely built himself, and was beginning to push the limits of his medium and challenge established conventions of pottery. He was also married to Doris Gough, who had studied with his brother Penleigh at the National Gallery School. Doris would contribute her painterly skills to the landscape decorations of Merric’s pottery in these first years of marriage.

Merric has routinely been described as an ‘eccentric’ and a pacifist. He adopted his wife’s religion of Christian Scientist and together they became preoccupied with the beauty of nature and its creatures—a theme that dominated his work throughout his career.

In 1915 all three Boyd brothers, Merric, Penleigh and Martin, were of military age. Merric, as a pacifist who held a strong sense of chivalry and community, must have felt conflicted. The youngest Boyd brother, Martin, spurred by seeing his classmates names appear on casualty lists for Gallipoli, was the first to enlist. Penleigh joined in November 1916 describing those who stayed behind as ‘coldfoots and shirkers’. In an obvious insult to Merric and Doris, he stated conscientious objectors were ‘mostly vegetarians and Christian Scientists.’ By 1916 Merric had been the recipient of two white feathers—implying cowardice—and Doris had given birth to their daughter, Lucy. Many of Merric’s cousins had already enlisted, with at least one serving at Gallipoli and another dying at Passchendaele. Merric’s Uncle Arthur A’Beckett, aged 47, served at Gallipoli as a Captain with the 4th Light Horse.

Following a failed attempt in 1916, Merric successfully enlisted in June 1917 as an Air Mechanic in the Australian Flying Corps. After four months of training he embarked for England and spent the war undertaking routine tasks, never seeing active service. At the close of the war Merric took advantage of the repatriation scheme by studying technical aspects of pottery at Stoke Technical School and received an invitation from Josiah Wedgewood to the potteries at Stoke-on-Trent. His course report states: ‘Particularly good work done, which should be very valuable to him on his return to the profession in Australia’. In October 1919 he returned aboard HMAT Euripides, where he held pottery classes as part of the rehabilitation program for ex-servicemen run by Army Education Services. Merric would continue to teach and share his knowledge with generosity throughout his career.

Although Merric’s war service was brief the war undoubtedly left a deep impression on him. We may never know the motivation behind the creation of this Anzac vase, but we do know it was created at a time when Merric would have felt unprecedented challenges to his religious and moral beliefs and a strong desire to contribute to the war effort.

He felt strongly that pottery ought not to be private, expensive or special in the exclusive sense... If you had a particular talent or bent, and you were able to organise it into creative effort that could serve others, then you should do that.

Arthur Boyd on his father, 1989.

Author:

Jenna Blyth was Collections Manager at the Shrine of Remembrance, and former Assistant Curator. Jenna has over 14 years’ experience in sharing stories and caring for cultural materials at museums and galleries.

Updated