- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

- Service:

- Army

John Vickery’s journey from Bunyip to the front lines of the Pacific theatre was anything but straightforward. This article examines Vickery’s multiple contributions to the Allied war effort as a war artist and commercial illustrator based in New York City during the Second World War.

John Vickery left Australia in the mid-1930s unaware that the dim prospect of a war in Europe would alter the course of his life and career. Like many young artists, he went in search of opportunity and adventure. By 1937, he settled in England where he and his wife found a welcoming circle of artistic acquaintances and, in the wake of the Great Depression, promising signs of a steady flow of commercial illustration work.

The looming war, however, disrupted the Vickerys’ plans to settle permanently and they decided to return to Australia. The journey home was via the United States (US) where Vickery had been offered some contract work illustrating magazine advertisements. He quickly became a sought-after illustrator managing assignments for a number of Madison Avenue advertising agencies. The Vickerys’ plan to return to Australia was put on hold indefinitely.

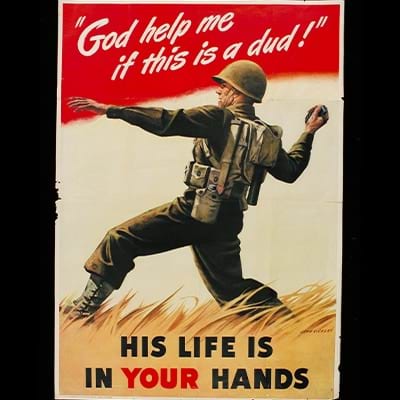

As the war effort spread to the US, Vickery’s talents were put to use producing posters and advertisements designed to mobilise the civilian population. Posters advertising the sale of war bonds, recruitment ads for ‘citizen soldier’ organisations and billboards encouraging a productive workplace soon became part of his stock-in-trade alongside the more conventional ads for automobiles, travel and other modern conveniences.

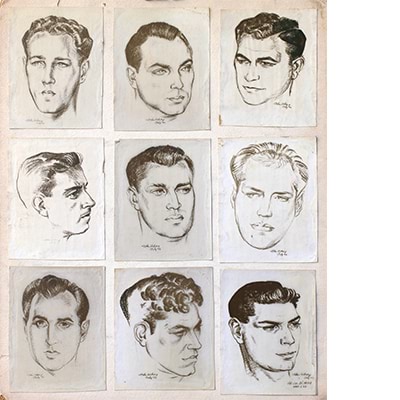

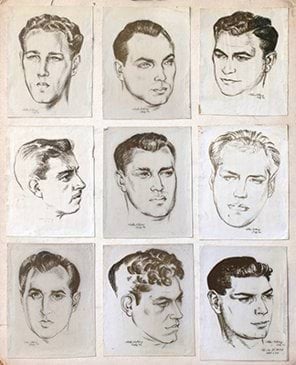

While important, Vickery viewed much of this work to be a waste of his talents. He tried to enlist, without success, and was keen to find his place in the war effort through other means. The opportunity came in 1943 when Vickery was invited by the army to participate in a sketching program at Walter Reed General Hospital. The program, which harked back to sideshow entertainment from the Vaudeville era, was the idea of a young New York artist, Henrietta Bruce Sharon. Sharon approached the Army and Navy with a proposal to sketch patients in military hospitals. The patients could then keep the drawings or send them home.

The benefits of the program for patient wellbeing were immediately apparent. The process of being sketched provided stricken soldiers with welcome distraction, conversation and entertainment. Each visit by a sketch artist resulted in a general improvement in patient mood.

The program quickly expanded to cover all military hospitals in America. In 1944, it was incorporated into the overseas hospital circuit of the United Services Organisation (USO) camp show entertainment tour. Vickery was the first artist selected for an overseas posting having already sketched hundreds of wounded soldiers across the US.

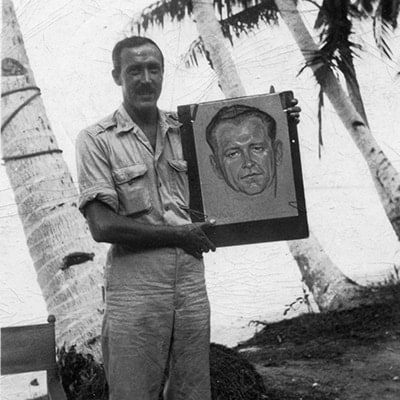

Vickery arrived in the South West Pacific theatre in October 1944. He was given the honorary rank of Captain in case of capture and spent the next eight months with the US Army touring Field Hospitals, Evacuation Hospitals and Battalion Aid Stations in New Guinea, the Netherlands East Indies and the Philippines. Vickery produced over 650 portraits of soldiers suffering physical and mental injury. For these soldiers, unable to attend the larger USO performances, the time spent being sketched was the only entertainment on offer.

The USO provided instructions outlining how artists should interact with patients. One instruction read:

Do not mention anything about their wounds, sickness or condition, nor notice that they have lost a limb. Talk to them as you would to a friend or healthy stranger. If they mention their sickness, listen attentively, and gradually try and get into another subject.

At the conclusion of each session the finished sketch was given to the sitter and a photostat of the sketch was sent to the patient’s nominated recipient.

At a press conference in 1945, Vickery noted that the chief concern of all the soldiers he met was to look as normal as possible so as not to worry their families. For this reason, face wounds were omitted, GI haircuts touched up, beards and ‘fantastic’ moustaches removed. Vickery first attended to the soldiers most critically wounded. In some cases, his sketches would be the last image families would see of their loved one.

While her husband toured the hospital circuit, Claire Vickery donated her time and efforts to the Allied war effort as secretary of the Anzac and Southern Cross clubs of New York. These associations aimed to provide Allied soldiers from Australia and New Zealand with accommodation and entertainment during their stop-overs. The club’s motto was:

We do the impossible right away. The miraculous takes a little longer.

News reports from the time estimated that Claire provided assistance to over a thousand Allied servicemen passing through New York. She received The King’s Medal for Service in the Cause of Freedom and a personal letter of gratitude from Australian Prime Minister Ben Chifley. Never one to forget his Australian roots, in 1941 Vickery designed an Anzac themed Christmas card which was sold to raise funds for the ANZAC War Relief Fund in New York.

On his return to the US, Vickery took on a post-war role as Chairman of ‘group counselling’ for The Society Of Illustrators Veterans’ Program. The initiative assisted returned soldiers with finding work in the field of commercial art and illustration and was described as ‘a much more practical expression than parades and torn-up telephone directories.’ The art jobs for veterans programs provided professional guidance and assistance in the preparation and presentation of a job winning portfolio, intensive refresher courses, access to continuing undergraduate study and group counselling with a panel of practicing commercial artists alongside an Art Director from an advertising agency.

Monthly group counselling panels attracted on average of 75 veterans per session. One such veteran, Sam Savitt, had served with the US Army Corps of Engineers on the Ledo-Burma Road project. Savitt attended painting classes with Vickery and Vickery arranged for Savitt to rent a studio on the floor below his own in Lexington Avenue. With Vickery’s assistance, Savitt went on to have a successful career as the artist behind The Lone Ranger and Trigger comics. Savitt’s gratitude was so great he named his daughter Darah Vickery. It was an unusual honour for a war artist, but strangely fitting for someone who used his skills as an artist and illustrator to provide comfort and assistance to soldiers rather than merely documenting their trials.

Author:

Toby Miller is Exhibitions and Collections Research Officer at the Shrine of Remembrance.

Updated