- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

- Service:

- Army

Following the successful battles of Bardia, Tobruk and Derna in January and February 1941, the 6th Australian Division found themselves providing garrisons for the towns they had captured from the Italians. As Operation Compass under General O’Connor continued to push Benito Mussolini’s forces back to the Tunisian border, in Berlin momentous decisions would soon change the course of the war. From these decisions, the Greece, Crete and Syrian Campaigns would soon embroil the 6th and 7th Australian Divisions.

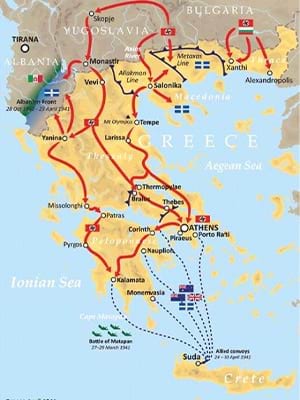

Increasingly worried about the Italian reversals in North Africa and Greece, German leader Adolf Hitler ordered his military commanders to bring forward their planned Greek invasion. By late February, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had dispatched his Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden to reassure the Greeks that British Empire forces would come to their aid if necessary. Events developed rapidly and by early March the decision had been made; 6th Division and the New Zealand Division would be deployed to Greece immediately. General Thomas Blamey was put in command of this reborn ANZAC Corps. The North African campaign ground to a halt, despite the arrival of elements of the 7th and 9th Australian Divisions. For two young indigenous Australian men from South-Western Victoria, these decisions would change their lives forever.

Reg and Harry Saunders, from Lake Condah near Portland in the Western Districts, had enlisted in the 2ndAustralian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) soon after war was declared. Twenty year old Reg joined the 2/7th Battalion, 6th Division in April 1940 and after basic training soon found himself on a troopship bound for the Middle East. 18 year old Harry was initially knocked back when he tried to volunteer but, after travelling to Melbourne, was successful. He would also serve with a Victorian unit, the 2/14th Battalion, 7th Division, which departed Australia soon after his brother. They would meet again in December 1940, on leave in the ancient city of Jerusalem. Working as timber cutters in the forests outside of Portland must have seemed like a world, and a lifetime, away. It would be the last time they would see each other.

On 13 April, a week after the German invasion of Greece, Reg Saunders and the rest of 2/7th Bn arrived at the port of Piraeus, Athens and were put on trains to the north to join the rest of 6thDivision. After months in the baking desert, the green farmland and mountain ranges were a welcome change, although the bitterly cold weather was a shock. Taking up defensive positions astride the Brallos Pass, the Victorians dug in as quickly as they could once it became clear that the units further north than them were not able to hold the advancing German divisions. Due to the mountainous terrain support weapons, ammunition and supplies were carried by the infantry or on the backs of donkeys. German air raids were almost constant as few Allied aircraft were available to provide air support. By 19 April their positions were untenable and Reg and the rest of his unit were forced to withdraw. Bren guns provided the only air defence and were little help against waves of Stuka dive-bombers and Messerschmitt fighters. Every hour the German aircraft would come hurtling in, cannons blazing. Weary diggers would leap over the tailgates of lorries and sprawl into roadside culverts, firing up at the hated enemy. After the planes had departed the convoy would form up again, minus those trucks blazing on the side of the road, and continue the move south towards Athens along narrow, winding roads.

Under the hot desert sun of Egypt, Harry Saunders and his comrades in 2/14th continued their training and were then deployed to defensive positions at Mersa Matruh on the Libyan border, ready to hold back the Axis advance. Many members of 7th Division hoped that they would see action.

By this time, Reg and his mates felt they had seen enough for a lifetime. On the evening of 25 April, Anzac Day, they took shelter in an olive grove in the hills above the Greek port of Kalamata, south-west of Athens. The Royal Navy was due to evacuate them the following day. Another day passed and still they waited, but at least they had a chance to catch up on desperately needed sleep, have a cup of tea and clean their weapons. On 27 April their prayers were answered. The Dutch liner Costa Rica was in harbour, escorted by Royal Navy destroyers. Soon they departed, under air attack the whole way. In sight of Crete their luck ran out as a German bomb wrecked the engine room of the Costa Rica. As the liner began to take on water, an orderly evacuation took place; the 2/7th didn’t lose a man. Thankful to be ashore they had a few days to relax, although unbeknownst to them Hitler had met with his paratroop commander General Kurt Student on 21 April. The only topic of discussion was Operation Merkur – the airborne invasion of Crete. The island was living on borrowed time.

By mid-May German air raids were almost incessant as they sought to destroy the anti-aircraft defences of the three airfields of Maleme, Heraklion and Rethymnon. These were the key to Crete. If the Germans captured them, they could land as many men as they needed to overrun the island. And while the commander of the force on Crete, New Zealand General Bernard Freyberg, had enough men, they were very poorly armed and had virtually no air support.

It looked like it would be a repeat of the Greek debacle. At 6:45am on 20 May, another German air raid began, but looking north towards Greece hundreds of slow moving transport planes could be seen following the bombers and fighters. The invasion of Crete had begun.

As thousands of paratroopers floated down along the north coast of Crete and gliders carrying many more elite German soldiers slid to a halt in dusty fields, a veritable wall of automatic weapons fire poured from Australian and New Zealand positions. Hundreds of Germans died before their feet hit the ground and many others were killed as they struggled to untangle themselves from their parachute lines and shrouds. The fighting was brutal and merciless, with no quarter asked, nor given. Cretan civilians joined in the fighting, slaughtering any Germans they could get their hands on. German casualties mounted, but as more and more of their troops landed on the island, they gradually forced the ragtag Allied defenders back. Just before midnight on 22 May it was clear that the paratroopers had control of Maleme airfield. The island was lost, it was just a question of when.

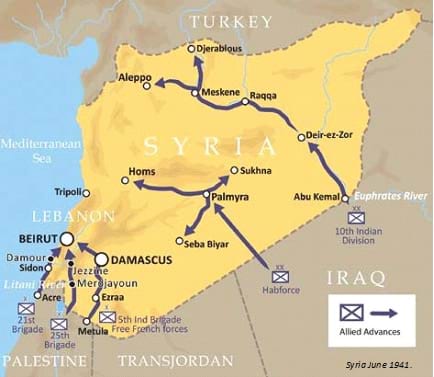

On the same day back on the Libyan border the Commanding Officer of the 2/14th briefed his officers. They were to hand over their positions to an incoming South African unit and board transports for Palestine. Harry and his mates collected all of their possessions and boarded trucks, moving slowly towards the Syrian border. Rumours began to fly that finally, they were to see action. For once the rumours were correct. The British government was worried that the Germans would use the Vichy French territories of Syria and Lebanon as a base to launch aerial operations against Palestine and Egypt and threaten the Suez Canal. The Allied attack was to occur on 8 June, spearheaded by the 7th Australian Division. Harry and his mates would soon have all the action they could wish for, but against the French Foreign Legion not the Germans or Italians.

Once the decision was made to evacuate Crete, the survivors began to disengage and retreat southwards through the White Mountains and then onto the only safe evacuation beach on the coast, Sfakia. The two Victorian battalions, Reg’s 2/7th and the 2/8th, provided the rearguard setting up roadblocks and allowing stragglers to join the retreating columns. The Luftwaffe strafed and bombed them incessantly. Finally, on the morning of 27 May a chance to stand and fight occurred, as the Australians and their New Zealand comrades waited in positions along 42nd Street, outside the town of Canea. Advance elements of the German 5th Alpine Division were seen raiding an abandoned supply store and when some of them approached to within 25 metres of the ANZAC positions, Reg and his mates opened fire. Kiwis and Aussies burst from the olive groves with bayonets fixed and with a pent up roar charged the Germans, driving them back in disarray, killing hundreds of them. While it could not turn the tide of the campaign it did buy the retreating forces a precious day of respite.

In good order, although greatly depleted in numbers, the 2/8th and 2/7th continued to provide the rearguard, eventually arriving at the evacuation beach on 1 June. Thousands of men had been taken off by the navy each night, but more remained. In darkness before dawn the 2/7th lined up and were addressed by their CO, Colonel Walker. No more boats would be coming, the evacuation was over. Although shocked, the 2/7th did not break ranks nor complain. Walker told them they had two choices, split up and take to the hills and try to make their own way home or surrender to the victorious Germans. Reg wasn’t going to surrender, so he set off into the mountains. Less than two months earlier, when the 2/7thhad sailed for Greece it had nearly 800 men. After the fighting on Crete, 16 men would make it back to Egypt. For 6th Division, Greece and Crete had been a disaster. They had lost over 6,000 men killed, wounded and captured. The division would have to be rebuilt before it could see action again.

Back in Palestine, Harry and the 2/14thwere making final preparations for the invasion of Syria. In the pre-dawn darkness on the morning of 8 June the assault was launched with 2/14th in the lead, attacking the Vichy French forward defences. 21st Brigade continued the advance along the coast towards the Litani River and soon the 2/14th was heavily engaged in the coastal area between the Litani and Zahrani Rivers, taking a number of casualties. Overhead P-40 Tomahawks of the RAAF provided air cover.

Back in Palestine, Harry and the 2/14thwere making final preparations for the invasion of Syria. In the pre-dawn darkness on the morning of 8 June the assault was launched with 2/14th in the lead, attacking the Vichy French forward defences. 21st Brigade continued the advance along the coast towards the Litani River and soon the 2/14th was heavily engaged in the coastal area between the Litani and Zahrani Rivers, taking a number of casualties. Overhead P-40 Tomahawks of the RAAF provided air cover.

Within days the 2/14th was moved inland to support the 2/31st, which was held up outside Jezzine. The fighting was even more ferocious here with many more casualties suffered by the Australians. Harry and his best mate Alan Avery were two of them, wounded by a grenade that exploded nearby. The fighting continued for several weeks as the Vichy French resisted far more fiercely than the British had expected. More than 400 Australians were killed in action and over 1,000 wounded. Eventually on 12 July, an armistice was signed and four days later the victorious Australians entered Beirut. The Syrian Campaign was at an end. While neither of these campaigns changed the course of the war they ensured that when the Pacific War broke out battle-hardened Australian soldiers were ready to meet them and, eventually, defeat them.

After eleven months hiding out on Crete, Reg was finally evacuated by a Royal Navy trawler on 7 May 1942. Having evaded the German occupation force with the assistance of brave Cretan civilians who risked their lives to shelter Allied troops, he and the other soldiers were overjoyed to finally escape. Reg would return to Australia before rejoining the 2/7th and serving in the Wau-Salamaua Campaign in the mountains of New Guinea. In 1944 he would be recommended for officer training by his CO and become the first indigenous Australian Army officer. After the Second World War he found it difficult to return to civilian life and once again experience the racism that had been non-existent in the Australian Army. When the Korean War broke out in 1950 he joined up again and served as a company commander in the 3rdBattalion, Royal Australian Regiment. His final job would be working for the Office of Aboriginal Affairs in the late 1960s and 70s before passing away in 1990.

Harry’s story is much shorter. After the Syrian Campaign and garrison duties, the Japanese attacks in the Pacific saw 7th Division return to Australia and shortly thereafter deployed to Papua New Guinea. Along with the Victorian militia unit, the 39th Battalion, the 2/14th would be the first unit to meet the Japanese advance over the Kokoda Track. After that campaign 21st Brigade were withdrawn to Port Moresby to rest and recuperate before being sent back into action. On 29 November 1942, in the desperate fighting to take the northern beachhead town of Gona, Harry was killed in action. He was 20 years old.

Author:

Dr Adrian Threlfall is a regular contributor to Remembrance. Adrian has seen service in the Australian Army Reserve and lectured in military history at Victoria University. He is an educator at the Shrine of Remembrance, where he provides learning experiences to students on Australian service in times of war and on peacekeeping operations. Adrian’s first book entitled Jungle Warriors: From Tobruk to Kokoda and Beyond is for sale in the Shrine bookshop. His second, Reg Saunders: An Indigenous War Hero, is also available.

Updated