- Conflicts:

- First World War (1914-18), Vietnam War (1962-73)

- Service:

- Army

by Dr Ian Jackson

It has been said that ‘History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme’. In 1916–17, at the height of the First World War (1914–18), two referendum campaigns showed that Australia was bitterly divided over the issue of conscription. Fifty years later, with Australians fighting in the Vietnam War (1962–75), the government’s decision to commit National Servicemen to the conflict again caused passionate debate. In both cases the prospect of sending men overseas to fight against their will caused a deep and emotional dispute that split the government, communities and families. The parallels between the two periods were clear to many on both sides of the debate in the 1960s.

Neither in 1916, nor in the 1960s, was compulsory military service itself a new thing in Australia. Australia first adopted a system of compulsory military training for home defence in 1911, which ran until the 1930s. And in the 1950s—under the first National Service Scheme—227,000 18-year-olds had been called up for six months service in the Army, Navy, or Air Force, again largely serving within Australia.

While both these forms of mandatory service had caused some debate, training men in Australia was much less controversial than requiring them to fight overseas. Service in Australia was seen by many as an insurance, giving men the skills needed to defend the Australian homeland against invasion. Compulsory service overseas required more contentious justifications: that Australia’s security depended on its commitment to its allies, or that Australia was morally required to intervene against foreign tyranny.

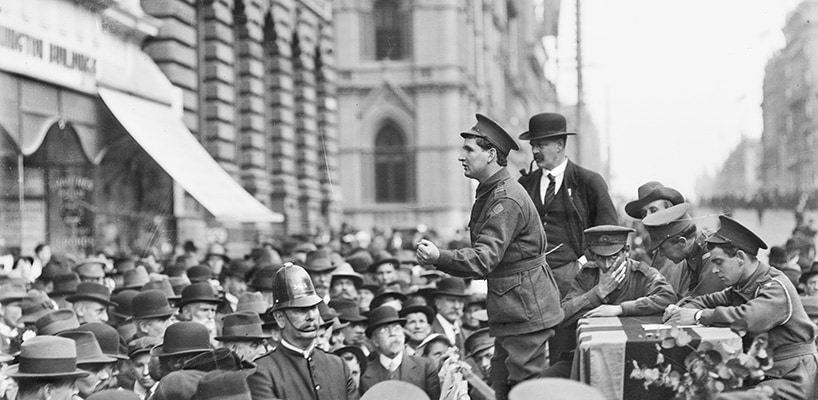

In early 1916, faced with declining enlistments and a more drawn-out war than expected, the British government introduced conscription. Billy Hughes, Australia’s Prime Minister, returned from a visit to England at the end of July convinced of the need for Australia, which he called an ‘island of volunteerism in a great sea of conscription’, to do the same.

Referendums were a familiar event in Australian politics, built into the constitution as a way for the people to have the final say on changes to Australia’s system of government. What made the First World War conscription referendums different to those before or since, was that there was no legal requirement to hold them as they did not seek to change the constitution. For this reason they are sometimes referred to as plebiscites, although only the word ‘referendum’ was used at the time.

Instead, as with recent referendums proposed by David Cameron in the United Kingdom and Malcolm Turnbull in Australia, the 1916 referendum originated as a response to deep divisions within the governing political party. In 1916 the Senate, dominated by Labor senators who opposed conscription, was unwilling to amend Australia’s existing compulsory service law to allow conscripts to be sent overseas. Hughes hoped that calling a referendum would create a mandate for conscription from the people themselves that the Senate could not ignore.

Hughes believed that the survival of freedom itself depended on the survival of the British Empire and Australia had to play her part. At rallies for the Yes campaign, he argued that relative to her population, Australia had only half as many men enlisted as Britain did. He asked the women of Australia:

What is your answer to the boys at the front? Are you going to leave them to die? What is your answer to Britain, to whom we owe so much; to France, to Belgium?

Hughes asked all Australians ‘to prove in this referendum whether they want to be their own masters, or slaves’.

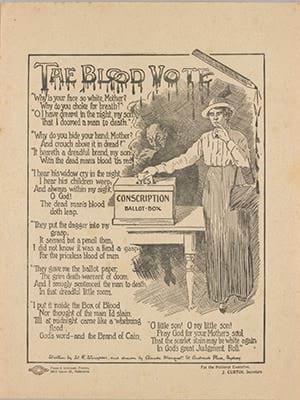

Much of the union movement opposed Hughes, appointing an activist named John Curtin as secretary of the Anti-Conscription League (ACL). The ACL’s most famous leaflet described a vote for Yes as ‘The Blood Vote’, featuring a mother who ‘dreamt in the night, my son/That I doomed a man to death’.

Hughes had underestimated the strength of opposition to conscription. On 28 October 1916, 1,087,557 Australians voted ‘yes’, and 1,160,033 voted ‘no’.

In the aftermath of the failure of the first referendum, Labor split. Billy Hughes and his supporters formed a new party, the Nationalist Party, in conjunction with Liberal supporters of conscription. Hughes called and won an election, but on a promise not to introduce conscription without a further vote. This second referendum was held in December 1917. This time the government proposed a ballot to randomly select only as many men as were needed to make up the shortfall in voluntary enlistment.

The most prominent No campaigner in 1917 was Daniel Mannix, Archbishop of Melbourne. The Irish-born Mannix had been appalled by the British repression of the 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland, but played a relatively small role in the first referendum. Hughes’ statements blaming Mannix for the defeat, and implying that those who opposed conscription were treasonous ‘Sinn Feiners’, goaded Mannix into action in 1917. His vehement campaigning speeches against conscription drew large audiences. He argued that Hughes wanted ‘to put the people of Australia under the heel of military domination’ while fighting no more than a ‘sordid trade war’, proudly proclaiming: ‘I make no apology for putting Australia first and the Empire second.’

This time 1,015,159 voted ‘yes’ and 1,181,747 voted ‘no’.

The divisions in Australian politics and society caused by the conscription debate ran deep. The union movement celebrated the defeat of a government they had once supported. Meanwhile, Mannix’s opposition fuelled years of unfair stereotyping of Irish and Catholic Australians as disloyal.

The issue of conscription remained unresolved on the outbreak of the Second World War and recruitment of another volunteer Australian Imperial Force. By 1943 the former anti-conscription leader John Curtin had become Prime Minister. Now his stance reversed completely. Perceiving an existential threat to Australia from Japan, he argued for—and won—the right to send conscripts beyond Australia’s shores. For many in his party, conscription in the Second World War was justified only because Australia itself seemed threatened.

The 1950s National Service Scheme was introduced with bipartisan support. The Vietnam War, by contrast, was controversial from the start, and much of the controversy came to focus on the question of conscription. Once again Australians were fighting in a far-off country in alliance with a great and powerful nation—this time the United States of America, instead of Britain—against an ideological enemy, once Prussian militarism, now Communism.

At this time there was a revival of interest in the First World War referendum campaigns. L C Jauncey’s history of the campaigns from an anti-conscription perspective, The Story of Conscription in Australia (1935), was republished in 1968. In 1965, University of Melbourne historian Barry Smith wrote a pamphlet for secondary school history students about the First World War conscription referendums. Smith picked up on the fundamental question those referendums had raised:

Perhaps no government, or any majority which sustains it, has the moral right to compel a man to engage in killing. And by what dispensation does government compel men to serve a cause in which they do not believe, in a war they did not make?

In the context of 1965, these were not abstract questions. In 1964 the Menzies government, citing the threat of Communism in Asia and Confrontation with Indonesia, had announced the reintroduction of National Service (abolished in 1959), with men called up by a ballot based on their date of birth. The resonances of history would not have been lost on Smith or on his student readers, liable to find themselves or their brothers called up to fight in Vietnam in the near future. If the Australian people had rejected conscription in 1916 and 1917, should they do the same in 1965?

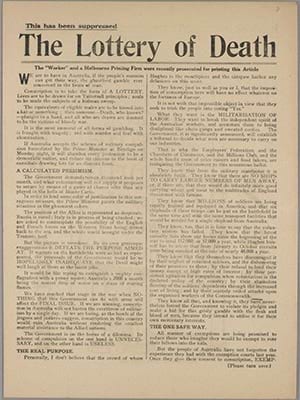

Arthur Calwell, Leader of the Opposition, had campaigned against conscription during the First World War. He described the National Service ballot system as a ‘lottery of death’—reviving a phrase first used in 1917 to describe the proposed First World War conscription ballot.

In response, Prime Minister Harold Holt retorted in Parliament that:

On the defence matters, [Calwell] cannot get his mind outside the conscription issues of 1916 and 1917. What Australia needs is a government which faces up to the reality that here we have a country which is expected to shoulder its own share of obligations.

In his address to voters before the 1966 election, Calwell rejected conscription on principle as ‘immoral’ and ‘unjust’, as well as opposing involvement in the ‘long, cruel dirty war’ in Vietnam. His emotive appeal to parents echoed the ‘blood vote’ rhetoric of 50 years before:

There are 600,000 Australian mothers with sons between 15 and 20 years of age... I call on those 600,000 mothers and their husbands and their other sons and daughters to tell Mr. Holt that the lives of their eligible sons are too precious to be squandered by the man who has pledged this country to go all the way with L.B.J.

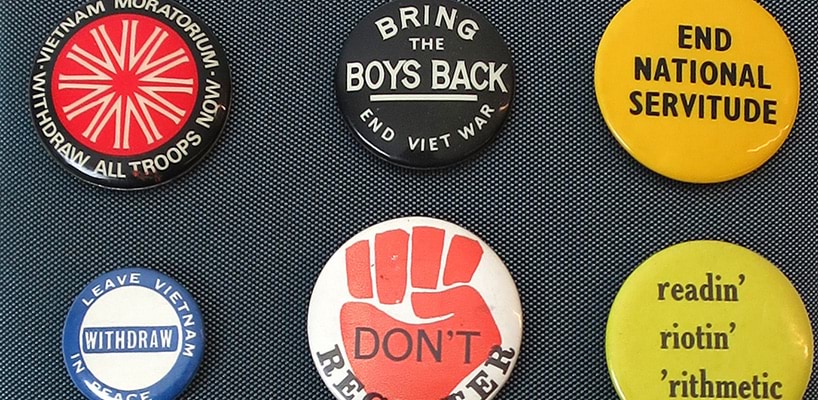

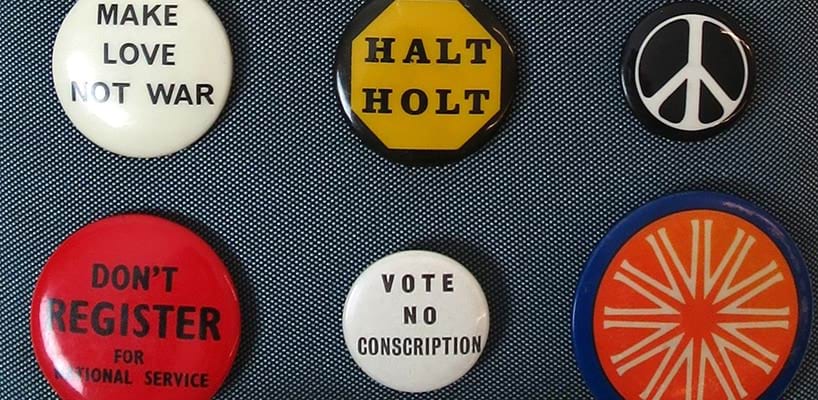

Holt won the election but the controversy continued. By the early 1970s the Moratorium marches drew large crowds to protest against the war and conscription. Anti-conscription campaigners encouraged young men to avoid registering for the ballot and to refuse to serve if called up. One leaflet’s list of tactics to avoid enlistment included ‘Be Militant’, ‘Be “Gay”’, ‘Go Bush’, or ‘Leave the Country’.

In December 1972, the incoming Whitlam Government suspended the National Service Scheme, although the legislation allowing conscription for overseas service was not repealed until 1992. In total, from 1965 to 1972, 63,700 men had been called up for two years National Service, of whom 15,300 served in Vietnam.

Whether conscription was justified, in 1916 or in 1966, remains a contentious issue to this day, with historians of left and right usually taking different sides. This is not surprising, for the same fundamental questions were raised in both periods. These include how the demands of the nation in a democracy can be reconciled with the freedom of the individual, what rights and duties citizenship entails, and how Australia’s security should best be ensured: by active support of allies overseas, or by concentrating on the defence of Australia itself.

Updated