- Conflicts:

- First World War (1914-18), Second World War (1939-45), Vietnam War (1962-73), New Zealand War (1860-66), Boer War (South Africa) (1899-1902), Boxer Rebellion, China (1900-01), Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) (1947-1951), UN Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (1948-1985), Malayan Emergency (1948-60), UN Commission on Korea (1950), Korean War (1950-53), UN Observer group in Lebanon (1958), The Congo (1960-1964), Yemen Observer Mission (1963-1964), Indonesian Confrontation (1963-66), Cyprus (1964-2017), India-Pakistan Observation Mission (1965-1966), Rhodesia (1979-1980), Sinai, Egypt (1982-86, 93-), Namibia (1989-90), Uganda (1982-1984), Iraq-Iran Military Observers (1988-1991), UN Mine Clearance Training Team, Peshawar, Pakistan (1989-1993), First Gulf War (1990-91), Cambodia (1991-93), Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia (1992), Somalia (1992-94), Rwanda (1994), Haiti (1994-95), Mozambique (1994-2002), Guatemala (1997), Bougainville, Papua New Guinea (1997-2003), East Timor (1999-2005, 2009), Solomon Islands (2000-2003), Sierra Leone (2000-2003), Ethiopia and Eritrea (2001-2013), Afghanistan (2001-21), Iraq (2003-2009), Sudan (2005-2011), South Sudan (2011-), Syria (2014-)

The First World War (1914–18) resulted in unprecedented losses for civilians and service people worldwide. Post-war grief gave rise to commemoration through remembrance ceremonies for veterans and their communities and a strong impetus to inform and thereby ensure that future generations would not forget what had been sacrificed for a better future. Today, veterans of recent conflicts express their desire to have their stories told; some saying that without this acknowledgement and recognition they feel disconnected from their own life or death experiences. Others speak of the value of a place like the Shrine of Remembrance in creating connections between those who are serving abroad and the people at home. They seek some focus on the present.

Relationships between the past, present and future will always be preoccupations in a memorial such as the Shrine. The additions to symbolism that have occurred with each major development at the Shrine, convey response to social change and reflect that memorials are not, or need not be, static. The creators of the Shrine gave careful consideration to the meanings it would convey both to the community it represented and to future generations. The exterior buttress groups, for example, embody qualities believed to be worthy of our enduring recognition and adherence: Freedom, Patriotism, Peace and Goodwill and Sacrifice.

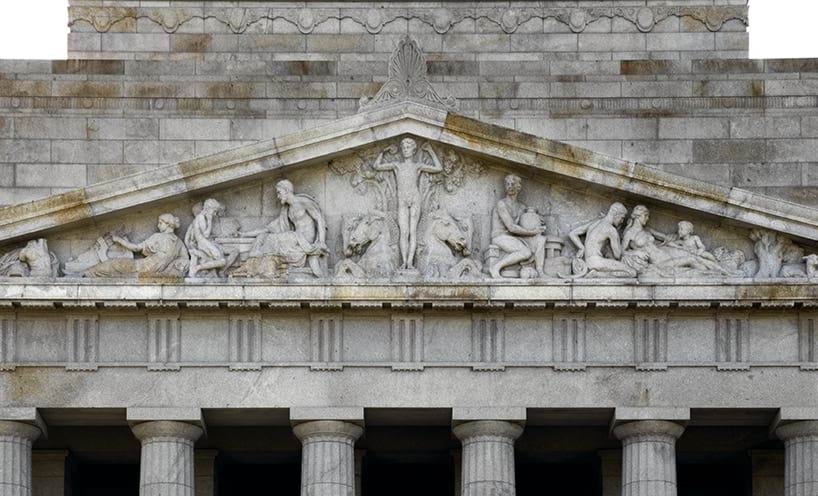

The Shrine was dedicated on 11 November 1934, the anniversary of the day on which the Armistice ended the First World War. The Ray of Light ceremony in the Sanctuary, central to the experience of the Shrine, is a continual reminder of this moment. Significantly this honours the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month and the ascendance of peace over war in 1918. In 1934 the principal entrance to the interior Sanctuary was. from the south. The Anzac Day march progressed along St Kilda Road into Domain Road then entered the southern Reserve. The stone carving above the southern portal represents The Homecoming, the return of Australia’s youth to their country after the war; it portrays young Australia. Older men, who had taken their turn in industry while younger citizens served abroad, hand back their tools. Agriculture is suggested by sheep and fruit trees and elsewhere symbols of education and music evoke civilization and peace.

The Second World War Memorial Forecourt was dedicated in 1954, removing a Pool of Reflection to make way for the parade ground and new processional entrance to the Shrine through the northern portal. This was a practical adjustment that shortened the march and recognised the strength of the visual and physical connections between the Shrine and the city. The change to the Shrine’s main entrance brought to prominence the Call to Arms carving above the north portal which shows young men taking up arms and going to war; a reversal of the intended emphasis of the Shrine’s symbolism, from peace to war, for pilgrims and visitors as they entered the Sanctuary.

In the late 20th century the Shrine Trustees’ appreciation of a continuing need to reassess the Shrine’s relevance, to ensure it remained a vital cultural institution occupying a central place in society, grew from their recognition that most citizens no longer have direct experience of war; that the origins of Australian society are increasingly diverse, reflecting different experiences of war from those in whose memories the Shrine was originally built. In response, the Visitor Centre opened in 2003, flanked by two courtyards to improve access to the inner Shrine. Symbolism in each courtyard reflects the First World War origins of the Shrine. The courtyards reference trenches, the flora of the Mediterranean, and the jetties from which the Australian Imperial Force departed Australia and on which they landed abroad. In the Garden Courtyard, the juxtaposition of light and dark paving, with which the sun’s shadow aligns perfectly at 11am on 11 November, echoes the Ray of Light ceremony.

The Galleries of Remembrance, the full realisation of the Trustees’ vision, were dedicated on Remembrance Day 2014. Two more courtyards completed the symmetry of the Shrine’s design and introduced further symbols of remembrance. A garden of Asian plant species references Australia’s roles in conflict and peacekeeping in our region. The dedicated schools’ entry courtyard is shaded by a large poppy and its walls are embellished with a map of the world. The auditorium is defined by motifs of the crane and dove; international symbols of peace.

The Galleries introduce interpretation in support of the Shrine’s ceremonial activities, providing narratives of Victorian service and sacrifice in war and peacekeeping from the 1850s to the present and a longitudinal view of the changing nature of warfare and peace. Efforts to prevent war and secure peace through increasingly global, multilateral strategies are explored, as are the sacrifices of civilians in conflict and the international nature of war. The stories told aim to illuminate our perspectives on Australia’s roles in conflict and the total impact of wars.

War is personal. The Galleries create an intimate experience for visitors, connecting them as closely as possible to people just like us and all that this implies about our own capabilities for war and peace. Each personal story presented is an act of remembrance, offering an individual perspective on events that defined that person, and imposed terrible suffering, loss of life and grief. The Galleries don’t seek to recreate their experiences but, by using multiple voices, offer contemporary responses that illustrate the grand narratives of war and reveal the participants’ motivations and the extent of their sacrifices.

The Peace Gallery asks whether there are other ways to resolve tension than by conflict. This final gallery presents stories of inspirational change brought about by peaceful means. Peace is no longer simply defined as the absence of war. To maintain peace in our increasingly interconnected world, we need for example, to ensure sound environmental management and strive for economic equity; observe the importance of starting to work towards peace before war’s end, and of having clear objectives as to what we want peace to look like when conflict ends; and accept our responsibility to protect those who are made vulnerable by conflict. These displays recognise that tension is inherent within humanity and that formal and informal efforts for peace, can never cease.

We need to honour those who have sacrificed so much in war and peacekeeping by adhering to the idea of the Shrine as an evolving memorial, giving continuing consideration to the meanings we are conveying to Australians and our international visitors. By understanding our audiences and more actively promoting debate to engage community, the Shrine can contribute to a conversation which looks honestly at war and our successes and failures, to promote understanding of ourselves and our capacity for resolving conflict.

In the Peace Gallery visitors can interact with an electronic peace wall that features the Global Peace Index, updated annually by the Institute for Economics and Peace. The Institute seeks to quantify peace and its benefits, and in so doing, to shift the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable and tangible measure of human wellbeing and progress. In their work, and that of many others which is too infrequently heralded, lie counterpoints to our dark history and the basis for an ongoing conversation that might have appealed to the grieving community who built the Shrine.

Author:

Jean McAuslan was Director Access and Learning at the Shrine of Remembrance. Jean worked at the Australian War Memorial as an art curator before moving into gallery development and leading the project to redevelop the Memorial’s Orientation and Circulation galleries. From 2003–2019, Jean led the Shrine’s special exhibition program and touring exhibitions and led the concept and content development for the Galleries of Remembrance.

Updated