- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

Through interviews, diaries and war service records, discover how three Victorians – each with a unique perspective – experienced the end of the Second World War on the Homefront.

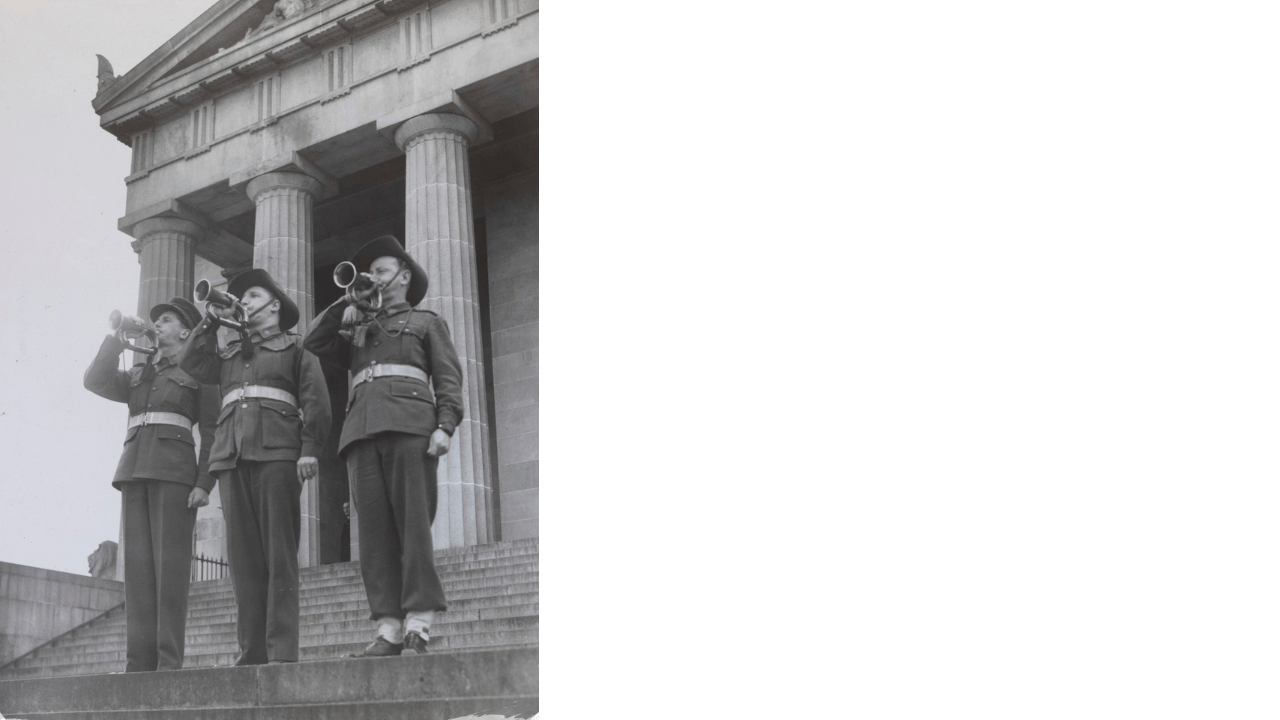

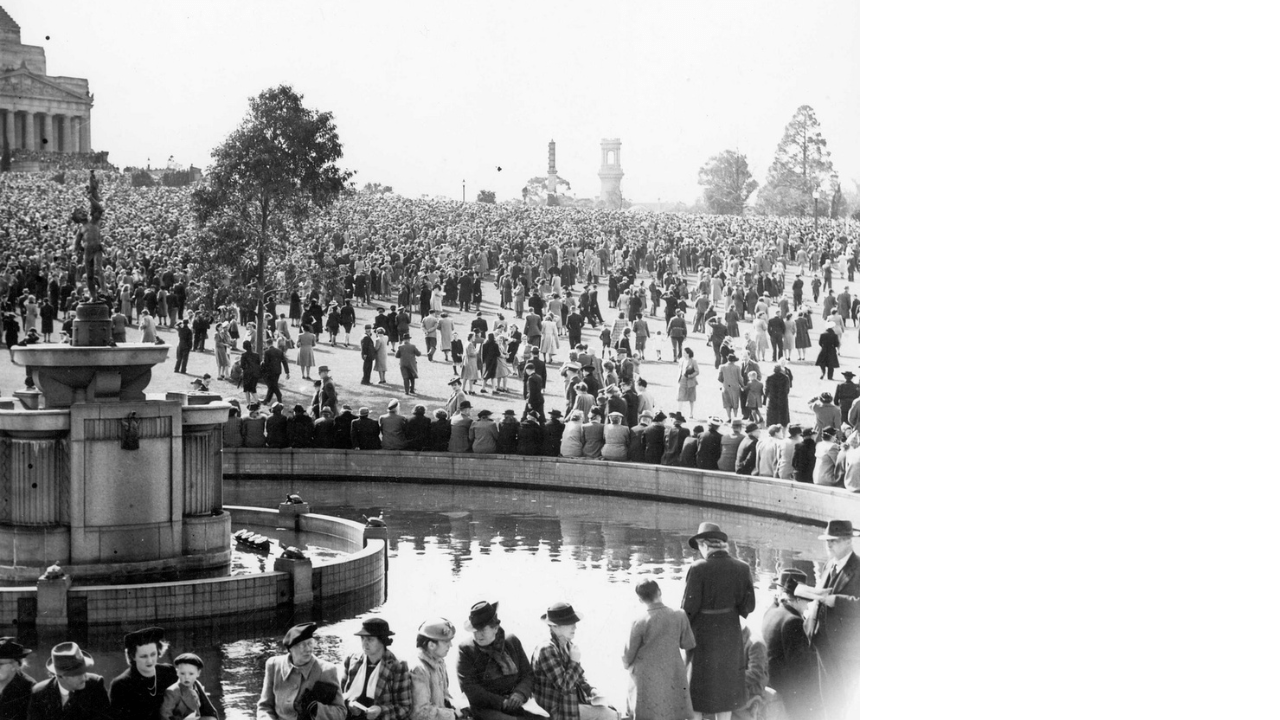

It was a cool morning with light rain in Melbourne on Wednesday 15 August 1945 when Australia’s Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, addressed the nation over the radio.

“Fellow citizens, the war is over… Let us remember those whose lives were given that we may enjoy this glorious moment and may we look forward to a peace which they have won for us…Nothing can fully repay the debt we owe them…”

Newspapers, word of mouth or radio, when the news came through, Australians rejoiced.

As we mark the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, I set out to uncover how the news was received on the home front, including by my father, Alf Argent. For some, it was business as usual. For many, a profound sigh of relief.

Elizabeth Mackenzie

Elizabeth Mackenzie, now a sprightly Centenarian, recalled her wartime service with me in her home in Melbourne. Elizabeth was born in Quarry Hill Bendigo in December 1924 and was working as a legal typist with a Solicitors firm in Bendigo, where she completed the course and training to become a stenographer. When Elizabeth turned 18 in December 1942, she was quite determined she would join the Army, to “travel the world”, proclaiming this much to the protests of her mother. Elizabeth officially enlisted in the Commonwealth Military Forces (CMF) in the Australian Women’s Army Service (A.W.A.S) on 10 August 1943. She explained her desire to travel took her “from Bendigo to Melbourne and back to Bendigo again!”.

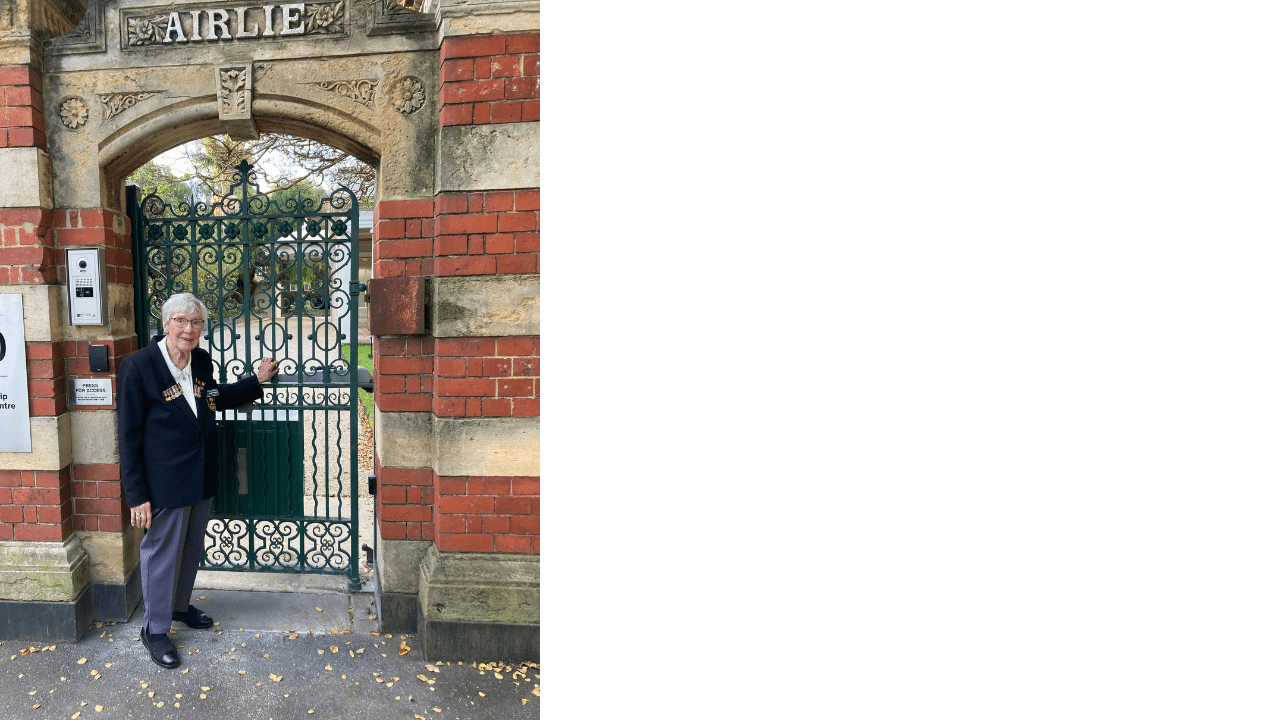

There was training in Bacchus Marsh and at “Camp Pell”, named after Major Floyd Pell, also known as Royal Park. Elizabeth’s first accommodation was a house named “Flete” in Armadale. Later there was an old home called “Harbury”, that Elizabeth referred to as a “women’s barracks”. Harbury House was a stately house in Ackland St, South Yarra, and was the headquarters for the Services Reconnaissance Dept (SRD), which was a military intelligence unit. Elizabeth was also billeted in Elwood to a house named “Fortuna”, with recollections of bicycle and tram commutes, once being fined on a train for being in a first-class area with only a second-class fare! Her Army service soon took an intriguing turn that would change the course of her life. Elizabeth was sent to work at “Airlie” a former private home at the corner of Punt and Domain Road in South Yarra—just up the road from the Shrine of Remembrance.

During the Second World War, “Airlie” was used for planning secret missions including Operation Jaywick, the infamous raid on Singapore Harbour conducted by Z Special operatives. Elizabeth remembers that there was a secret tunnel under Punt Road from Airlie, however, she stated quite clearly there were things that she would never speak about and has kept her word throughout her life. During her time at Airlie, Elizabeth used her typing and secretarial skills, handling personnel files amongst other things, and it was there she met her future husband Gilbert Mackenzie, a Z Special operative.

When news of the end of the Second World War reached Elizabeth in Melbourne, and those still working for the Army back here on the homefront, it really was business as usual. Memos were written, letters typed, personnel files continued to be updated. Elizabeth has only fleeting recollections of the event, but the ethos was that there was still work to do and she did not recall any prolonged celebrations or festivities. Instead, she simply remembers things continuing on as they had. Elizabeth remained in the Army until 19 September 1946 and coming full circle was transferred to the Australian Army Cartographic Company (mapping) back in her hometown of Bendigo.

Elizabeth continues to share her story of service to ensure this time is not forgotten.

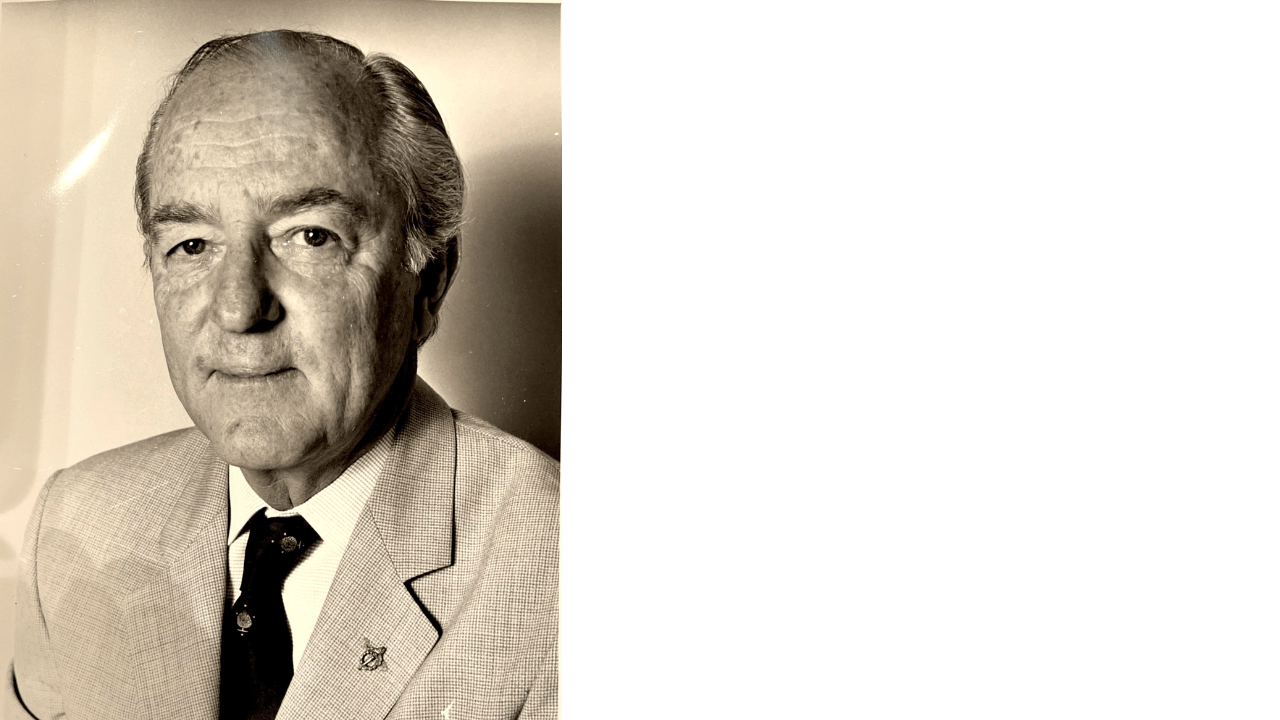

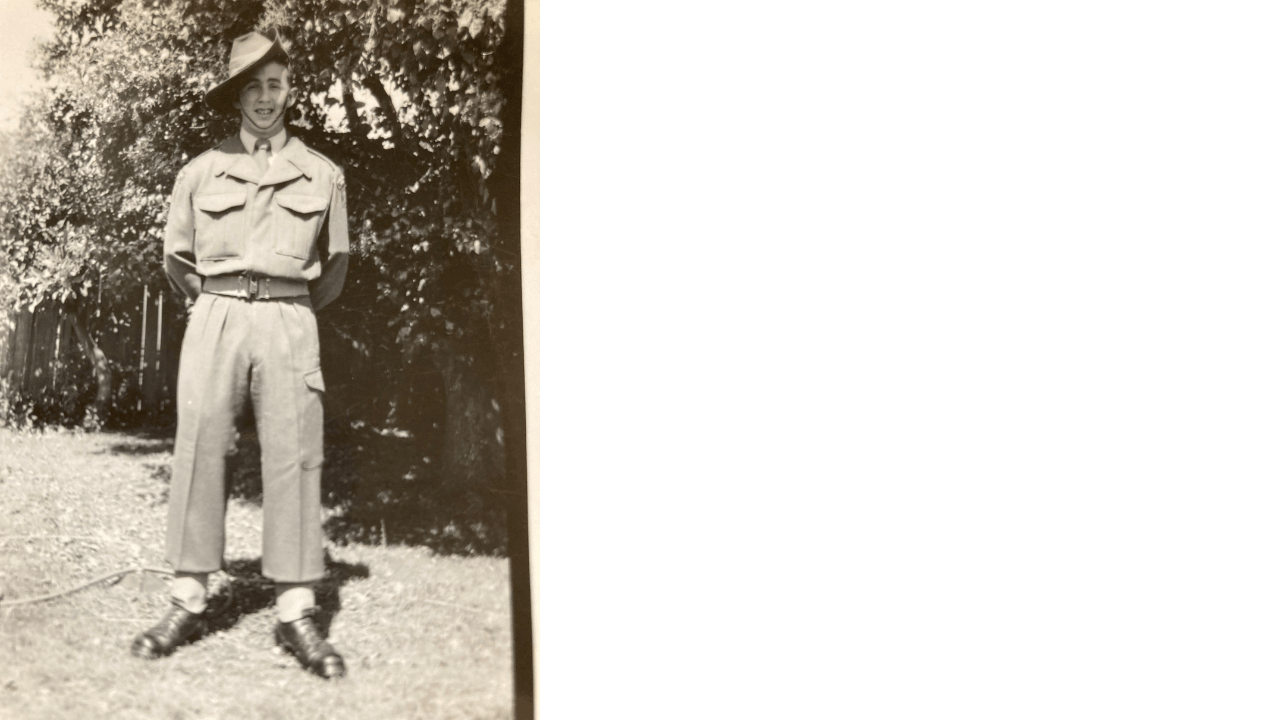

Alf Argent

My father, Alf Argent, was 18 when the announcement came that the war had ended. A country lad born in March 1927 in Lang Lang Southeast Victoria, Alf was the eldest of six and was keen to join the Navy or Airforce in particular. His parents, having lost family in the First World War, were not so keen to bid farewell to their son. There was much mourning for these losses in Alf’s family, a grief that was echoed in households worldwide.

Alf was undeterred and his diaries note he sent in applications to join the Naval reserves and completed the Royal Australian Air Force medical and aptitude examinations. However, the RAAF had a glut of air crew and he awaited “Manpower” directions—wartime instructions from the government telling you where you were needed most. It was suggested Alf join the Army instead, and he eventually enlisted on 29 May 1945

A tram trip from Flinders Street up to Royal Park followed where he was issued with uniforms and identity discs. The next day, 1 June 1945, the recruits travelled by train to Cowra. In his diary notes Alf recalls;

“We arrived at Cowra, in the freezing cold at 01:30 hours, were put into trucks and driven the short distance out of town to the camp; given hard biscuits and cocoa, six blankets and a palliasse; shown empty, unlined corrugated iron huts, each of which held 24 men and told to sleep and be quick and quiet about it. Thus we entered the training machine of the 2nd AIF”.

The training entailed marching, drills, .303 rifle practice, throwing grenades and firing Bren and Owen guns, and training in a gas hut. Sunday afternoons after Chapel provided an opportunity to enjoy a walk, and the nearby Japanese prisoner of war camp, whilst out of bounds, could be viewed in the distance just over three kilometres away.

Alf’s diary recalls:

“On Monday 6 August 1945, we marched out to the Pioneer range and fired our rifles from 100, 200 and 300 yards. My score was 65 out of 75. On the same day, 4830 miles to the north, an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.”

No sooner had it begun for Alf, his diary notes:

“ …15 August 1945, the War was declared over. The siren went off at Brigade hill to celebrate this and I remember men running over the hillsides up there. The War had come to such an abrupt and unexpected end that the only thing the authorities, all the way down the line from Canberra to Cowra, could do was to let things run on as they were”.

The war was over, and whilst there was a sense of relief, there were no jubilant scenes or celebrating as training continued on for the soldiers of A Coy 4 ARBT (Australian Recruit Training Battalion). Alf’s diary does however hint at the uncertainty felt at the time.

“... nobody knew how the Japanese armed forces all around Asia would react to this sudden capitulation”.

Army life on the home front simply continued on.

“On Friday 17 August 1945, I marched out of 4 ARTB with a movement order to the 1 Australian Signals Training Battalion (1 ASTB) Depot at Bonegilla … Much improved food and there was more of it and longer hotter showers”.

After applying and being accepted into Duntroon Military College, Alf was demobilized and discharged. The next day, Friday 22 February 1946, he and 19 others boarded a troop train which would carry them to Duntroon, where they joined other successful candidates. Those who completed the training would become the class of 1948.

Alf Argent would go on to serve 30 years as an Army Officer, mainly with 3RAR, (Royal Australian Regiment). He served with the British Commonwealth Occupied Forces in Japan (BCOF), as Intelligence Officer in Korea, Malaya, Borneo and did three tours of Vietnam. There are several of Alf Argent’s objects on display in the Galleries of Remembrance at the Shrine.

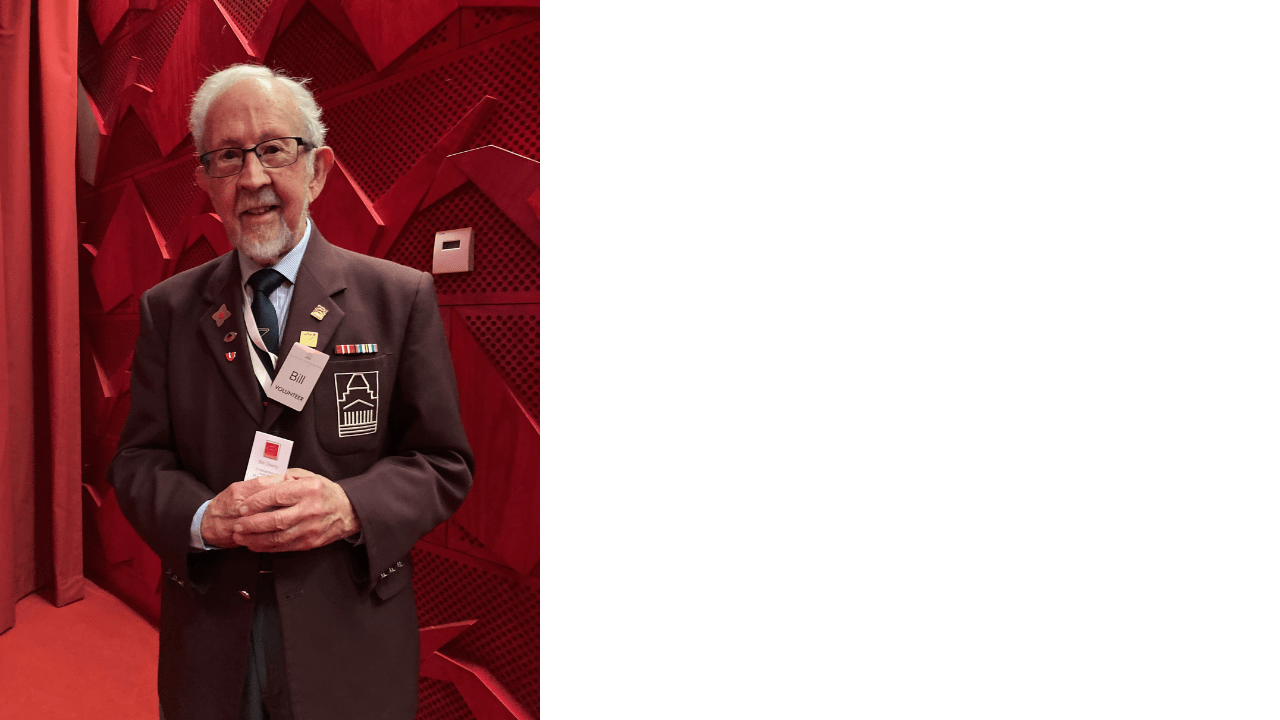

Bill Cherry

Bill Cherry is one of the volunteers here at the Shrine of Remembrance, and he graciously sat and shared his recollections of the end of the Second World War with me. Born in December 1932, Bill was just 12 years old when he heard the news of the end of the Second World War. At the time, he was a student at Brunswick Technical School in Melbourne.

News of the war was daily fodder. Food rationing impacted the family, although Bill recalls no one he knew went hungry, but the same food was often on the menu. There was a slit trench as a shelter from air raids, but Bill said it may have only provided some protection if they could all fit in! With toys in short supply, Bill and his neighbourhood friends made balsa wood model aircrafts.

At school, some of the classes had limited resources and RAAF fitters were trained in the engineering workshops there, which Bill found disappointing as he missed out on such classes. Bill also recalls watching students knotting ropes together to create camouflage nets that were then distributed by the Army to wherever they were needed. He recalls the ropes were hooked onto the drinking bubblers as they were woven together.

Bill was in woodwork class when the announcement came that the war had ended, and he distinctly remembers a teacher coming in saying “it’s all over”.

“There was a school assembly and we went off up Sydney Rd, to the sound of car horns and tram bells.

“In the evening Dad took me into the city to join in the festivities. This turned out to be a very scary experience for me as a 12-year-old, as we were caught up in a surging crowd. Dad managed to squeeze us in behind a tram, which we followed to safety, walking on the tram tracks behind the tram”.

Bill was happy to reach the security of his family home and it was a very overwhelming moment, not just for Bill, but his family too. The war was finally all over, except for the mourning and remembrance of Bill’s family member in the 2/21 Battalion who was first thought to have died of illness, but was actually executed in Ambon. Bill believed the reality of this loss was kept from his mother, but Bill’s older brother thought she probably knew.

At 18, Bill registered for National Service and at 19, he commenced training. He spent 198 days over a three-year period serving the nation, which he enjoyed.

Bill, now 92, still enjoys sharing stories of service and sacrifice with visitors to the Shrine.

My father, Alf Argent, passed away in 2014 and these reflections were drawn from his diaries and earlier conversations he had with me. As a family, we lived in Army Barracks at times and my older brother and I just accepted as normal that Dad was in the Army and my mother worked hard to create a sense of normality. We saw him in uniform and were surrounded by Army staff every day. My Dad, as is true of other Defence personnel, seldom spoke of his service. It wasn’t until later in his life that he would share small snippets of his Army life.

Now, together with Elizabeth and Bill, all have offered an insight into a moment in time that will long be remembered.

Author:

Carolyn Argent is an Education Officer at the Shrine of Remembrance and is Alf Argent’s daughter.

Interested in other Second World War content? Click here.

Learn about volunteering at the Shrine.

Updated