- Conflicts:

- East Timor (1999-2005, 2009), Afghanistan (2001-21), Iraq (2003-2009)

- Service:

- Army

I am a professional Australian infantry soldier. At 50 I have spent nearly the entirety of my adult life in the military. I have amassed the best part of 1,000 days on active service in places such as Afghanistan, Iraq and Timor-Leste, and at least this again in numerous other commitments. My story is not unique.

I, like so many soldiers, have been shot at, blown up, busted and broken; psychologically and cognitively drained; socially dislocated and spiritually and ethically challenged. My family has ridden this unpredictable and emotional rollercoaster alongside me, mostly in silence, and with a resolve that broadly goes unnoticed.

Additionally, there have been ethical tensions to resolve between warfighting and modern social values. Australia can be a challenging place to pursue a profession of arms: our controversial involvement in Iraq and being warned against wearing uniform in public are examples of this. If you accept my position then you might understand why many soldiers might agree that ‘being away is like being at home and being at home is like being away.

’Now, you may imagine me to be a quintessential ‘warrior soldier’ type. Strong, tall, striking. Forged and hardened in the heat of combat, dark and contemplative, with an air of control and decisiveness, perhaps looking back over his shoulder?! This is true of many I have served with, but not so for me. I am skinny, a little anxious and easily distracted. And my journey too has been different, less about combat and courage, and more about adventure and determination. I will be contented to look back on my life as a professional soldier and be remembered as a humble soldier who pulled his weight to leave the world better than he found it. As a soldier whose sense of history has allowed him to smell the roses and lead an ‘examined’ life.

And so cricket almost accidently became a scaffold for my journey and experiences, providing a purpose when there seemed little; an escape when needed; a conversation when silence needed breaking. It also provided a therapeutic release between deployments as I built a career with the Applecross Cricket Club and the Backyard Cricket Club and the ‘real’ MCG I built in my own backyard. Whether on or in-between deployments, cricket provided a harbour of resilience and communication, of humour and social interaction, and ultimately would even transcend death.

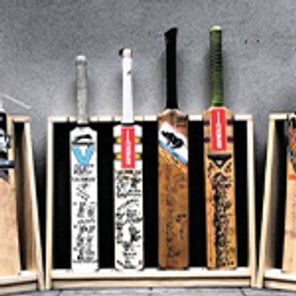

It was my habit to carry a cricket bat and balls wherever we deployed. For me, this odd collection of cricket bats embodies, not so much the courage and combat, but the fear, humour and the humanity of modern warfare. They are the physical and psychological manifestation of the entirety of soldiering, in which ‘combat’ occurs infrequently. The insanity, tragedy and comedy, the sublime and surreal.

The bats hold the signatures of many soldiers who have served, fought and died with me along the way. And when opportunity presented, other prominent people were eager to sign them as well, including members of the British royal family.

Perhaps my favourite signatories are from the 2006 Timor-Leste deployment during which I secured the autographs of key political figures Xanana Gusmão, Mari Alkatiri, José Ramos-Horta and Alfredo Reinado. remarkably, Messrs Horta and reinado are on the same bat only centimetres apart. remarkable because less than two years later Reinado and some rebels came down out of the hills and very nearly killed Mr Horta at home. Reinado was killed during this attempt.

I was, I believe, lucky to have spent time with Alfredo at his Timorese mountain hideout, spending days exercising, playing guitar and cricket. We used these games as opportunities to collect intelligence and conduct soft diplomacy. On occasion he and I would sit on the veranda of the beautiful old Portuguese manor, overlooking the villages and valleys of the Timor highlands, drinking wine and smoking cigarettes till the early hours. I found him an intelligent and charming family man. We talked of the troubles, politics, family and the profession of arms. I enjoyed these times in which we grew to be friends. But there was an unspoken reality underlying our discussions.

At one point Alfredo remarked to me, ‘you have come here to kill me haven’t you?’ (I assume he, like me, slept with a pistol under his pillow during our time together). However, he was not talking to me directly; rather, he understood the Australian presence indicated that a ‘resolution’ was nearer. And given the enemies he had made this was likely to include his demise. racked by excessive drinking, paranoia after several attempts on his life and frustrated by his perception of the corrupt system, in early 2008, in the hours before dawn Alfredo and a small group of rebels ventured down from their mountain refuge. Their objective remains unclear but the alleged assassination attempt left President José Ramos-Horta seriously wounded and Alfredo Reinado dead. We landed once again in Timor-Leste hours later and wondered, ‘what if I had spoken with him?’

Each bat tells many such stories and offers insights into the ambiguous and unpredictable operating environs of a soldier where friends one moment can be adversaries the next. Some bats were at the centre of direct communications with enemy combatants in dangerous territory. On occasion Al Qaeda and Taliban commanders (through interpreters using Motorola radios) were heard commenting on our prowess with the cricket bat and ball as they observed us from the valley heights. We invited them to a game of cricket, and to fight. They declined.

All the bats have been outside the wire on operations, one having been Wounded-In-Action. Several have completed military freefall jumps, cheekily disguised as weapons. Such ‘jumps’ are about the most technically, physically and psychologically demanding skill I have learned—especially those that included combat equipment, on foreign drop-zones, high in the mountains at night. Being a team member was challenging enough, but to design, plan and lead the execution obviously adds an extra dimension of gravity and fatigue. Luckily, I have had some exceptional people around me who have made it look easy-ish.

On one occasion, having exited the aircraft and deployed my canopy, I turned, as briefed, to the west and away from the moon. I looked to the north, adjusted my night vision goggles (NVGs) and looked up a perfect stack of nineteen neatly deployed canopies at about two o’clock high and hundreds of metres above me. The moonlight was such that I could clearly count each canopy, dramatically set against the snow-capped mountains and a brilliant sparkling night sky, all under the green glow of my NVGs. It was one of the most magnificent sights I have ever witnessed. Mesmerised, I wished for a camera for all of five seconds or so, to be snapped out of it by the need to start leading in the team, ‘that’s me turning north in 3 2 1... the moon is high and to my slight right, heading north at 3,000 feet, turning east in 3 2 1...’Make sure you smell the roses.

However, the bats also provide contrast for me. It didn’t occur to me until later in my career that my family did not share my joy in cricket. For them, my preoccupation with cricket had kept me away from my precious family time on occasion; a selfishness for which I now feel embarrassed and guilty. My perception, hidden behind the ‘work hard play hard’ excuse of a former age, had twisted my position as a respected veteran in justifying my ‘down time.’ I had arrogantly prioritised such recreation time above that of my wife and family. I now know they suffered in silence, and I have since evolved to recognise the roots of the veteran-victim archetype that too many, including me, leverage.

My wife, like the rest of my family, was a war and cricket widow of sorts, and essentially raised our family by herself over nearly two decades. It is a great understatement to say I am profoundly indebted to her service to our family, and nation for that matter. Her ability to keep the nucleus of our family grounded and functioning is testament and a great exemplar of the life that all soldiers’ partners and families endure. I am grateful and proud that we have been lucky enough to have made it, so far. These stressors are in many cases too much for wives to bear, and marriages break down often. Equally, the significant impacts of service on children are often left unexamined.

Now my family and I are transitioning into civilian life, the bats have become a lens through which we reflect on our journey. Our future feels forbidding and uncertain, as it is for many soldiers.

Through my journey in studying philosophy and psychology to explore the ethical and moral implications of combat, leading to becoming a registered psychologist, I strongly believe, and advocate, that through-life education for our soldiers is a large part of the answer to this successful transition, to help them help themselves. We will all benefit from a soldier’s continued contribution to our society and nation. And this is critical to a soldier’s identity, as being a professional soldier is not just a job. It is a higher calling and commitment to society in which we somewhat ‘exchange our human rights to become instruments of military and political objectives.’ But somehow, our soldiers are too often portrayed as damaged or as victims, often by a media and bureaucracy preoccupied with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. We must disenthrall ourselves from this stereotype to understand the majority are not suffering. As a psychologist I acknowledge and work with those who are suffering. But I contend that they are the minority, and that it is this perception that is actually most harmful.

The majority of us are ordinary humans who have had a unique yet constructive and inspiring experience, and in elevating this perspective I believe we will help all soldiers. This collection of bats conjures many stories of courage, combat, fear, humour and adventure, and remains a respectful dedication to all of those who have fallen in their journeys. The bats, like those people embodied in them, look exhausted and tattered after a long period of conflict. And if I have learned anything at all over this journey it is that in life, as in cricket, one must sometimes be on the attack and sometimes in defence. The art is not only in knowing which shot to play and when, but also when to stop and smell the roses in the garden of life.

Good cricket to all.

All images courtesy of Sergeant H.

Updated