- Services:

- Army, Air Force, Navy, Nursing services, Women’s organisations

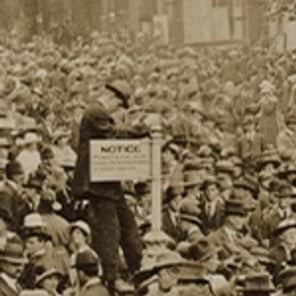

The spontaneous revelries brought cities to a standstill. Crowds took over the streets in celebration. But was celebration and exultation all that their presence on the streets meant? A closer look at responses to the announcement of the Armistice suggests that the public outpouring of emotion was as much a response to the relief from years of anxiety, fear and longing that finally promised to come to an end.

In November 1918 Australians had been anticipating the end of the war for several weeks, as news from the major fronts in Europe and the Middle East had steadily improved. But there were two sentiments alive in the Australian community as they waited for news. Excitement at the prospect of victory over Germany was certainly one of them; the other was an ongoing anxiety surrounding loved ones still at the front. For more than four years the war at home had pressed itself into Australians’ minds, and in late 1918 it was no less potent. Anticipation of the war’s end was less about imminent victory than it was about having loved ones safe. This was the vein in which Sydney woman Isabella Parkes watched for news, as she worried for her son:

War news is almost too good to be true—but peace is in sight we are told. When will you be coming marching home laddie?

The experience of wartime anxiety centred on those at the front. But for those who felt that anxiety daily, its effects were repressive and debilitating. Some worried that their health was so impacted that they might not live to see their men return. The end of the war promised not only the preservation of family and friends in the Australian Imperial Force but relief from one’s own apprehensions. When Joyce Byrne in rural New South Wales began to believe that the war might actually end, her motives were clear enough:

What heaven if it does. Everybody is so tired of it.

In Perth at the same time, Ada Benjamin declared to General Sir John Monash that, despite false starts, she expected the end of the war soon. ‘It has been long enough now’.

Such were the emotions that fuelled anticipation. As an armistice became imminent, officials began to fear that news of the event would be met by the same kind of riotous excesses in Australian cities that followed the relief of Mafeking during the Boer War. New South Wales Premier William Holman hoped to head off that kind of behaviour as he proposed a standard form of ceremony across the country, involving ‘sober jubilation’. Sobriety was also the keynote for those who hoped to have liquor bars closed during celebrations, though others like Victorian farmer Jim Glowrey told his father:

The war news looks very bright and should help to improve hotel business a little.

Rumours that the Armistice had been secured swirled about persistently. In Sydney, premature reports provoked a major outbreak, five days before the official announcement. The news spread largely by virtue of sound: locomotive whistles up and down the lines, ferries in the harbour and then the crowd itself brought other people into the streets. Factory and shop workers walked out, obliging their employers to close for the day, while others emerged from their homes and headed into the city centre.

The social reformer Jessie Street found the streets jammed and the noise extraordinary:

every second person had a hooter, bell, rattle, whistle, or some other instrument—were working it for all they were worth. Kerosene tins were never so popular before.

One returned soldier declared the ‘dreadful row’ was ‘as bad as being at the front whilst a big bombardment was on.’ Bands in Martin Place encouraged the singing of popular and patriotic songs, while all variety of conveyances provided joy rides. In an attempt to describe the scene, William Jones asked his son:

Did you ever see an entire city go mad? That is what happened on Friday last.

Days later the scenes were repeated in the other major cities. In Brisbane, one correspondent described the crowds’ emergence in the streets, ‘as though an ant-bed had been aroused’. In Hobart, Edwin Bean estimated for his son Charles that ‘the whole, or almost the whole, of Hobart[’s] population ... filled the main thoroughfare.’ ‘Melbourne went mad yesterday’, Annie Crowther told her nephew, ‘it was a marvellous sight.’ Lady Margaret Stanley, whose husband was Governor of Victoria, had expected the crowds to misbehave, but she was surprised to find them more good-tempered as they:

surged and roared through the streets, bursting into songs and hymns and cheerings at intervals.

The good nature of the crowds was noted widely, in what the poet John Le Gay Brereton described as a ‘democratic friendliness’; Jessie Street insisted:

it really did you good to see everybody so simply bursting with happiness elderly and staid men and women, grandparents ... radiating benevolence and sincerity at everyone.

One had never seen Sydney, Brereton declared:

spontaneously abandon its self-control and riot good-humouredly in spite of the warnings of authority and official contradiction of the news which started the fun.

Such scenes suggest the thrill and achievement of victory. But the reality was much more complex. Here was the first opportunity to cast off some of the restraint that had characterised the war years, much of it self-imposed, or socially dictated in the face of so much anxiety and loss. As Jacoba Palstra would put it to her son, the Christmas that followed the Armistice represented ‘the first time in years that one dared to be happy and show it too.’ Palstra’s reticence was based not only on a consideration for others in their suffering: she had two of her own sons serving in France and well understood what it had meant to endure the war and its precarious line between hope and the desolation of grief. In the moment of victory that problem could be suspended but it demanded recognition.

While Brereton had seen in the crowd good humour, he was also sensitive to what he called the ‘deep feeling’ of the event in Sydney. Specifically, he meant:

the relief which had to express itself or burst, and the tense undermood of sorrow for what could be no more. Tears and laughter struggled for pre-eminence in that great day.

Like Brereton, William Jones had seen in the Armistice celebrations the opportunity to express the feelings that had been so restrained by the war. ‘In less than an hour’, he mused the following day, ‘the pent up feeling of four years was let loose’. Jones understood the array of feelings that were let loose; his son had been fighting on the Western Front, and indeed the anxiety of waiting for news had eroded his health to the point of a nervous breakdown soon after the Armistice. The relief to which he had referred, however, was felt widely in the community. In Melbourne, Harold Walker reported the ‘wonderful feeling of relief’ induced by the Armistice, together with the:

heartfelt gratitude at the thought that the awful risks of war have, at all events for the time, ceased to threaten so many of our own dear friends.

The Armistice eased emotional restraint in the community and thoughts turned quickly to when loved ones might begin returning home. At the same time, however, there were many who felt awkward about their own relief from the war’s torment. They were thinking of those for whom the Armistice eased nothing of their pain but rather increased their awareness that the war had cost them the lives of their own loved ones. rose Keast of Broken Hill had suffered terrible anxiety over her son, on service in France and then Mesopotamia. She found in the Armistice ‘a much lighter heart’. And yet she was all too aware of those whose loved ones would not be returning. ‘After my joy’, she told her son:

I begun to think what this terrible war meant to some just think of the poor mothers that have lost their all there what all this blowing of whistles and ringing bells meant to them it would only make them feel their sorrow more.

Lady Margaret Stanley felt similarly:

we have hardly the right to rejoice that our Bill and Oliver and Anthony have all come through it, when so many homes have been emptied.

For their part, some of the bereaved found vindication for their sacrifice in the Armistice. In Melbourne, Reuben Hallenstein declared it:

a great consolation to even those of us who have lost our dear ones to know that the sacrifice has not been in vain.

But there were others too, who found the Armistice a painful affirmation that their loved ones were not returning, and that the war had robbed them of the future they had anticipated. Arthur Fry had lost two sons to the war. The day of the Armistice, he insisted:

was the saddest day I have passed for a long time—the great victory seems to mean so little for me, which to the great bulk of people was so joyful.

The ‘buffoonery’ of the celebrations ‘hurt a bit’, he said, though he understood the need.

The divisive politics of the war were also much in evidence at the very moment it ended. In the federal parliament, the antipathies surrounding the conscription issue were still playing out even as senators were offering thanks for the victory. In the streets too, those tensions were being felt, as participants divided fellow citizens into those who deserved and those who didn’t deserve to enjoy the relief and release of the end of the war. Ada Jones told her son:

those that made the most noise, was the fellows who stayed at home, the returned men as a whole took things very quiet.

Jones probably was not in a position to appreciate that even those who determinedly opposed war could share her sense of relief at its end. yet the sentiment was certainly shared. Brisbane labour activist Margaret Thorp, for instance, thought that the cessation of hostilities was ‘wonderful news’ that would mean ‘a gloriously happy Xmas for everybody.’ Lil Farrell in Melbourne also felt ‘so happy today to think the war is over’, though she was not so overwhelmed as to parade the streets in patriotic garb. In Sydney, Mary Boote joined in ringing bells and blowing whistles, though she too distinguished herself from those she saw giving in to patriotic excess by insisting that ‘we’re rejoicing because the guns have at last stopped belching murder.’

Just as news of the Armistice drew a multitude of people into Australian streets in November 1918, so were their responses to the end of the war much more complex than the joyful faces appearing in the illustrated papers suggested. As much as the Armistice was the instrument of victory over Germany, it was also the sign that a long confrontation with fear and anxiety in Australia was coming to an end.

Where that war had so often been fought in the seclusion of private homes, or in small supportive groups, the Armistice brought those people into public to express their relief and to begin to expend what one observer called ‘the war-strickened-nervous energy of the people.’ The authorities had feared riot and larrikin violence; instead, that first Armistice Day in Australia revealed just how deeply the war had become part of everyday existence and the profound relief Australians felt that its presence might soon begin to recede.

Author

Dr Bart Ziino teaches history in Deakin University’s School of Humanities and Social Sciences. He has written widely on private experiences of the First World War, commemoration and memorialisation. He is author of A Distant Grief: Australians, War Graves and the Great War, and editor of the volume Remembering the First World War.

Updated