- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

- Service:

- Army

My father-in-law Tom Barnes parachuted into Greece in October 1942 for sabotage activities under the auspices of the British Special Operations Executive. It was one of those operations that was meant to be ‘in and out before Christmas’, but as it was, Tom stayed in Greece until April 1945. He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and became one of two Area Commanders for the Allied Military Mission to Greece (AMM). For his service he was awarded the DSO, MC and MID.

Tom was a Kiwi, but he’d been working in Australia as a civil engineer since 1939, following an eventful year in New Guinea as a surveyor where he first started the habit of daily diary-keeping that he continued for the rest of his life. He joined up first with the 2nd Australian Imperial Force but obtained leave for the duration to join the New Zealand Engineers. After the war he returned to Australia, married his Australian fiancée, worked in Tasmania and then Victoria as a civil engineer.

Tom’s wife Beth preserved his war diaries until her death in 1995, when they passed to their son and my husband Chris. As I read them, I was astonished at the relentless pace of events for members of the Allied Military Mission to Greece (AMM): bridges to be blown, pursuits and escapes, troubles with the rival resistance organisations, civil war—at one point Tom’s headquarters had to flee attack from the left-wing resistance organisation Greek People’s Liberation Army (ELAS)—and the Germans, who naturally had embraced the opportunities the civil war provided.

In September 1944, Tom got a call about a top-secret job. He had just finished working on a new harbour in Transjordan and was in Cairo, somewhat jealous of the action that engineers with the New Zealand Division were seeing and trying for an opportunity to join them. This new job wouldn’t be exactly what he hoped for but sounded exciting: a sabotage operation behind enemy lines in Greece. The target was one of three bridges on the railway line running down the east coast of Greece supplying Rommel’s army in North Africa. Naturally he didn’t find out the details of Operation Harling until after he’d agreed to take it on.

He landed with a team of 12 in Greece: three engineers, three interpreters, three wireless operators and three in command. Of the three possible targets, all reasonably close together on the line south of Lamia, near Brallos Pass, they were to choose the most feasible. With such a small party, they would need the assistance of local resistance fighters, known as andartes. Unfortunately, British intelligence about the numbers and location of these groups was unreliable to say the least.

The matter was urgent, with the battle of El Alamein not far in the future. Parachute training was normally two weeks but in this case one day had to suffice. Three teams of four set out expectantly in modified Liberator aircraft but the drop was aborted. Local resistance fighters were meant to have laid out signal fires, but none could be seen.

The aircraft had to be serviced before another attempt was made. They set off again on 30 September. This time two of the aircraft made it. The third turned back.

The message telling them where to land had been garbled. They should have landed much further to the west, where General Napoleon Zervas was leading a group of largely republican andartes and where no doubt signal fires had been laid out as arranged. Instead, they landed on the precipitous slopes of Mount Giona far to the east. The signals they thought they had seen belonged to shepherds, not andartes.

Danger was everywhere. This area of Greece was occupied by Italian soldiers, doubly galling for the Greeks who had roundly beaten the Italian army in the mountains of northern Greece and Albania before the Germans had arrived in force in April 1941. Fearing betrayal, the party moved to a mountain cave where they spent six weeks moulding explosives for the operation and sleeping in cramped conditions. Their survival is probably owed to ‘Barba Niko’, a local Greek who had formerly lived in the United States and took over responsibility for their care and sustenance. He organised food and help from the local village of Stromi and found them safe refuge when word came that the Italians were in pursuit.

It proved almost impossible to contact the leader of the local group of andartes, Aris Velouchiotis. Eventually the leader of Operation Harling, Brigadier Eddie Myers, sent his second-in-command, Colonel Chris Woodhouse, on a nineteen-day expedition across the mountains of central Greece and back to seek the support of General Zervas at his andartes headquarters in the Pindos mountains. Returning triumphantly with Zervas and his men, Woodhouse finally met with Velouchiotis and secured his support as well. With Velouchiotis they found the third group of the Harling party, who had landed a month later than the others, dropped close to an Italian outpost and had been with Velouchiotis since shortly after their arrival. A notable member of that group and its leader was Themis Marinos, the only Greek member of the Harling party, who died in December 2018 just short of his 102nd birthday.

An Italian garrison held both ends of the Gorgopotamos viaduct, the bridge finally selected as the only feasible target for the operation. On the night of 25 November, the 12 Allied soldiers and around 100 resistance fighters, all under Zervas’s command, along with a group of mules carrying 400 pounds of plastic high explosive, crept down the side of Mount Oiti to their forward rendezvous at the Gorgopotamos River. Tom’s diary entry for that day gives a graphic description:

Whole gang with mules—it was dark as pitch & the going bloody. —The plan is for my D [demolition] party to wait until the Bridge is clear & then go in. Zero hour is 2300—The trip down was done in absolute darkness & silence—we crossed the river and were on our own—off loaded the mules—and proceeded to our rendezvous—got there @ 23.10—firing 23.15—bullets hit around us but OK... MMGs [medium machine guns] LMGs [light machine guns] rifles. T guns [Tommy guns]and Grenades—No Verey signals so went in @ 0015... proceeded to Br. [bridge]—had to cut through wire twice. –Piers not as expected—U shape—Arthur, Inder and I [Arthur and Inder are the other engineers]laid charges & on the X [cross]members—this took nearly an hour—6 main charges & 16 small—Arthur & I finished simultaneously [.] Shooting, MGs, TGs, Grenades, going off all around—3 whistles—cover—terrific bang—2 spans down—one twisted—pier still stood—twisted and leaning. & 10-12’ shorter. —went back—most of helpers cleared off—laid charges on front of D. [demolished] pier & on T members of back dropped span and P on p [pier] next to abutment...Br w[as] held f 3 hrs. ...successful—Proceeded uphill to rendezvous—all hands just about all in...Helluva climb up to rendezvous. Wonderful weather for operation—raining & heavy fog all the time...Halted @ rendezvous—damned tired—everyone too tired to be elated over success of job...we had been 24 ½ hrs on our feet [spelling and punctuation as original].

As the diary notes, Tom and his party got a terrible shock when they arrived under the bridge to lay their charges. The bridge had seven piers constructed of masonry and three of metal. These metal piers were their target. They had received intelligence that the cross-section of the girders was L-shaped but in fact it was U-shaped. The intention had been for Tom to take his party in when the garrisons at both ends of the bridge had been subdued, but the Italians seemed to have had forewarning of the attack, which took much longer than expected. Tom had to take his party in under fire, and it was under those conditions that he had to recalculate all the charges in his head, get his party of engineers and assistants to take all the pre-formed charges to pieces, before setting them in place to match the actual cross-section. A second set of charges were laid after the first explosion, to ensure that the bridge would not be quickly or easily repaired.

After the attack the party had a 2,000 feet climb up the slopes of Mount Oiti to their rear rendezvous. Fortunately for them, low fog covered their escape route from Italian pursuers.

With very little time for rest, the party set out for Zervas’s headquarters in the Pindos mountains. From there they, apart from the four who were to remain in Greece, set out for a submarine rendezvous on the west coast. The operation had been a success, but their activities in Greece were only just beginning.

Tom Barnes took part in two more major sabotage operations in Greece. It is perhaps not well-known that when plans were underway for the Sicily landings in mid-1943, a set of coordinated sabotage operations were carried out in Greece to make Hitler believe that the landings would take place there. This was Operation Animals, and Tom coordinated operations in the north-west region of Greece (Epirus), personally carrying out attacks on a number of bridges.

For one of the attacks, he used a German bomb which had been used a month or two earlier to attack a headquarters village of the local andartes. As the occupation was ending, Tom’s third major operation Noah’s Ark saw the now strong and highly trained andartes sabotaging the German troops who fled north through Epirus. It was then that General Hubert von Lanz, the Commanding Officer for German forces in northern Greece and Albania, made surrender overtures to Tom as Area Commander for the AMM.

At his death, Tom left behind what is now a significant archive. In addition to over 1,000 photos there are maps of Greece printed on silk, compasses concealed in military buttons, his war diaries and decorations, his reports and letters to his fiancée, even some of his uniforms.

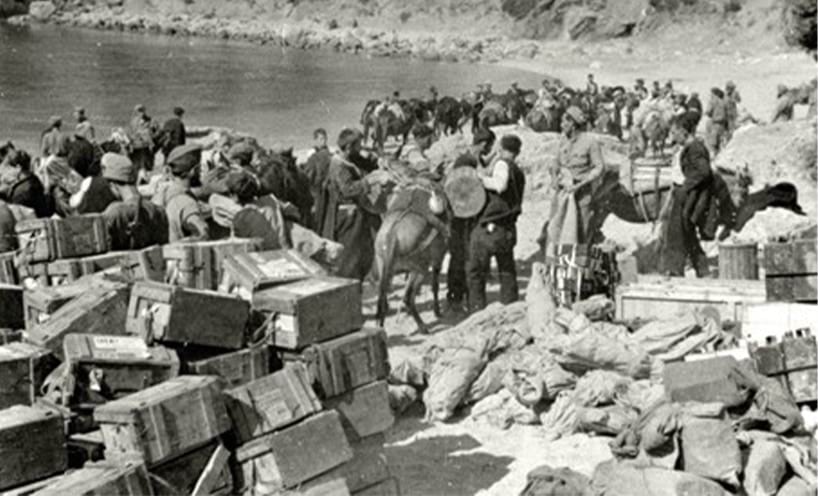

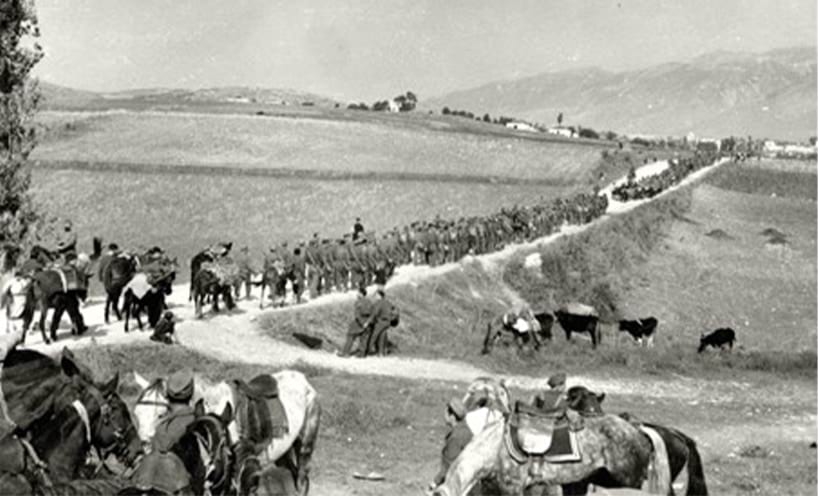

Among the photos is a sequence taken in early 1944 showing boxes of ammunition and other supplies arriving from Italy. They were unloaded on the beach at Alonaki Bay before being loaded onto mules or carried up the hill, and then the whole convoy moving inland. We still have the moving letter General Napoleon Zervas wrote on 8 August 1952 to Beth Barnes when he heard of Tom’s death. In his words:

He was an outstanding figure for all of us and we feel that Tom is not dead. He lives as a symbol of the ideal man and brave soldier.

Tom Barnes was for Greece a second Lord Byron and the whole Nation has admired his heroism and is grateful for his love for our country.

His name will be written among the names of the heroes of the [Second] World War.

All images courtesy of the Tom Barnes photo archive.

Author

Dr Katherine Barnes is a prize-winning author whose most recent book, The Sabotage Diaries (HarperCollins) 2015, tells the story of her father-in-law Tom Barnes’s service behind enemy lines in Greece in the Second World War drawn from his wartime diaries. Formerly a teacher and university lecturer, she lives in Canberra and is a Commonwealth public servant.

Updated