Young Australian teacher Bruce Dowding arrived in Paris in 1938, planning only to improve his understanding of French language and culture. After the war broke out, Dowding helped exfiltrate hundreds of Allied servicemen from occupied France. He eventually paid the ultimate price and was beheaded by the Nazis just after his 29th birthday in 1943.

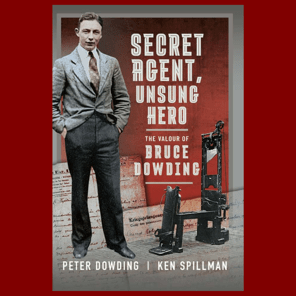

His story is told in the book Secret Agent, Unsung Hero, written by Bruce’s nephew, prominent Australian lawyer and former Western Australian Premier Peter Dowding and historian Ken Spillman.

This podcast was recorded live at the Secreat Agent, Unsung Hero book talk at the Shrine of Remembrance.

Vodcast

Music

Maturity by Solitude

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance embraces the diversity of our community and acknowledges the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation as the traditional custodians of the land on which we honour Australian Defence Force service and sacrifice. We pay our respects to elder's past and present. Welcome to the Shrine of Remembrance podcast. My name is Laura Thomas and I'm the production coordinator here at the Shrine. In this episode, we're taking you to an event that was held at the Shrine in August 2023, where former Premier of Western Australia Peter Dowding, told the story of his book Secret Agent, Unsung Hero. The book was co-written by Ken Spillman, and it follows the fascinating and tragic story of Bruce Dowding, who was Peter's uncle. In 1938, Bruce arrived in Paris with a plan to improve his understanding of the French language and culture. What followed was unexpected, to say the least with Bruce becoming a leader in escape and evasion during the Second World War, and helping exfiltrate hundreds of allied servicemen from occupied France. Like so many other young men, Bruce eventually paid the ultimate price. We pick up here with Shrine of Remembrance CEO Dean Lee opening the event.

DEAN LEE: Good evening, everybody, and welcome to the Shrine of Remembrance. As you would expect for an institution which is somewhat related to the military, we are on time. My name is Dean Lee, and I am serving as the Chief Executive Officer of this place of remembrance. And it's my delightful pleasure to welcome you here this evening for this fabulous presentation that we're about to receive. This Shrine of Remembrance is held in care by the Shrine trustees. On behalf of all Victorians and all Australians, I would like to warmly welcome and acknowledge any current or former serving members of the Australian Defence Force, and also acknowledge the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation as the traditional custodians of the land on which we gather.

This evening, and it's fabulous to see such a crowd on a beautiful Melbourne evening. Lovely almost spring, isn't it? We're here to hear the fascinating story of Bruce Dowding, who in 1938 arrived in Paris with a plan to improve his understanding of French language and French culture. And any of you who saw the article in The Age will have seen this dapper young man who's also featured on the cover of the book that we see here. Bruce's story of course, is extraordinary, but also tragic. And I think that's a poignant reminder of many of the experiences of people at that time in wartime Europe. Like so many men, Bruce eventually paid the ultimate price for his activities, aiding and assisting to exfiltrate prisoners and escapees from the Second World War, mainly allied servicemen. Stories of this nature are always moving, but perhaps never more so when they're told by a family member. And this story of Bruce is told by his nephew, lawyer and former Western Australian Premier, Peter Dowding. In this book, of course, was co authored and written with Ken Spillman. I was just having a pleasant chat with Ken, about his experiences immersed in telling this story. Before we invite our speakers to come forward, I would like to invite Phillip Powell to say a few words. And Phillip is an Honorary Fellow of Wesley College. And Wesley College has a strong relationship to this place. But perhaps even a stronger relationship to this evening story for Bruce Dowding, as some of you will know, was a former student of Wesley, and also teacher at Wesley. So in our Galleries of Remembrance, beneath the building, the Galleries of Remembrance, we hold a Victoria Cross, the highest honour given in the British Empire, for valourous service in conflict, that VC belongs to First World War veteran Captain Robert Grieve, who was of course a student of Wesley as well, and we've been entrusted with its care and display and the relating of the stories of Robert Grieve for nearly 20 years, which we're very grateful. So I'd like to invite Philip to come forward and say a few words Thank you.

PHILIP POWELL: Thank you, Dean. Bruce Dowding is one of the 308 former students of Wesley College who have died on military service. From the shores of Gallipoli to the jungles of Vietnam. Bruce's story along with others has not been forgotten by later generations, Wesley has an ethos of grateful remembrance, which is physically represented in the likes of memorials, plaques, and stories passed down on ANZAC Day assemblies. As a former student, and teacher, Bruce was well known to the Wesley College community of the 1930s and the 1940s. He was a keen sportsman, played in both the first football and cricket teams, and while studying for his teacher qualifications, he commenced a part time position at the school, teaching French to the young boys in the junior school and commenced full time teaching in 1935. In '36 and '37, he was also a member of the collegians premiership football team. The book co authored by Geoffrey Blainey for the 1966 Centenary of the college, succinctly summarised Bruce's World War Two story - 'Gallant little Bruce Dowding. Prep Master on exchange teaching France in 1939, who joined the British Expeditionary Force was captured in France, escaped from a German prison camp, joined an underground unit which smuggled escapees and grounded airmen out of occupied France and who was betrayed by the Gestapo and executed. Last week, a 90-year-old former student told me of his memories of the Junior School Headmaster providing updates to the students on what was the latest news on “Mr Dowding” He recalls the last was to advise “we regret that it has been notified that Mr Dowding has lost his life in France - he will be fondly remembered” Wesley College thanks Peter Dowding and Ken Spillman for their diligence in researching Bruce’s story; providing so much more detail on what happened to Bruce and his service in France. I also acknowledge Peter's wife, Benita, who I'm sure has played a big part in its completion. Their story reinforces the picture we have of a young man doing extraordinary things. The book provides answers to many of the questions about Bruce’s activities in France and the circumstances of the underground group he was working for and the beterayal consequences not only for him, but other brave men and women whom he worked with. This book is not only about Bruce but of the many individuals who did their bit for the allied war effort. I also acknowledge Peter’s wife, Benita, who is also here, as I am sure she has played a big part in its completion. Several weeks ago, when I approached Laura Thomas about this book, she and others at the Shrine immediately saw the strength of the story and willing agreed to host this event. On behalf of Wesley, I thank them for being so receptive. In Bruce’s hometown of Melbourne, this is an appropriate place for Peter and Ken to launch their book on the Australian east coast.

Bruce would have been well aware of this building, maybe not this theatrette, but he would have been well aware of this building as it opened in late 1934, just as he was commencing his full-time teaching career a couple of kilometres down St Kilda Road. Its simply marvellous to see the interest in Bruce's story by those attending. I thank-you all for supporting this event. Now that’s enough from me. Thank you.

DEAN LEE: Thanks very much, Philip for providing some context to Bruce's story. Without further ado, I'd like to invite Peter to come forward to present the content of this evening's talk. And there will be opportunities for questions after the talk. So if you just think of anything, make a note and we'll cover that off with some microphones that will go around the room so you can all talk. Thank you

PETER DOWDING: Thank you very much, Dean. And thank you, Philip, for those remarks. Thank you to the Trustees of the Shrine for permitting this event to take place. And particularly thank you to Laura Thomas, who's been such a terrific help in putting it together. And I also acknowledge the people of the Bunurong nation whose traditional lands this is. I'd like also to acknowledge my cousin, Bruce Dowding, who's here. As you can understand the name ran through the family in memory and he's a little bit older than I am, not that much, but I welcome him here tonight. And my brother, Simon Bruce Dowding and his wife, Katie Lowe, and son Ruben. I need to acknowledge my indefatiguable wife, who who is here also thankfully hasn't run away after the pressure of putting these things together, and getting me on the plane and so forth. And also, I'd like to acknowledge my co-author, Ken Spillman, without whom this book would not have been written at least, legibly and enjoyably. There are some other dear friends here tonight. But I welcome all of you. And thank you very much for taking an interest in this story and, and in a story about a member of my family. But as Philip says, it's not just a memory of my family, it's a memory of, of the of the people with whom he worked. And in particular, of course, to remember the people who lost their lives in the overall activity, and there were many hundreds of them who fell. So what I would like to do tonight is, first of all, show you a short video that the ABC put together for Anzac Day, and allowed us to take a slice. And we took it and we put a French subtitle on it, because we're going to France, but it does tell you the story of the book in six minutes, so stand by, and I'll run that video.

For those wishing to watch the video, there's a link in the podcast description. But we'll pick up here after the video has ended.

I thought that was a marvellous piece from the ABC, and it actually tells you the story so we can all buy a book, go home and read it. Easy as that. Yeah, no, we don't need to do any more. I just thought instead of going through the history of the events so much, I'll just tell you a little about how the family saw it from here. My father lived in Melbourne and went to Scotland and then from Scotland, came back to Australia, lived in Melbourne and then Sydney and then went to Perth, and then went to India and then went to London and then went to Nigeria and then came back to Sydney and then to Perth all the time with a box of letters. The letters that Bruce had written to the family, the letters that the priest had written to the family, with the letters that other people had conveyed to the family, and a small pile of books that gradually grew over the years explaining something about the story of, of, of the events in France. So just let me take you to a couple of pictures. First of all, this is a just a small representation of the Dowding family as it was. In the bottom, you'll see the three boys, Bruce, the baby, Keith the middle, that's my father, and Mervin, that's Bruce's father, and above the same three of them. And on the right this, the same three with little little Bruce, who he was always referred to as little Bruce. And then below is Bruce on his way to France looking very dapper. And my father and Bruce in Sydney, where Bruce was about to catch the the boat.

And there is just an indication I think of the strength of the relationship with Wesley because it's actually an acknowledgement from Wesley that my uncle had been granted his football colours. And it's a remarkable thing I think that my father retained that that letter as evidence of Bruce's relationship with Wesley. And then this is a letter that the headmaster wrote to I suppose to validate what Bruce was doing, it was a sort of a reference to show that the school was agreeable to his going to France to learn some extra French and they actually gave him an advance of a salary to do that, on the basis that they hoped he would be back at the end of 1938. So he went ostensibly for this course at the Sorbonne, but I think secretly he really had any his head that he was going to a place of music and art and culture and cafes and all the rest of it that Melbourne did not have at the moment. We went to an exhibition today of some early Australian Art. And it was interesting to see how it blossomed suddenly with with the French influence. And I'm sure he was very keen to get there.

And there's a picture of him. The one on the on the right is him Bondi Beach about to head off looking very composed, and on the left in an orchard in Loches where in the Loire valley where he finally had a job as a live in housemaster. And on the side, he was allowed to teach wage, he wasn't allowed to work in France. But he, he, he scribbed and scrabed to make some money. Until, as we know, war broke out. And this is a map of France, when the Germans had invaded France. Just to put in perspective, what Bruce was up to and what happened. In the north of France, there were 1000s of servicemen who were overrun and 1000s, millions actually of civilians who took off when the Germans came in to the north of France, I think that was 6 million people went from the north to the south.

And if you read the book, you will actually read the story of a one, an Australian woman with a French name, and she tells the story of that exodus of people to the south. And in the north, the area called the Forbidden Zone. And it ran right around the coastal areas that people needed a special pass in order to move in and out. And that was a place of high level Gestapo activity to keep the resistance and the underground under control. Down south, it was a little bit easier in the Vichy France area during 1941. It got a bit tough. And by 1942, it was taken over taken back by the Germans. And you'll see that in the base, between Marsielle, around the corner, there are some small towns one is called Perpignan and in Perpignan, Bruce, for a while was the point man, as the liaison with the Spanish separatists. And so we have told that story in this book.

But one of the interesting things that you might find in the book is that we received or the family received this tiny photo in 1940 to show that Bruce was still alive. I'm sure you can't really make out the people in it. And so, in the last couple of years, we had the photo enlarged and clarified with some very high tech activity and that's the photograph as it emerged. Now why that is so interesting for us, is if any of you have seen a recent Netflix show called Transatlantic Crossing about Varian Fry and the American Rescue Committee, on the far side is Varian Fry. Next to Varian Fry is Bruce. Next to Bruce is Nancy Wake, and on this side of Nancy Wake is a man called Hirshman who was Varian Fry's offsider. Now if you read Varian Fry's reports of the war you don't read about Bruce, but it has always been my impression and I think it was Ken and my impression that it would be impossible for Bruce to be within a few kilometres of a bunch of intellectuals and artists like Chagall and others and not be involved. And as it turns out, he was the point man inPerpignan, at the Hotel Del Alize were all of Varian Fry's escapees went through and Bruce was the liaison with the Spanish separatists led by a guy called Ponzan Vidal.

Why that's so interesting is that a lot of the early literature talks about Ponzan Vidal and the Spanish separatists, the guides who were helping them over the Pyrenees, as smugglers. And as though they were criminal. Ponzan Vidal, in fact, was a lawyer, you might say QED. But, but he was a lawyer. He was in the group of Spanish separatists who had been defeated by Franco and they wanted money to raise arms to go back and attack Franco and So they were doing this for money, yes. But they were also on the side of the allies. And it's a very interesting photograph to link the Varian Fry story up with the story of my uncle.

One of the sort of misleading things that happened to the family after they had these messages saying Bruce was alive and well, Bruce was alive doing good work was that they received a telegram and the telegram actually didn't hit Melbourne until early 1942. And it's from a guy called Parkinson, who we know escaped at the end of 1941 with the pat line, the group that Bruce was working for, eventually made it to England, through Gibraltar, and sent this telegram. Now at this point in time, in fact, Bruce had been arrested. So when the family knew nothing about what had happened to Bruce, there were these quite misleading pieces of information that they did receive. And here's another one which came later in 1942. You'll see the 19th of July 1942, when Bruce wrote to his family this letter in which he said that he was fine and that he was he says 'Dearest mother and father Mervyn and Keith yet another effort to get some news of the prodigal through to you. Sufficient to ensure you have my absolute safety and perfect health, et cetera, et cetera. Of this last I trust you have never doubted as you may perhaps have had the reason to do given my own stupidity and egoism, but such as the way of all prodigals, and so is their eventual homecoming and forgiveness and of course, the fatted calf, my sincerest love to you all. And please do not worry too much about me, mother, and signed Bruce'.

Now what what what is misleading about this is that Bruce was never in that prisoner of war camp, the prisoner of war camp had been closed down at about that time. Letters from the family and gifts of cigarettes and so forth to the prisoner of war camp are all returned by the Red Cross, because Bruce had been taken by the Germans and made an NN prisoner that is a prisoner who's section was called Night and Fog. And the direction was that they would simply disappear into the night and fog and be a number, and never be seen or heard by any of the Red Cross or anything of the families or anything at all. So somehow or other, Bruce smuggled that out in 1942, with an optimistic letter, when we know at the time from people with whom he was imprisoned, and who survived, that he had absolutely no reason to be optimistic. So the family were in this constant state of not knowing what had happened to him having been given misleading information, and never being able to find any track through any of the established offices. So here's a picture which I can date at 1944. It's my grandmother and my grandfather. I've always looked at this picture and thought they look pretty unhappy holding this baby, that the baby was actually I'm told quite a nice baby because it's me. And, and, but but their sorrow is just it's this photo speaks of their sorrow, and particularly the sorrow of my grandmother. So then, when the war ended, there was information that came through the War Office, not terribly informative. In fact, it suggested that he had been presumed to have died after the first of March 1943 while evading the enemy from escaping from captivity. The family knew that he'd been a prisoner of war because in 1940, they'd received a letter from a prisoner of war camp. And then after the war, they received a letter from this guy who was a man called Vereslt, a Belgium, and he'd been in prison with Bruce.

And Bruce had told him about his escape from the prisoner of war camp, and how he had made his way to the south of France, and had been working with the underground and the Verelst in 1946 was asking whether the family could tell him did Bruce survive, and that he thought a great deal of Bruce. And then, in 1946, again, another letter came from a woman called De Segur, who wrote a piece for the newspaper. And she had quite a long article, in which she advised that Bruce had been one of her best friends, and that he had been taken away by the Gestapo and shot. So Wesley, and this is a wonderful part of Wesley's links with Bruce in the family, Wesley, put in these two articles in the in the newspaper, the first was dated May 1946. And the second I think, is December 1946. About Bruce for his work, and that was sourced from the De Segur article.

And then in early 1947, the family received a letter from the priest in Dortmund, Father Steinhoff, and he had taken it upon himself to secretly record the name of the people who were executed by the Gestapo, he taken a note of all their names, and their real names, not just their numbers, and their addresses as best he could and where their family were from. And he'd written to the family. And in order to find the family, he had written to some of the resistance groups in Paris that he knew of, and he'd asked them, if they could possibly put him in touch with the family. And he had obviously had no more than a few minutes with Bruce, at the time of his execution, but had noted this information down about him, and noted that he wanted to be baptised a Catholic as he was about to die.

Very interesting, the last sentence, I think, or the second last sentence, is that that he obviously had adjusted mentally to the fact that he was going to be executed. And he was executed with the people with whom he'd worked in the, in the resistance movement. One of the things that we have tried to do in this story in the book, as you will find, is we don't want to airbrush out the people that Bruce was working with and pretend that he was on his own. I saw a presentation that had been made in France, about one of the people that Bruce had been executed with, and they listed the French people and their execution from seven o'clock, 7:05. 7:10, 7:15, 7:20. And then they left out at 7:25, Bruce Dowding, and I've felt that that was an example of what we were really keen to avoid. Over the years, the search for Bruce has become something I suppose you could say of an obsession of my father and an obsession of mine, that Bruce was a sort of elephant in the room, the story throughout my life, and uncovering what had happened and exactly who he'd been involved with and how he had been involved was a very long, slow process.

It wasn't until about eight years ago that that MI9 and MI5 and MI6 and the security services started to release their hold on documents and so forth. So my father travelled to meet with people to search when he was in Europe, and I'd done the same. This was at Bruce's grave until the war graves had finished their their work in Kleve in Germany, and that's my father in the 1990s at the final grave that exists at the present time. And there's a photo of me at the same grave in Kleve in 2013.

Now, you, you might ask why we wrote this book. And first of all, I should say, we wrote the book. I'm very grateful for my co author, Ken Spillman, who's here. One of my friends who I had shown the manuscript I'd written by myself. Other than expletives about the book, and said 'This is absolutely shit'. And he, he said, 'Look, you're writing it like a lawyer, addressing a judge who is paid to stay awake'. So he suggested that really, there were other things that I could do. And one of them was to get someone to help me craft it into a book that someone might find readable. And Ken and I really hit it off during 2001, we worked, because we couldn't travel because of COVID, and so forth. So we worked on it all year, really intensely, I must say we had a huge amount of research to go through, someone asked someone here who knows me, as a lawyer said, I bet you had a chronology. And I said, I did have a chronology, it's 2000 pages long. So so it was a huge amount of research and a tremendous amount of work to put it together. And I'm very grateful to Ken because I think you will find it much more readable than the original manuscript. So why is this picture up on the on the screen? And the answer to that is, because it's sort of the reason to write the book. And for those of you who know it, it's a picture of Icarus, who flew too close to the sun and his wings, the wax on his wings melted, and he fell into the ocean and W H Auden wrote a fabulous poem called THE Musée des Beaux Arts. And the last sentence of it is in In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on. So this is a story to try to try and draw your attention to Bruce Dowding who, like Icarus, fell from the sky and is worthy of a story. Thank you.

DEAN LEE: A terrific presentation. And I think really, we can see the passion and the spirit that Peter has brought to telling the story of his uncle with the assistance of Ken. And I think we're very fortunate to have both of them here in the room with us this evening. If there are any questions, I believe both of you are happy to answer any questions. Yeah, absolutely. Just raise your hand and Laura will bring a microphone to you. You may think you have a loud voice. But in this space, it won't carry that far without the microphone. I have one for you, Peter. I think the thing I found fascinating in all of this is the is the human story. And this place that we're in at the moment is all about human stories of service and humans stories of sacrifice. We don't celebrate the militaria or we don't celebrate the politicians all due deference to yourself.

PETER DOWDING: It's outrageous`

DEAN LEE: It is outrageous, but it's a contestable view. I think, when you were drawn to discover this story, did you feel any form of duty to your family? Was that part of what drove you to do this?

PETER DOWDING: Yeah, I guess, I guess, look, I knew how much my father felt about this. It's interesting, because I was talking to my cousin Bruce, who was who was with Merv and in his household, and they didn't talk about these things very much. In my household, it was a constant reference to Bruce. And I felt originally that I wanted to bring some closure to my father, of course by trying to find this story, but as it turned out, it took a lot longer than I had expected. And then for the reasons I think, having met so many of the people and so many of the relatives of the people who were involved and the hardship that they underwent and the bravery that they all showed, I did feel an obligation that we should put this on the on the public table.

DEAN LEE: I felt, I thought that might be the case because there's obligation I think we certainly here at the Shrine feel that obligation to tell truth to these stories, do we have a question?

AUDIENCE: I'd like to know was there a point in the story where you got very emotional or, you know, it's it's such a great story that even I feel emotion.

PETER DOWDING: Look, the emotion still does grab me as, as my wife knows, I had to practice that W H Auden poem a couple of times today, because that really does grab me as a as a story. It actually references executions. I didn't deal with that bit of the poem. But look, it is an emotional story. And we've had some wonderful experiences. They group World War Two Escapees Memorial Society in England, who who remember helping the help from the French and the English and the Australians and so forth. They've been fabulous. And they actually held a little memorial service in Marseille for Bruce, which was a very emotional moment. And then my wife and I are going to Belgium, we're going to Dortmund where Bruce was executed, and then Belgium in October, and we're meeting we're having an event in Belgium with Patrick juries, who is the son of the organiser of the organisation who gave his name Pat to the body. So we've still got a bit of emotion to run yet, I can assure you, thank you for the question.

AUDIENCE: Were there sleepless nights where you were thinking, I can't let this go?

PETER DOWDING: Well, gathering this information has actually been a real job as Ken knows, we've had we've had, we really have dealt, dug, dived deeply into information sources to try and understand what was happening. Because MI9 material was so misleading early on. The sleepless nights have really come from the sort of anxiety of wanting to tell the story truly and correctly and having to dig to find what happened. Whether Ken wants to comment on that.

KEN SPILLMAN: I can certainly say that I was emotionally affected by the material that had been uncovered in the course of preparing this book. I'm told by somebody very close to me that I was tossing and turning at night a great deal during the period, when I was so immersed in this story, I was working with Bruce's photograph, clearly visible just above my computer monitor. And from time to time when I was pondering the material, I would just look up at him and eyeball him if you like. And there were certainly times when I felt emotional in the work. But I know that it was occupying my mind at some level all the time when I wasn't working as well. Because you know, it was something that really we felt together that we needed to do justice to those people who had who had really given so much. And one of the things that really affected me, initially when Peter was telling me the story when we were first talking about this was the story of a guy called Dupray who had two Legion of Honour medals in his possession, one which had belonged to his father, who was a member of the organisation that Bruce was a member of, and one which he had earned himself. And because Bruce Dowding had been nominated for a Legion of Honour by the French government and that the Australian government has failed to act on that, he presented Peter, he presented the Dowding family in fact, with with one of those metals, one of those Legion of Honour medals, and I know that's a very emotional thing for the Dowding family. But certainly when Peter was telling me that story, I was moved to tears.

AUDIENCE: I'm just wondering what it was life for you as a child watching Dad pack this box of letters to every country. What was what was that impression for you?

PETER DOWDING: Well, I think I've said earlier it was like the elephant in the room. Our lives went on. We had lots of other dramas in our lives, but it was a constant that that my father had been, and the family had been deeply affected by the loss of Bruce and, and he, he wanted to maintain Bruce's identity. And in the book we have used the letters quite extensively because Bruce wrote every week, from the moment he left Melbourne, to the moment, he joined the army in France almost every week without fail, and we know something about his life and the people he mixed with about his love affair, about his experience in Paris. It's a very interesting journey. And of course, I suppose you might think we were obsessed, we weren't, I mean, life went on. But it was one of those things that you had in the family. And you knew about

AUDIENCE: I'm from Wesley Collegs so I've been following the story closely through the communications that we're working on. What I'm most interested in is, why do you think the Australian Government had that reaction at the time when the medal was offered? And why has there been a reaction now since your story, has that changed? What have they said? Do you know why?

PETER DOWDING: Well, what happened originally was that MI9 and the resistance formed a committee in Paris, immediately the war ended, to identify the people who should be awarded for their bravery. And that was, immediately the war ended. And Donald Darling, who was the unlikely named head of the MI9 operation in Gibraltar, during the war, went to Paris and one of his tasks was to form that committee. And eventually, the French government wrote to the Australian Government and said, 'We would like to bestow this honour on they called him Captain Dowding.' And the Prime Minister's department asked the three services 'Do you know, a Captain Dowding who was actually lost during the war?' And they all wrote back and said, 'No, he wasn't one of ours'. Someone in the prime minister's office said, 'I think they're talking about Bruce Dowding, and his family lives at...' and gave the address in Glen Huntly. And the Prime Minister's department just wrote back to the French government saying, essentially, he wasn't one of our people that was killed, and it's not appropriate for an award to be granted in those circumstances. Now, since then, in the last 15 years, we've made a few approaches to the French Government without much luck. We're still trying to wake the current government up a bit about it. Without much luck. Someone here, mentioned, as they were coming in, that they had some experience of people who are alive, who were granted a Legion of Honour many, many years after the war, but the government in France had a policy of not doing it for posthumous awards. But we're going to Paris, we got the ambassador on side, we'll let you know, work in progress.

AUDIENCE: Thank you, Peter and Ken for your work and amazing work. I've just got a question about what it must have been like to read what you had all the letters, but then you needed more to, to put all this together? What it was like actually seeing some of the MI9 documents and the other documents you saw was what was that like reading those?

PETER DOWDING: Well, we were we were really, we were really fortunate in the sense that I went to both the British Imperial War Museum who were no help at all about 10 years ago, and then I went to the British National Archives. And that was really hard yakka because they weren't releasing things, you had to ask for things. And if you didn't know, you couldn't ask, I mean, obviously, and then when COVID hit the National Archives in Britain released a lot of their material which had been digitised online for free. And not that the cost of inhibited us, but was just not knowing and being able to search for it. So getting those MI9 records was really important, including a very extensive I9 report on Cole. I mean, I don't know 50 pages probably of it, dense, dense materials. So that was enormously helpful and and equally very, really very emotional stuff. I mean, I think Ken would agree that at times we had a really emotional ride putting this story together. And that was one of the reasons. We were uncovering stuff that people hadn't written about before.

AUDIENCE: I was fascinated by how he became a Catholic shortly, virtually on his deathbed, did the priest elaborate on that more, or was it common or any reason?

PETER DOWDING: Well, he was he was actually he became very friendly with a priest called Carpentier here in the north of France when he went north. And Carpentier was a very charismatic man and a very charismatic priest. And we have some stories from people who were in prison with Carpentier at the same time, as Bruce was there, we know they were all together, some of them don't mention Bruce. But they certainly mentioned Carpentier who would sing hymns at night in the in the prison loudly, he would, he would, you know, give people the benefit of spiritual support during the two years that they were essentially in or the 18 months they were essentially in prison. And I'm sure that that's what impacted on Bruce and his and his final decision. And he was also Bruce was also, he was quite a spiritual bloke, as you will see from the book and the stories that he wrote.

KEN SPILLMAN: I can just add something to that as well. In in Bruce's letters to Keith, Peters father, who quite often discussed matters of religion. And he was quite entranced by the relative flamboyance of French Catholicism. From the time he got there, he referred to dry Presbyterianism, and this was a little bit provocative, of course, because I don't know if you know, but Peter's father was a Presbyterian minister. And at the time, he was training to become one when when Bruce was writing to him, but he certainly did like the kind of iconography and he liked the myths, what he called the mysticism of the Catholicism of the time. And so he was he also saw himself as a little bit of a rebel. And so he didn't mind embracing that. I think.

AUDIENCE: I just wanted to know what happened to his Swedish sweetheart.

PETER DOWDING: Well, well, she as Ken tracked down amazingly really that she actually was the half sister of Bruce's best friend in Paris, who was a Swedish artist. And she was from a Jewish family, or had a Jewish ancestor. And when the Kristallnacht event took place, she decided, I think that she would be safer in Sweden, and she went back to Sweden, hoping that Bruce would follow but he didn't.

AUDIENCE: And is there any link between that part of the family?

PETER DOWDING: No, but I met Max Builder, her her brother, who Bruce was very friendly with. And you'll see that in the book, there is a picture that Max had given me of Eva Greta, which we've had enhanced to try and make it clearer, and she is a very beautiful woman. But when I went to Sweden, she was very elderly in an old people's home, and I wasn't able to meet her, but nothing happened further in their relationship after she went back.

DEAN LEE: We have time for one further question.

AUDIENCE: Peter, Bruce was obviously liaising also with the Spanish, presumably to get escapees over the Pyrenees to Spain. Were there any sources from Spain that related to the work?

PETER DOWDING: Yeah, in fact, this is part of the book but for the aficionados of the MI9 story, you won't find any reference to Ponzan Vidal much and what they were doing. We have looked through some French material and some Spanish material. And in the book, we elaborate on that. Ponzan Vidal was very active, and his group was very active, and they continued to be active after he was arrested. He was put in a prison in the south of France. And as the Germans were retreating, they took 40 of the prisoners out, including Ponzan Vidal and shot them. So I think you'll find in the book, a story that Ken and I both feel has not been told, and that is the the life and times of the Spanish separatists. And we found that Bruce, in fact, had remarked in 1939, that he had not only spoke impeccable French, but that he had also learned Spanish. So he was the points man in, liaison with the Spanish separatists

DEAN LEE: Thank you very much, Peter.

PETER DOWDING: Well thank you all very much indeed.

Updated