- Service:

- Air Force

The Shrine Stories podcast takes you on a deep dive behind the objects on our gallery floor.

In this episode, we delve into the story of Flight Sergeant Keith Meggs. Keith had a passion for aviation from an early age and in December 1950, he arrived in Korea to serve as a fighter pilot. Over the course of his service, he was involved in two very close calls.

Listen as Shrine Curator Neil Sharkey uncovers these stories and the peculiar way Keith got his hands on an American survival vest.

Music: Across the Line - Lone Canyon

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance embraces the diversity of our community and acknowledges the Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which this podcast was recorded. We pay our respects to Elders, past and present.

NEIL SHARKEY: if he had been wounded in any way, it's probably doubtful that he would have had the presence of mind to be able to crash land the plane or even bail out of it, you know, or even, you know, he may have been killed outright as his plane was struck by ground fire. So, very lucky, very lucky.

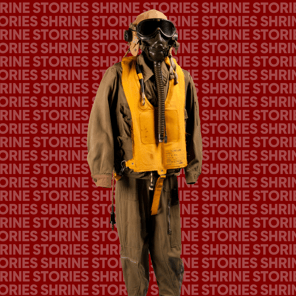

Welcome to the Shrine Stories podcast, a place where we take you on a deep dive into the stories behind the objects on our gallery floor. My name is Laura Thomas, and in this episode of the podcast, we’re going to be exploring the story behind a flying suit that’s house in the Korean War section of the galleries. Now this suit belonged to Keith Meggs, who joined the Royal Australian Air Force in 1948 and arrived in Korea two years later. During his service in Korea, Keith made not one, but two lucky very escapes, which we’ll get to soon, but first, I’d like to introduce you to our guest today, Shrine curator Neil Sharkey. Neil has been at the Shrine since 2007 and in that time, has developed the Shrine’s Second World War Gallery and dozens of special exhibitions. Welcome Neil.

NEIL SHARKEY: Thank you, Laura.

LAURA THOMAS: Now before we jump straight into his service in Korea, can you give me a little bit of background about who Keith Meggs was?

NEIL SHARKEY: Certainly, Keith Meggs was born in 1928 and became obsessed with flying as a boy in 1934 when he saw the winning aircraft of the Centenary Air Race, which was a Scott and Black DeHavilland Comet fly over his childhood home in Northcote. He joined the Air Training Corps during the Second World War, which was a like a cadet organisation that was established for young boys, which allowed them to get Air Force training before they were actually of legal age to join the RAAF. So it was a way to get them up to speed, and he joined that while he was still a student at Northcote High. And he continued to serve in the Flying Corps when he began working at the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation factory at Fisherman's Bend.

LAURA THOMAS: So he was involved in building aircraft.

NEIL SHARKEY: Yes, that's right. It was like everything in Keith's life was built around aircraft. So Keith's original ambition had been to join the RAAF, during the war. And he would have done so, but the war finished, you know, earlier than it was expected. When he was only 17. And pilots just weren't required any more. There was just more pilots than the RAAF knew what to do with. So in 1948, he tried to join the Royal Australian Navy's Fleet Air Arm. So that service did require pilots at that time, because Australia had just bought two aircraft carriers and so they needed pilots for that. But unfortunately, he was deemed too short by their service, so he couldn't join...

LAURA THOMAS: Heartbreaking.

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, and when we see his flying suit on display here at the Shrine, we can see that he certainly wasn't a tall guy. But luckily for him later in the year in 1948, the RAAF were starting to recruit pilots again. And he managed to get in so yeah, and after training was posted to No.3 Squadron in Canberra. And immediately, the outbreak of the Korean War, four the more experienced pilots in the in number three squadron was sent to Japan to join number 77 Squadron there. But he had to undertake additional training before he was sort of ready to join them. And he did. So he and some of the younger pilots were then flown up to Japan in December 1950. And from there, he went to Korea and was in Korea on the 22nd of December 1950.

LAURA THOMAS: What were those early experiences like for pilots like Keith in Korea?

NEIL SHARKEY: Oh, yeah, look, Korea was, it was pretty hectic time. So immediately, just for a bit of context, immediately prior the outbreak of the Korean War, the air and ground crews of number 77 squadron had been actually preparing to leave Japan forever. The squadron was based at it Iwakuni Airbase, and had been a key component of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force, and had been there since March 1946. So the Squadron were actually enjoying farewell celebrations when news arrived that North Korea had invaded South Korea. And so the decision for the squadron to return to Australia at that time was immediately rescinded and they were placed on standby for action. What had happened was that General Douglas MacArthur was the commander of the United Nations Forces in the region. He was just dragging together whatever forces he could find in Japan to send to South Korea to aid them and he specifically requested the participation of number 77 Squadron because it was equipped with Mustangs, which even at the dawn of the jet age, they were still the best long range ground attack aircraft in theatre. And the Australian squadron number 77 was considered the best Mustang outfit in Japan. So that was super valuable. And MacArthur wanted them in action straightaway. And indeed, they were the first Australian units involved in the Korean War. So, yeah, I mean, you can just imagine, you know, just going from one set of expectations that, you know, You're going to be heading back to Australia to like being in the middle of war zone, and in the middle of a war is quite a turnaround. And the aircraft they had, the Mustang, I mean, it was obsolete by that time, but it was still very well equipped for fighting ground attack missions.

LAURA THOMAS: So that was the kind of thing that they were doing?

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, yeah. Because what was happening is huge numbers of North Korean soldiers, who were very well equipped by the Soviet Union, they had, you know, t 34. tanks and trucks and all the rest, were streaming down the Korean peninsula, and the South Koreans didn't really have anything to stop them. And the American and United Nations forces were not yet in force in order to help the South Koreans. And so what the Mustangs were tasked with doing was just destroying as much North Korean equipment as they could. So all of these tanks and trucks and trains coming down the peninsula, supplying the North Korean forces at the frontlines. The Mustangs, it was their job just to destroy as much of that as possible just to slow them down and just to buy time. That was before Keith arrived, but you can just imagine that is what he arrived at. Like that was the sort of situation that was going on when he first started flying combat missions out of Busan.

LAURA THOMAS: And it changed over time once he arrived?

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, sort of about the time that he arrived, the United Nation Forces were beginning to get the upper hand and push the North Koreans back. There was a massive American invasion and landing at a place called Incheon, which was behind the North Korean lines. Close to Seoul, in fact, because by this time, the, the North Koreans had almost reached right down to the southern tip of Korea. So when the Americans landed at Incheon, that threw the North Koreans into disarray, they began withdrawing as quickly as they could, and the United Nations forces were successfully pushing them further north. And number 77 Squadron, were part of that, as was Third Battalion, Royal Australian regiment soldiers that were part of that move north. And that continued whereby the United Nation forces were able to push the North Koreans all the way back to the border with China in October, and that's when the Chinese joined the war. So that was, yeah, I mean, so the Chinese had rejoined the war when, when Keith was involved, but you know, that changed the whole dynamic of the conflict. So once the Chinese were involved, then it was, it became a much more evenly matched affair. And so it started off a whole, a whole other catastrophe for the United Nations forces.

LAURA THOMAS: How did the United Nation forces then respond to that?

NEIL SHARKEY: With the Chinese, when they came, they brought with them hundreds of new cutting edge swept wings Soviet built MiG-15s. So this is like the best fighter aircraft in the combat at this stage, bar one possible exception, which was an American built aircraft, very similar in appearance called the Sabre. And the Sabre was really the only plane that could bring it up with the MiGs. And so it was at this point that the shortcomings of the Mustang, which was a propeller driven plane, first became apparent when it was up, or threatened with these MiGs. And so the Australian Government was very keen to update the aircraft and the aircraft they wanted to, of course, was the Sabre, but the Sabres were not available because the American Air Force was taking every single Sabre that was coming off the production line, Because they, you know, in order to match it with the mix, and so, the only aircraft that was really available to the RAAF at this time was a British built jet called the Meteor or the Gloucester Meteor. And this was an aircraft that was actually from the Second World War itself. So this very early generation jet plane, it was by no means cutting edge, but it was just the only, it was the only plane available. And like the Mustang, before it was really kept in that ground attack roll. It was still not up to dogfighting with the MiGs. So yeah, look, I mean, the sort of work that the pilots were doing in in Korea was was very dangerous, just sort of standard missions, I guess that they would fly is that small groups usually two or four Meteors would take off. They would receive a briefing about where possible Chinese or North Korean targets were. And then they would just fly out looking for those targets and engaging them. And for the most part, the greatest threat to the pilots was ground fire rather than MiGs, because what happened was the American pilots flying the Sabres would engage the MiGs further north, and just try and keep them out of the battlespace and so that the aircraft, like slower aircraft, like the Meteors could concentrate on destroying ground targets.

LAURA THOMAS: So as you mentioned, it was inherently dangerous work. And I've alluded to the fact that Keith himself had a couple of close calls, hairy experiences in Korea. Can you explain them for us?

NEIL SHARKEY: Yes, so in March '51, a couple of weeks before the pilots left Korea to go to Japan for this conversion from the Mustangs to the Meteors, so you know, he was still flying a Mustang at this point. He was shot down so he was forced to emergency crash land at an old aerodrome at Kimpo near Seoul. So by This time of the war, that's very close to the frontlines. A few days later, there was, I guess, another dramatic incident, a rescue. So a friend of Keith's, a fellow pilot, Cec Sly, was shot down, and he was forced to bail out behind enemy lines. So What Keith and another of their friends had to do, another pilot, had to circle Sly while he was on the ground, and strafing the enemy troops that were closing in on him, and trying to capture or kill him. So the guys had to call in support, call in for support, you know, other American and Australian pilots then had to come in and you know, join this picket of just circling Sly until they managed to get a helicopter out to rescue him. Now, they had to send two helicopters. In fact, the first helicopter was shot at and badly damaged, and it had to withdraw. And then they finally got a second helicopter in there that got him out. So yeah, just amazing.

LAURA THOMAS: How lucky was Keith and Cecil, I guess, in this situation to have survived both of these incidents?

NEIL SHARKEY: I think they were about as lucky as my description of the action makes them sound. So that same ground fire that brought down Sly was still being held up at the aircraft circling above them. And, you know, could have just as easily taken them down. And I guess the American helicopter, first American helicopter is a case in point of that. And we can also see from the previous episode, you know, a few weeks before when Meggs was himself shot down, if he had been wounded in any way, you know, by bullets or cannon shell or shrapnel, it's probably doubtful that he would have had the presence of mind to be able to crash land the plane or even bail out of it, you know, or even, you know, he may have been killed out right as his plane was struck by ground fire. So, very lucky, very lucky.

LAURA THOMAS: And am I right in saying the first incident, he actually didn't know whether he'd landed on enemy territory or not?

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, yeah. Because that section of the battlespace where he was was right on the frontier between the two opposing forces. So the front line at this point was just a little bit north of Seoul.

LAURA THOMAS: We mentioned that we have Keith's flying suit on display. You said it's not very tall. He wasn't a very tall man. But what are some other features of this suit?

NEIL SHARKEY: Oh, yeah, it's, it's a great thing for the Shrine to have on display. For any visitors looking at it, they will see a real evolution from you know, earlier flying suits that we have on display from the First and Second World War. It's a lot more modern looking than some of those others. It consists of a jumpsuit like sort of overall jumpsuit with a what's called an escape and evasion vest. And with like a life preserver over the top of that. The survival vest is is really interesting. It's actually American in design and, and you can see that when, when the life preserver is off, there's an American Airforce markings on the vest. And the reason for that is, at this time, the equipment that was used by American service personnel was just far superior to kind of the the stuff that Australians were wearing, or went into the combat wearing. It was just a lot more modern, just more ergonomic, just better designed and built. The vest itself is just really tremendous thing, it's like a fishing jacket. It's got lots of little pockets. And in each of the pockets are just little useful things that would help you in the event that you're shot down behind enemy lines. So there's like a survival guide book. There's a mosquito net you know if you have to make a little Hutch for the night and you know you need to be protected from insects. There's emergency signal mirror, bottles of Halazone, which is like a water purification tablet. Yeah, just it just has these things ready to go. So because in the Korean War, if you came down behind enemy lines, and there was no one to help you, you're in a lot of trouble because the North Koreans and the Chinese did not treat United Nations pilots with kid gloves, I'll tell you that. At this stage of the war, when the frontlines were very fixed, a very large percentage of the United Nations prisoners that were taken were airmen, because they were the only ones that were routinely crossing deep into enemy territory. I mean, I'm not saying that soldiers weren't captured by the enemy, but they were usually not as far behind their own lines. It was easier for them to get back generally speaking than it was for a pilot who was shot down.

LAURA THOMAS: So it was important for Keith to have these kinds of things on him. But how did he get his hands on it? Was it common that Australians would be purchasing things?

NEIL SHARKEY: Well, the story was that he made a trade with an American for a bottle of whiskey. And that's how he managed to get hold of this stuff. And that was really quite common at the time, because this American stuff was so much better than was typically, you know, or originally issued to the Australians anyway, the men often would, would trade and so forth until they got this stuff. And until the RAAF realised, oh, look, the stuff that we've given our guys is not really good enough, and then started being able to get it on mass from the Americans. And look, it usually wasn't an issue for the Americans anyway, they just had so much stuff, so it was just, you know, like, for them a bottle of whiskey was worth a lot more than something that they could just lift from the store.

LAURA THOMAS: More than a fair trade.

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, I guess that's, that's what a good trade is, isn't it? You give up something that's not very valuable in the hope that we get something that's more valuable, I guess.

LAURA THOMAS: And we know that Keith stayed in Korea until 1954. But what did he go on to do after his service in Korea?

NEIL SHARKEY: Well, as I mentioned before, Keith remained obsessed with aircraft for his entire life. He joined the Department of Civil Aviation as an air traffic controller before taking up freelance charter flying. And he did that for like 25 years. And by the end of his career, he had flown something like, almost 20,000 hours on 109 different aircraft. So you know, he was, it was really, whenever he had an opportunity to fly an aircraft he hadn't flown before he just jumped at it. He just really lived for it. He was a foundation member of the Aviation Historical Society of Australia, which was formed in 1959. And he was president of that organisation from 1988 to 2013. Over five decades, he compiled a full volume comprehensive history of 100 years of Australian aircraft building. So yeah, he just really right up until the time he died, which was not that long ago, he was just absolutely at the pulse of aircraft history in this country.

LAURA THOMAS: Lived and breathed it.

NEIL SHARKEY: Absolutely.

LAURA THOMAS: So why should people come into the Shrine and see Keith's flying suit?

NEIL SHARKEY: I mean, these Korean War era flying suits are not that common. For starters, there was only one ever Australian squadron that was involved in the conflict. So, A. But B, Keith was just such a, you know, I had the pleasure of meeting many times, he was just such a great character. He just lived and breathed aircraft. He loved the RAAF. He did everything he could to promote the memory of those pilots in Korea, and for the aircraft that they flew. And I think that the fact that he donated this flying suit to the Shrine, I think is just a tremendous privilege for the Shrine. And it's just wonderful to be able to share it with the people of Victoria.

LAURA THOMAS: Thank you so much, Neil, for sharing Keith's story.

NEIL SHARKEY: My pleasure. Thank you, Laura.

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks for listening to This episode of the Shrine Stories podcast. For more, search Shrine Stories on your preferred podcast platform. Otherwise, we'll see you next time.

Updated