The Shrine Stories podcast takes you on a deep dive behind the objects on our gallery floor.

In this episode, we explore the story behind a Norwegian language certificate that sheds light on the lengths some prisoners of war went to to escape captivity during the Second World War.

The certificate belonged to Squadron Leader James Catanach, and for fans of the movie ‘The Great Escape’, this episode is sure to interest you.

Music

Across the Line - Lone Canyon

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance embraces the diversity of our community and acknowledges the Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which this podcast was recorded. We pay our respects to Elders, past and present.

Welcome to the Shrine Stories podcast, a place where we take you on a deep dive into the stories behind the objects on our gallery floor.

My name is Laura Thomas and I’m the production coordinator here at the Shrine.

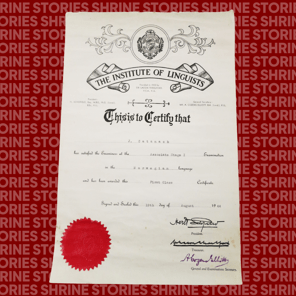

In this episode, we’re exploring the story behind a Norwegian language certificate that sheds light on the lengths some prisoners of war went to to escape captivity during the Second World War.

The certificate belonged to Squadron Leader James Catanach, and dates back to August 1944, and for fans of the movie ‘The Great Escape’, this episode is sure to interest you.

Joining me now to uncover this story and shed light on the certificate and its links to The Great Escape is Shrine Curator Neil Sharkey…

NEIL SHARKEY: Hello, Laura. How are you?

LAURA THOMAS: I'm good, I'm good. Now, I was hoping we could start by you telling me a little bit about James's military life. When did he enlist and what was his early career like?

NEIL SHARKEY: Okay, James enlisted in the RAAF on the 18th of August 1940. He trained in Australia and Canada, before he was posted to number 455 Squadron RAAF and they were stationed in Britain. He, he quickly proved himself an accomplished pilot, he was a natural leader. He flew strategic bombing raids with Bomber Command, which is the command that number 455 was originally part of, from April 1942, though the squadron was transferred to coastal command because the aircraft they flew, which was a Hampton bomber, was much better suited for that type of operation, rather than strategic bombing. Now on 26th of June 1942, James became the first Australian in number 455 squadron to receive the Distinguished Flying Cross. So you know, it's a it's a valour decoration and very prestigious one. The Shrine collection that we have about James has a newspaper clipping from the collection from The Sun, for seventh of October 1942. So yeah, like he was he was a big character, he was very sort of likeable chap, by all accounts. When that that article from the Sun was published, though, Jimmy had already become an inmate at Stalg Luft III. Now what had happened was, James had been, along with the rest of 455, had been sent on a special mission to Russia to a place called Venga in the Soviet Union. Now, what was happening there was that there were a lot of convoys bound from Britain to the Soviet Union to provide them with arms. And the convoys were being menaced by U boats as they crossed over the Norwegian coastline. And so it was thought that if the Hampton torpedo bombers that the 455 had, if they could be transferred to the Russians, and the Russians would have some way to counter these U boats. And so all of the squadron was flown, you know, flew to the Soviet Union to deliver the planes. But unfortunately, some of the planes were shot down on route and James's plane was one of them. So that was the fourth or the fifth of September 1942 that that happened. So they came down in Finland, which was near the Finnish Norwegian border, one of which was occupied territory. One was fighting alongside the Germans against the Russians. And yeah, and so that's how we ended up in German captivity.

LAURA THOMAS: What was his life like when he was in captivity? Can you describe the conditions of the camp that he was in?

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, look, Stalag III was a purpose built Luftwaffe for run prisoner of war camp for captured allied airmen, offices primarily. It lay in a clearing in a pine forest in the German province of lower Silesia near the town of Zagan. Today that that town is, is in Poland, actually, there was a border redrawn. The site was selected because it was deep inside the reich and the local sandy soil there made tunnelling difficult. So that was part of the reason they set up the camp there. The camp comprised five compounds that covered about 24 hectares, and it housed 11,000 inmates so a lot of guys. Guarding these prisoners was 800 Luftwaffe personnel, and they were mostly guys who were too old for combat or young men that had been injured and were, you know, convalescing. Each compound consisted of 15 single storey huts raised from the ground on stilts. So that's what the camp basically looks like. Stalag Luft III was, by Nazi standards, a pretty well administered camp and the Luftwaffe accorded far better treatment to their charges than any of the other German services, certainly better than the army or the SS. Every compound had athletic fields and volleyball courts. There was even a six by seven metre pool that was used to store water for firefighting and the Germans let the prisoners swim in it from time to time. The prisoners had access to a library and correspondence courses. And these were supplied by the Red Cross so the men could study engineering, law, literaturem languages. The prisoners in North compound where Jimmy were built a theatre and put on biweekly performances of current West End shows. Camp intercom was used to broadcast news even and, and music. There was two newspapers, The Circuit and The Kriegie Times were published four times a week. So in short, the prisoners had everything they needed to see the war and peace. So, you know, it was definitely one of the better camps that were the James could have ended up in.

LAURA THOMAS: So despite this quite comfortable life that they were living, and ironically, with the camp being designed so that prisoners couldn't escape, a plan was hatched for them to escape. Neil, can you tell me a little bit about how it came to be?

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, the Germans did their best to design a camp that couldn't be escaped from but you know, the thing with, when you lock up a lot of very intelligent, you know, well motivated, guys with a lot of skill sets, you know, you can never, you can never say they're never going to escape, or they're never going to try to escape. So yeah, look, I mean, the the enemy did their best to mollify the prisoners. But in the spring of 1943, an escape committee had been formed. And the key chap in charge of that was a guy called Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, who was a South African born guy who had been serving in the RAF before he was shot down. He was codenamed Big X. And he conceived a plan for a mass escape from the camp. And look, yeah, I mean, Bushell was just a really sort of driven guy, and he appealed to his comrades patriotism, you know, and he found a pretty receptive audience on the whole. To survive psychologically, as a prisoner of war, you know, life needed purpose. And, as I said, idle in the camp were some of the keenest minds and most courageous characters in the in the RAF and the RAAF and other air forces. So, you know, I mean, the honour demanded, you know, that they try their best to escape and, you know, many felt duty bound to try. So, Bushell's plan called for the construction of three tunnels, and they were codenamed Tom, Dick, and Harry. Now, as I mentioned earlier, all of the barracks that the prisoners lived in, were built up on stilts, and this was so that the Germans could see if anyone was trying to dig tunnels. So the only place where tunnels could be dug were, you know, areas of the buildings and camp that made contact with the ground. And so this was things like, for example, I mean, Tom's entrance began in a darkened corner next to a stove chimney in Hut 123 and Dick's entrance was hidden in the drain sump of the washroom in Hut 122. Harry was hidden under a stove in Hut 104 So, you know, this is the sort of ingenuity that the prisoners used. Bushell believed that the existence of three tunnels guaranteed that at least one would succeed. The tunnels were deep, you know, they had to go down deep about nine metres below the surface. Because, I mean, the Germans had implanted microphones and things in the ground, you know, to, to listen out for these, you know, for digging and that sort of thing. The tunnels, I mean, they just weren't tunnels, they included workshops, they were air pumps, and every few metres there would be like a, like an area would be excavated out and then little staging posts. So you know, you could string men along the tunnel and, you know, store them at areas along its length because the tunnels were very long.

LAURA THOMAS: And where were they getting the kind of equipment and things to actually build and construct these very complex tunnels, you know, nine metres deep. You can't just be doing that all by hand, can you?

NEIL SHARKEY: They definitely had tools. These guys just became really expert at, you know, they would steal, they would steal tools, they would make things, you know, using scraps of metal they would, you know, form up the, the spades and the picks that they needed. But you know, I mean, the digging tools that was just one component of these tunnels, I mean they, they stole wire, you know and bulbs to provide light inside the tunnel, they made ventilation pipes using cans of condensed milk, you know, once the milk was gone, they'd knock out the bottom of the cannon and they just sort of slot one can into the other. And just, you know, that would provide the piping. They were very, very resourceful. They forged papers with the art supplies that the Germans had given them, you know, for drawing classes. Anything that they couldn't steal, they would bribe or blackmail guards to get them. Yeah, just as I said, there was a lot of very intelligent, resourceful men with a whole range of skill sets from civilian life that were able to, you know, be put to useful purpose. So even the guys that didn't escape from the camp, were probably involved in doing something to aid in this escape. So, you know, if you're a graphic designer, you'd probably be put to work forging papers, you know, if you're, if you're a miner, you'd probably be working in the tunnel. You know, that sort of thing.

LAURA THOMAS: Yeah, everyone played to their strengths.

NEIL SHARKEY: Now on the night of the 24th of March 1944. Harry, so one of the tunnels that they dug over many months, was found to be short, you know, when the men emerged from the, from the tunnel, they realised that the tunnel was short, five metres short, in fact, of a tree line that was supposed to conceal its exit, you know, so it's just sort of popped up in the middle of an area instead of behind the trees where where it wouldn't have been seen, of course. And the other problem was that there was a watchtower, a German Watchtower about 10 metres away. So this is really not a good situation. So the men decided that they'd push on a head anyway. Bushell had I mean, his original plan was to get over 200 men out, so in the end, they managed to get 76 men out before a sentry noticed steam rising from the, from the tunnel entrance. And, you know, that happened when the guard had sort of actually just gone to a nearby tree to relieve himself. So, it was bad luck.

LAURA THOMAS: Slightly by coincidence. So 76 of them escaped via one tunnel. What happened to the other two?

NEIL SHARKEY: One of the tunnels had been discovered earlier. And then the third tunnel was used to store the sand because one of the big problems they had with these tunnels was hiding all the sand. Because the topsoil of the camp was like a dark grey. And the sand under that they were tunnelling through was like, yellow.

LAURA THOMAS: So they had to move it from...

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, so it was really hard, as soon as they had to, they had a lot of difficulty hiding this yellow sand because it was obvious that once it started appearing around the camp that, you know, tunnelling was going on. So in the end, they started hiding the sand from Harry into, you know, the, to the other tunnel.

LAURA THOMAS: I can't imagine how disappointing it would have felt to have put all this work into it and fall five metres short. But as you said, Neil, 76 did escape and James Catanach was one of them. So what happened to James once he escaped, where did he go?

NEIL SHARKEY: He travelled by train, and he went with three companions to Berlin. And then on to Hamburg. And then on to a naval town of Flensburg, which is on the Danish border. So so far, so good, they made pretty good progress. Where they were going, where James and his companions were going, is they were trying to get to Sweden, which was a neutral country. And so they needed to get to the Danish border, get through occupied Denmark, and then on to Sweden. Now, as they neared the border, you know, there were some policemen that became suspicious, and insisted on carefully examining their papers. And they also checked their briefcases and this is what gave them in a way, because they contained newspapers and escape rations. And that was, you know...

LAURA THOMAS: A pretty clear giveaway.

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, like the newspapers, I guess, had, you know, maps and railway timetables, and you know, that that kind of thing. And just, I guess they were just keeping up with, you know, what was going on with that, the hunt because when 76 men escaped from prisoner of war camp, everyone is looking for them. Everyone is looking for them. And that was perhaps part of the problem and when the police I mean, the other thing that gave the men away was when the police actually looked closely at their clothes that they wearing, they realised that the clothes that they were wearing were altered uniforms. Like they'd sort of you know recut their greatcoats. And that really gave them away in the end. And yeah, look, and they were thrown into prison. And what happened next is is quite tragic. On the 29th of March 1944, they were interrogated. You know, it seems non violently but it was pretty intense. But then the prisoners were handcuffed and loaded into three cars, and five Gestapo officers from the nearby city of Kiel took them for a drive. Now, the Gestapo names were Walter Jacobs, Hans Keller, Johannes Post, Franz Schmidt, and another guy called Oscar Schmidt. They weren't related. Schmidt is a common name in Germany. Now, Catanch went with the leader, Post, he was in the first car in this like, this little...

LAURA THOMAS: Convoy?

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, like a little convoy. And they sort of drove out into the countryside. And then there was a curve in the road, you know, Post went around the corner, he stopped the car, and told Catanach to get out. And Cattanach got out and, you know, was just told to cross the road into a meadow. And then once he did that, Post drew a Luger pistol from his pocket, and he shot him in the back. The Germans later said, In witness statements that sort of, you know, Post hid the gun, as the other cars came around the corner. And then they were told to get out of the cars, you know, probably thinking, 'Oh, gee, what's going on here?' And then one of them saw James's body on the ground. And then once that happened, they knew that they were in big trouble. And, and look, it was it was, it was pretty chaotic scene, by all accounts, but suffice to say, the other three men were killed in pretty short succession. Now, unfortunately, this was not the only time that this happened. This happened. in other parts of Germany, this sort of same scenario was repeated. And in all, 50 of the 76 men that escaped was shot, more or less in this way. So you know, the victims came from everywhere, you know, there were 20 Britons, there were six Poles, six Canadians, five Australians including James, there was a Belgian, Czechoslovakian, aFrenchman, a Greek and a Lithuanian. So basically all the different groups that were represented in the camp, and had taken part in this escape, you know, fell victim to, to this war crime. You know, it was a war crime that the men had been recaptured. They were in custody, they were no threat to the Germans. So this was a punitive measure by the Germans to, you know, I guess, to send out a message to the other prisoners in the camp not to do this again. So yeah, I mean, the British government learned all about this, when the Swiss authorities visited the camp, and the Germans said, oh, yeah, 50 men shot whilst trying to escape. So this was kind of the this was the line that they used.

LAURA THOMAS: Did the 26 others survive? Or did they made a similar fate at a separate time? What do we know about them?

NEIL SHARKEY: Okay, so of the 26, three actually succeeded in escaping, so two Norwegian prisoners, managed to escape into Sweden. So they're actually sort of a group that was sort of those two men were a group that was closely associated with James and the, and the other four, you know, they'd sort of, it's just that these two managed to escape being rounded up, you know, but they were all sort of more or less travelling together. And then there was another chap, a Dutch guy who managed to get into occupied France, and then he made contact with the resistance. And he was brought south, he ended up in Spain, which was neutral too. The rest of the men were were primarily captured by the Luftwaffe itself, rather than the police or the army or the SS. And so if the Luftwaffe sort of rounded you up, then they would just sort of quickly just get you back into the camp. Those men were were pretty lucky, but but some of those other men, some of those 26, were rounded up by the police and so forth. It's just that Hitler and the Nazi authorities had actually decided that they were going to kill 50 men. You know, and it's not accidental that this was actually, I guess, luck played into it. Also. There were actually six Australians that took part in the escape, but one of them was among those, you know, the 23 that were recaptured, but not killed.

LAURA THOMAS: Yeah, okay. We have a few of James's items on display, as you mentioned earlier, Neil, but I wanted to talk specifically today about the language certificate. I think that's a really interesting item. What is the story behind it?

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, the certificate is really interesting. It indicates that James passed associate stage one in Norwegian.

LAURA THOMAS: While he was in the camp?

NEIL SHARKEY: While he was in the camp. So yeah, he was studying Norwegian. Now, it's a funny language choice, isn't it? You know, I don't want to disparage Norwegians or Norway in any way. Absolutely not. But it's uh, you know, you'll agree it's an unusual choice for anyone to, to study. I guess generally, at that time, people would, you know, if they were going to learn a language, they'd learn French or German. Yeah, maybe ancient Greek or Latin if they were of an intellectual sort of persuasion, I suppose. I mean, a lot of guys from the British Empire countries, they'd probably be more likely to learn Hindi or Swahili or Pidgin than Norwegian, you know, it's a pretty unusual one. But James, you know, clearly had a reason for studying Norwegian. And I think it's pretty easy to surmise that he was learning Norwegian, because he thought it would help him in his escape. Because Germany at this time, was full of Norwegian guest workers that had been brought from occupied Norway to Germany to work in factories, and so forth. And I think that is why he was learning Norwegian. And that's why with the men, he was travelling with two of those men were Norwegians, in fact, and one of them was a New Zealander, but a New Zealander whose parents were Danish. So James, I think, pretty wisely, he was travelling with a group of men that he thought offered him a very good chance of escaping, because, you know, the, as I explained before, you know, the two men that did get away were Norwegian, and one Dutchman, so, the guys, the only guys that, you know, managed to escape in all of this were guys whose nationality was plausible, you know, it was plausible Norwegians or Dutchmen to be in Germany, because they were from occupied countries, whereas, you know, you know, British people, or, you know, people with accents from, you know, Australia or England or whatever, it'd be very obvious.

LAURA THOMAS: You'd stick out for sure.

NEIL SHARKEY: Absolutely. They were the first guys to give themselves away. So James, I think all things considered, he prepared himself very well, like by, by all accounts, he was very good German speaker, but his German probably wasn't good enough for him to pass himself as a German. So he thought, well, if I pass myself as a Norwegian, that might fool the, you know, the Germans that are looking for me, but yeah, unfortunately, it didn't work.

LAURA THOMAS: And am I right in saying the certificate arrived back in Australia, after he had died?

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, yeah, that is right. Yeah. It's like a, like a lot of these things. It's like the article that, you know, was published in the paper after he was captured. Another exhibit we've got is the telegram that was first sent to the family, telling them that he was a prisoner of war. Now, that didn't arrive for you know, a couple of weeks after his plane was shot down. So and when they got that, that Telegram, they were thrilled because they thought, oh, wow, he's alive. You know, he's in a prisoner of war camp. He's done his duty, he can just stay there, he'll be fine. And you know, when the war's over, he'll come back to us. So unfortunately, that didn't turn out to be the case.

LAURA THOMAS: Neil, I'm interested to know what drew you to the James Catanach story. Why do you find it so interesting?

NEIL SHARKEY: Oh look, it's it's the subject of one of my favourite war films, not James specifically. But this escape, which is known as The Great Escape. And that was a film that came out in the early 60s by that name. And it's, you know, it stars Steve McQueen, and Richard Attenborough, James Garner, and just a lot of great actors. It plays around a lot with the truth. Like, you know, there's motorcycle chases, and there's a couple of the guys steal an aeroplane, you know, those things did not happen.

LAURA THOMAS: Typical Hollywood kind of situation. ,

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah but look, where it is really accurate is what I was talking to you about before, as, as far as the really clever things that the men did, you know, like the disguises they made, the techniques they used to dig the tunnels and to light them. This one great scene where one of the chaps comes into the to the bunkhouse and he just jumps up on top of his of like, a triple bunk, I think, and he just falls right through, falls through you know, because what's happened is someone has come in and taken you know, every second...

LAURA THOMAS: Oh the slats

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, the slats on the bed. So, you know, he's, and he's just, he's just like falling through this because you know, that all the timber that they needed to shore up these, these tunnels. And now all of that is pretty much spot on as to what exactly happens. So I guess, you know, having the film which is something I first watched, probably when I was nine, or maybe even younger. That's like the starting off point to you know, like my own research and finding out more. And in fact, when I first found out about James and met his family, I was just absolutely thrilled, you know, just to just make contact with a family and, and look and handle the objects of someone, you know, that had been involved in that event. You know, I mean, it was just such a amazing privilege and honour to be in that that situation. And, you know, the more I came to learn about James, and some of his friends, you know, it really brought home the tragedy of this event, you know, that these, these guys were doing, I guess what they thought was the right thing to do what, you know, they'd been told that they should do as you know, that was the honourable thing to do. If you're a prisoner, you try and escape you try and make things difficult for the enemy so that they tie up resources looking for you. But yeah, that price of the 50 men killed is just I think, you know, far too high.

LAURA THOMAS: It's a tragic, tragic story, but drives home the work that you do here at the Shrine Neil in sharing these stories and educating the public on what happened and that history can never repeat itself in that sense. So thank you for, for sharing this story. I appreciate you coming in.

NEIL SHARKEY: Yeah, sure. Well, I'd like to think that history won't repeat itself. But you know, I mean, unfortunately, but yeah, yeah. No, it's no, it's a pleasure to to be with you here, Laura. And to talk about James Catanach, or Jimmy, as I, as I like to call him.

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks for listening to this episode of the podcast. When researching the story, I also spoke with James Catanach's, Julia Burgess. And here's what she had to say about her uncle and what it meant to have his story on display at the Shrine.

JULIA BURGESS: Well, I think it's important that everyone knows the horrendous thing that wars have. And I think, you know, this Shrine is the most amazing place. And it's, you know, it's a place where I know a lot of people come and our families are very happy to have Jimmy's story here.

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks to Julia for her support in this podcast and to Neil Sharkey, for sharing his research with us. If you'd like to hear more about the objects we have on display, search Shrine Stories wherever you get your podcasts

Updated