- Conflict:

- Vietnam War (1962-73)

The Shrine Stories podcast takes you on a deep dive behind the objects on our gallery floor.

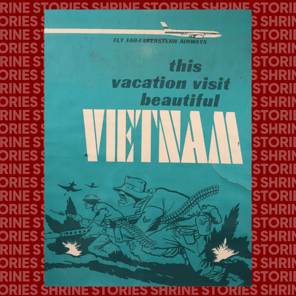

In this episode, we explore a poster on display in the Vietnam War section of our Galleries.

The poster was originally made and distributed in the United States as a protest piece. However, the one hanging at the Shrine has been re-designed and adopts a whole different meaning despite its similarities to the original. Join the Shrine's Collections coordinator Toby Miller as he unpacks this story.

Music

Across the Line - Lone Canyon

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance embraces the diversity of our community and acknowledges the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation as the traditional custodians of the land on which this podcast was recorded. We pay our respects to elder's past and present.

Welcome to the Shrine Stories podcast, a place where we take you on a deep dive into the stories behind the objects on our gallery floor. My name is Laura Thomas and I’m the production coordinator here at the Shrine.

In this episode of the podcast, we’re delving into the story behind a poster on display in the Vietnam War section of our Galleries.

The poster was originally made and distributed in the United States as a protest piece. However, the one hanging at the Shrine has been re-designed and adopts a whole different meaning despite its similarities to the original.

Joining me to unpack this is Collections Coordinator at the Shrine, Toby Miller. Welcome Toby.

TOBY MILLER: Hi, Laura. Happy to be here.

LAURA THOMAS: Before we get into the details of the poster, I want to start by speaking a little bit about protest and opposition around the Vietnam War, because this poster was essentially born from a protest poster. So Toby, can you please explain the context of public sentiment when Australia first entered the Vietnam War, and then how this changed over time?

TOBY MILLER: Thanks, Laura. It's an interesting question. I think most people have a view that there was opposition to the war right from the start. But that's not the case. In the early days, and in fact, right through most of the war, the public did support what the government was doing. And they also supported the return to conscription, which was introduced in 1964. That was supported both by the general public and often by the people who were being conscripted. It did change, however, over time as the war progressed, and as more information became available, there was resistance to both policies. And by the early 1970s, the government was pulling back the opposition was steadfast against the war, and there was general opposition building within the community that would lead to wide public protests.

LAURA THOMAS: And why did this public sentiment change? Was it because we were getting more images and pictures from the war? Or can you explain that to mToby as to why there was a shift over time.

TOBY MILLER: We certainly were receiving more images and more information about the war, certainly more real time. The Vietnam War is often referred to as the televised war, the first war where people could see the action for themselves nighty on their TV screens. Perhaps the sort of the watershed moment were photographs that came from America relating to a massacre of civilians, in the little hamlet or village of My Lai, those images, galvanised opposition in the United States, and that followed through to the Australian public.

LAURA THOMAS: Now, we've already alluded to the fact that this poster was used as a form of protest. But what other means were used to protest the war at that time?

TOBY MILLER: Well, in Australia the most public acts of protest would have been, people called up in the in the draft, these were 20 year old men, they had their birthdays pulled out of a lottery system. And they would have been, or there were certainly were some cases of individuals who did not want to, did not want to serve their time in the army. And they were highly publicised because those individuals, they had to go to court, and if they were unsuccessful, they either had to serve their service or they were imprisoned. And I think those sorts of actions taken by the government were enough, I think, to shift public sentiment, particularly amongst the younger, younger demographic, the people that we call baby boomers today, they were they were the younger demographic at the time. And I think they were part of pushing an anti-war protest, and that was picked up by other groups that were critical of, at the time, American imperialism, and that tied into really a worldwide movement in many countries, many, many democratic countries that people pushing back against what they saw as American imperialism.

LAURA THOMAS: So let's talk a little bit about the poster now. Now the one we have on display at the Shrine is actually based off an American version of this poster. So Toby, let's talk a little bit about the American one. What Some of the key features of that one?

TOBY MILLER: Well, we believe the American poster was produced in about 1966 by a small printing firm called Pandora Productions. We believe that that included David Nordahl, Dean Kanter, and Bart de Malignon , and they were based in Minneapolis, and they spent most of their time producing concert posters for, for bands like The Doors or Frank Zappa, Jimi Hendrix. They were well known for printing using fluorescent inks, which then when the posters were seen under a black light, that's a UV light, the poster would fluoresce. So it's very much they had a real style very much in the 60s of that radical 60s of that sort of psychedelic vibe. They produced two versions of this poster: one that was seen in red, and the other in a, in a teal colour. The poster has two US soldiers at the bottom, they're running through what looks like a field, they're carrying their weapons. In the original poster, there's planes dropping bombs and explosions behind them. And as you sort of scan the poster upwards, you see in very large lettering, the word 'Vietnam' and then a little tagline, 'This vacation, visit beautiful Vietnam'. Then above that, there is sort of a parody of a airline logo, fly far, far eastern airways. So it looks if you read it from the top down, it looks like a commercial travel poster advertising what should have been, you know, an exotic destination. But when you look at the details of what they're showing you, travelling to Vietnam during the 60s, particularly if you are a US, a US soldier that was obviously going to be a very harrowing time. So it's using humour, it's using the visual language of commercial travel, it's trying to probably then capture an audience and surprise them and try and bring the reality of the war back to back to people.

LAURA THOMAS: So it's very tongue in cheek in its sense, and in essence, it is kind of a maybe a more gentle protest piece.

TOBY MILLER: Yeah, there are certainly posters that try to shock people with photographs or facts. There were lots of poster has been produced, remember this is the hippie generation, there's lots of posters with doves trying to point to a different way. There's lots of very overtly political posters that reference politicians and senators and, and like we were talking before, this ties into a lot of the music that was being listened to produce particularly in America, but also in Australia that references the Vietnam War, particularly the way it affects the youth.

LAURA THOMAS: So how do we go from this anti war American poster to the one that we have on display here at the Shrine?

TOBY MILLER: Well, that's a mystery. And like lots of objects that we receive, this one was donated to us by a member of the public, it didn't come with a lot of backstory. The donor was a national servicemen. He was called up in 1968. And he arrived in Vietnam in late 68. And served his tour right through to the end of 1969. And a few years ago, he was sorting through things in his garage and he found this rolled up poster, he didn't know what to do with it. So he came to us and we were glad to accept it because our our holdings of the Vietnam War, we have a large poster collection here at the Shrine but they are mainly Second World War posters, and a few more recent ones, the ones that we find hard to come by are Vietnam posters of Vietnam era posters and and First World War posters. So we were very pleased to receive it, initially, and not unsurprisingly, thought that it was a anti war poster, that it might have been connected to the moratorium protests which took place both in America but also here in Australia and the most popular one in Melbourne in about 1970. We thought it might have been part of that. We've collected and we've been actively collecting moratorium badges, so people were wearing badges to show their disapproval at the at the war.

TOBY MILLER: We hadn't seen too many posters, but we know that there are some official moratorium posters and there's one or two additional ones that were produced during that time. But this one was an oddity and like lots of things that we receive, we then conduct our own research and it was in researching the poster we came across the American one. Initially, we thought it was a version of the American one and it would not be out of the ordinary for an Australian servicemen in in Vietnam to have things that were brought there by American soldiers. This particular donor had some other things that Americans had given them, they did interact, there was quite an exchange programme. But on closer inspection and on conducting more research, it was evident that this poster was not an American one, that there had been alterations made to the image. In particular, the two figures in the original one, the soldier's Chevron's point up towards their shoulder, which is how the American uniform has it, but in this version, and they point down towards the lower sleeve, which is the Australian uniform and the iconic sort of US GI steel helmet is replaced with the less well known but equally iconic in the Australian context of the giggle hat, the small fabric hat. So it's clear that this poster had been made either by Australians or deliberately for Australians.

TOBY MILLER: Another interesting fact of the poster on closer inspection is it's not produced by an offset lithographic process. That's the commercial way to produce posters, most of the posters you would see would be offset lithographs, so they're designed and then printed. This one seems to be hand printed. And so when we were researching it, we looked around for other versions, and we did find a couple there. There's one or two now at the Australian War Memorial, and they identified the draughtsman, the maker of the poster as an Australian Corporal who'd been in Vietnam as part of the first topographical survey troop that was a particular unit within the Army that had been sent to Vietnam to produce maps, basically, to to, to take the existing maps and to reproduce them and to distribute them for tactical operations. Obviously, things were changing a lot at the time, and the army needed up to date maps. And we know that the survey troop during that time did operate a lithographic press at the camp at Nui Dat. So they would have had the means to produce the poster.

LAURA THOMAS: So is it assumed that ours comes from the same person or the same group that were making these?

TOBY MILLER: We've located maybe six or seven versions, not more than that, they're all closely related to people who served in the survey troop or who were in Vietnam or have some service associated with it. We can't say for certain that it was produced in Nui Dat, although there's sort of anecdotal details that at least one of them was brought back and printed in Vietnam by a member of the lithographic troop. After they served their time in Vietnam, these members, they were all members of the permanent army, they weren't doing national service, they returned to the lithographic Squadron, which is based in Bendigo. So they would have had an opportunity to continue to produce posters. So it's really a question whether it was made in Vietnam, the fact that this was donated to us by someone who served and had no association with the permanent Army or the troop means it's possible, although of course, when they returned from service, they also spent some time on camps and base camps here in Australia. So they might have picked it up then. But it seems quite clear that it wasn't produced for public consumption, it was produced by the soldiers, they'd obviously had access to the American version, they felt that there was a good cause to reproduce a version that spoke to their own experience, it was shared amongst troops. And and in that sense, it makes it somewhat more unique and certainly more relevant to our collections and the original poster.

LAURA THOMAS: And you mentioned that when you first saw it, you thought it was of a similar vein and an anti war kind of protest poster. Has that now changed? Do you have a different view of it on further research?

TOBY MILLER: TOBY MILLER: Yeah, I think we certainly have a more nuanced understanding of how it came to be and who it's trying to speak to. I think it does make a difference that it's speaking to the experience of Australian soldiers. The fact that we believe it was produced by soldiers and consumed within their sort of as an audience does give it a different sense. I think the anti Vietnam sentiment that we were talking about before, I think it was different within the Army. And without, we know from the conversations that we have with people who were national servicemen that they they are, in many ways proud of the service that they were able to give even though it was difficult, and I think a lot of them, you know, would rather not have had to serve or or to experience the things that they did because it was very difficult. It was a very difficult challenge for people they were they really, we haven't done it before in Australia and we haven't really done it since. We haven't taken people by lottery and asked them to go and fight overseas. So I think that this is what this poster is trying to capture is is, is more of that laconic humour that is that is characteristic of Australian soldiers right through from probably the Boer War through to today. It's a it's a pressure valve, it's about the way soldiers operate within the Army and their own views of that. I don't think it I don't think people would have used it to express clear political or personal opposition to the war. I think it's more a way of working through the very conflicted emotions that people can have in service - Their difficulties about it, it's about coming to terms, coming to terms with that, and finding some way to have ownership or be at peace with the service that you do render.

LAURA THOMAS: And as you mentioned, the fact that it was well, we think it's potentially made on the field by permanent soldiers rather than those who were conscripted. And it wasn't mass produced.

TOBY MILLER: No, I think I think, I think in order to produce it, it would have been probably hand drawn or altered photographically, and then I think they probably were testing it out, rather than producing it on mass. They did produce posters and things that were used by the army, for various reasons. But I think this is an unofficial poster. That's how it's described by the War Memorial. And I think they get that right that they produced a number of copies, and it was shared around to other soldiers who could who could relate to it.

LAURA THOMAS: Why Toby do you think it's important for people to visit the Shrine and see this poster?

TOBY MILLER: Thanks, Laura. That's another great question. Obviously, we want people to visit the Shrine and to look at all the artefacts. But if we are to single out this one in particular, I think, as we've sort of discussed it, it occupies a place in between the well known protest anti war movement and the experience of the soldiers who were in Vietnam. We know subsequently, that it was very difficult transition out of the army for a lot of these soldiers, in particular, the national national servicemen who didn't have a regular Army post to return to, and I think for a lot of them, they returned and were told, I think in quotes, you know, to 'melt away' to go back into, into the general population. And that was, that would have been difficult under any circumstances. But when the anti war movement had had reached the point that it had, by the late 1960s, early 19 1970s, I think that they had very little connection, either to the army or to the community.

TOBY MILLER: So I think, when we look at a poster like this, and we start to tease it out, when we say, when we try not to look at it as simply an anti war poster, but a poster about the war, something that expresses the soldiers view, I think we can find points of connection there. And if we can show items and speak to that we can try and, and be nuanced, then I think as as a population, as a community, we can start to create the space that that wasn't there, originally, that we know, a lot of those serving soldiers have suffered as a result.

TOBY MILLER: And one of the reasons or perhaps the reason for the Shrine today is to create a space and to share information and to try and bring all those sectors of the community back together, and to speak truthfully, about the experiences of, you know, the the war in Vietnam is multifaceted, in a lot of way. And I think when we try and simplify it with anti war on this side, or soldiers doing this on, on that side, we fail to capture what all those different voices are really saying, when they speak together about the complexities of that time. There's no doubt, I think, in hindsight, that there were lots of errors of policy that contributed throughout the 60s in a whole range of issues. But when we go down to the personal level, and I think at the Shrine, we're always we're always at the personal level, even though we're dealing with with large, impersonal stories. At that personal level, we need to be able to identify the actual experience, and try and communicate that.

LAURA THOMAS: Thank you so much, Toby, for those reflections and for sharing some more information about this poster today. It's been fascinating.

TOBY MILLER: Thank you. Thank you, Laura. It's been fun.

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks for listening to this episode of the Shrine Stories podcast.

The Shrine Stories podcast is released monthly, so to discover the stories behind more items on display in the Shrine’s galleries, search for ‘Shrine of Remembrance’ wherever you get your podcasts.

Updated