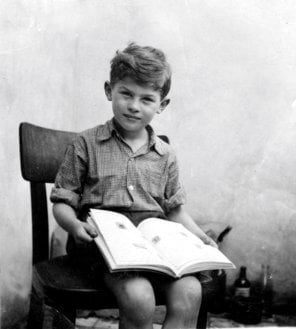

Garry Fabian was just eight years old when he and his parents were interned at Theresienstadt - a ghetto, concentration camp and transit camp used by Nazi Germany to house Jews from across Eastern Europe.

Of the 15,000 children who went through the camp, only 150 survived.

Listen as Garry shares his story and reflections on his childhood.

Music

If I Were You, Alsever Lake

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance acknowledges the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation as the traditional custodians of the land on which this podcast was recorded. We pay our respects to elders past and present.

Welcome to the first episode in the Toys, Tales and Tenacity podcast series. In this series, we will be delving into three stories of how war and conflict have impacted the childhood of three quite extraordinary individuals. Our first episode takes us to Theresienstadt - a ghetto, concentration camp and transit camp used by Nazi Germany to house Jews from across Eastern Europe. Of the 15,000 children who went through the camp, only 150 survived. My guest today, Garry Fabian, was one of them.

Garry was just eight years old when he and his parents were interned at Theresienstadt and lived there until they were liberated in May 1945. Garry joins us now to unpack his experiences and his message to future generations. Hello Garry and thank you for joining us…

GARRY FABIAN: Good morning.

LAURA THOMAS: Now, Gary, I was hoping you could start by telling me a little bit about your childhood before the war broke out, what was it like?

GARRY FABIAN: Now, of course you realise that'll be sort of a something I learned in detail later. Because, you know, when you're a very, very small child, the world is totally different

LAURA THOMAS: Of course. Of course.

GARRY FABIAN: Well, I was born in Stuttgart, in Germany in 1934. Now, just to give you a link to our family and Germany, on my mother's side, I've traced them back to 1290 in southern Germany. On my father's side, I've traced them back to 1602. They lived in a small town in East Prussia, which is now in Poland and in the town Chronicle, in 1602, there's an entry that Jew Fabian was allowed to buy land for some services he did to the gentry. Now, that was most unheard of in those days - Jews owning land. Now, my grandfather on my father's side, lived in his town until he was a young man, then he went to Berlin, where he married and lived there. He died in 1935. So the family goes back 700 years.

Now, in 1933, of course, the Nazi's took over the government and things got a bit unpleasant. In 1935, there was Nuremberg laws where Jewish citizens are deprived of citizenship, they're very restricted, where they could work. And as time went on, these things accelerated, not in a good way. Now, in 1936, my parents and my maternal grandparents decided this was not the place to live after all these centuries. So they looked around, where to go. And there was inquiries here and everywhere. Eventually, they bought a small business, in the Czech Republic, in what was a German speaking enclave in Sudetenland. Of course, in September 1938, when, after the infamous Munich Conference, the Germans took over the Sudetenland and remember vividly, I mean, obviously, I didn't understand the implications, but I vividly remember, we're sitting down at lunch, and my late father rushes in and says, 'The German will be here in four hours, we've got to leave'. Now, obviously, the implications didn't register at that point, but I mean, to a half year old, dinner on table is far more important than global politics. So my mother and myself are rushed to the railway station, my father said, 'Look, I've thought a few things come, I'll come later'.

LAURA THOMAS: So eventually, you ended up in Prague during that journey, but that was quite a long journey. So talk to me about that and where you had to go to then end up in Prague.

GARRY FABIAN: Actually, that's a sort of interesting sideline, because at that point, everyone wanted to see documents. My father caught up with us in Moravia In Bruno, we met up with a gentleman who actually worked for the business previously, that we had in the Czech Republic. And now he also was a sort of, in bit of trouble, he was a very keen communist, which wasn't exactly the flavour of the month then. So with him, and our little car, the five of us, actually, the six of us squeezed in, and we drove towards Prague. Now, as we got closer to Prague, there's a roadblock and they wanted to see documents, and this fellow we said, 'What what happens now?' and he said, 'Look, leave it to me'. So the policeman came to the car, he said, 'Look, no good asking that lot, their relatives from a village that wouldn't know what you're talking about'. So he's sort of led us through and then we got to Prague. And we found a room where the family sort of gathered, which was the five of us, my grandparents, my parents, myself,

GARRY FABIAN:: I mean, it was sort of very precarious, if you like. I mean, we had no papers. And basically, we were illegals. And as situation tightened, authorities got much more strident, you know, what was going on? So here we were, and obviously, my father couldn't take a proper job, because he had to have papers. So he finished up, we still had the car then, so he finished up driving messages for a gentleman who I suspect, considering the situation sort of paid less than normal where wages would be concerned.

LAURA THOMAS: I can imagine that's very true

GARRY FABIAN: Then, the Jewish community there, tried to as far as possible, to sort of help all these new immigrants. And my father got a job in the medical store, because when they moved to the Czech Republic that bought a small factory for surgical instruments, so he had some connection with a trade. So that was, you know, that sort of provided a meagre living, On the 15th of March, we were actually in the streets when the German army marched in.

LAURA THOMAS: What do you remember of that? You would've been quite young still.

GARRY FABIAN: I remember it vividly. Look, the thing is, that, to this day, when I sort of think of day, it really, a sort of cold shiver goes down my spine, you could feel the the aura of evil emanating from these marching troops, which of course later proved itself to be valid.

LAURA THOMAS: So even if you didn't necessarily understand exactly what was going on, you still felt a sense of fear, a sense of dread.

GARRY FABIAN: That's right. I mean, at the time, I was not five. So yeah, when you're an adult, you've got sort of a view back history of normal life. When you're a kid, you know, it's not right, but you take it day by day.

LAURA THOMAS: So while you were in Prague, did you experience discrimination? Or were your family trying to make life, in air quotes here, normal?

GARRY FABIAN: Well, of course it's discrimination. You couldn't go to certain places. Jews weren't, there was no schools for Jews. In fact, I remember one incident, a friend of mine, and we're walking down the street, and a group of probably 16, 17 year old SS youth started sort of assaulting us. And they called us names and they sort of started hitting us now. I've always been brought up to stand up for myself. Unlike a lot of other children, Jewish children, they were saying 'I never fight back'. Anyway, at the end of the day, I got a hell of a fright. I got few scratches and a couple of bruises. My friend had a broken nose, two black eyes and some other things. So that was one of the thing. But the other thing of course, there was no school for Jewish children. So we drifted around and then in about 1940, they grudgingly allowed a sort of small school, Jewish school at the Jewish Community Centre. And our playground was the Jewish cemetery that goes back 1000 years. I mean, I don't think we learned very much. But our teacher was, I remember him, I can't remember his name. He was a redhead with a very, very strong temper. But whether we've learned anything useful, I don't know. But I'll tell you what it did do. He instilled in us a pride of our sort of heritage, which perhaps gave us some sort of backbone, that even for those who didn't survive, it was something there. Now, we've got to get some history into this. Some parachuters from the Czech army in exile, came to Prague, and assassinated the Reichsführer. And then things got really worse. And then the Nazis decided to clean the country of Jews. They set up the ghetto in what was a town called Theresienstadt, which Theresienstadt is just about 50 kilometres from Prague, a military establishment going back to the 1700s. So if you visualise, small town, it was surrounded by walls and barracks and a sort of town in the middle. And just to give you a feeling of lack of space, in normal times, that town had a population of about 3500. During the four years from 1941 to 1945, at any time, there was about 30 to 40,000 people crammed in that place.

LAURA THOMAS: So when your family went from Prague to Theresienstadt, what was that like for you and your family? What was the process of that?

GARRY FABIAN: Well, initially, you were all sort of corralled in a sports stadium for a couple of days. And then eventually, you're taken to the railway station. And unlike the transport east, we did go in a normal passenger trains. But then we got to a place about three or four kilometres from Theresienstadt. At that point, the rail did not go into Theresienstadt. It was built in about '43. And then everyone packed up their one little case they're allowed to take and there was a sort of a two hour march through to Theresienstadt. Now, once you got there, you sort of went through some registration process. And like, you know, the Germans are very sort of fond of paperwork, and then you got allocated to different barracks. I was initially in the children's barrack. And men and women were in separate barracks. Now eventually, as I said, my father was in charge of medical store, and we got a room in that barrack, sort of room above the shop. So in some ways, we're privileged, but the privilege, the so called privilege, every so often, the whole lot got shipped off and three of them, I don't know what their title was, the head of the Jewish Council were put up against the wall and shot. So I mean, it's a very precarious thing.

LAURA THOMAS: How old were you at this point, Garry?

GARRY FABIAN: Eight

LAURA THOMAS: At eight years old, what's going through your head? Or are you again, like you said, you don't have a point of difference?

GARRY FABIAN: Well, by that time, having all these experiences of having to move and having seen troops, I had a fair, sort of understanding of the world in a limited way. But I knew this wasn't the way life should be. Of course, the other thing was that my grandparents were shipped off to the Theresienstadt in June 42. By the time we got there in November, they'd been sent East and killed. So we never ever caught up with them again. Look, when we got there, as I said, if you've got a place that sort of 2500 people normally reside in, and you've got 30-40,000 people in, you're in barracks with three tier sort of bunks with straw mattresses. In fact, I caught the measles and whooping cough and something else. But when you're a kid, you know it's not normal. You live day to day.

LAURA THOMAS: You were young enough that you weren't working for a couple of years there. What, with no education, what what would you do to entertain themselves?

GARRY FABIAN: You drifted around, I mean, the best minds of Europe were there. So there's little sort of lessons behind corners and things. And of course, a couple of things happened that there was two things one of them there was a children's opera, Brundibar, which the Nazis encouraged. And the other one there was a, an opera, the Emperor of the Ghetto, which had one performance, and then they woke up that basically it was a satire on Hiltler so that was automatically sort of canned. I mean, there was sort of food was very minimal, medical, although the best doctors in Europe were there as internees, supplies were limited. And when you turned 10, it was a sign you had to go to work. Now I was working in the tailor's shop. But look, this probably sounds in a normal world totally illogical, that one of main production was mending German uniforms that came off the eastern front. Now, as I said, this probably is totally irrational to normal people. Whenever we saw a couple with bullet hole in it, we said 'Oh good, there's one less of them'. I mean, in a normal life, this is totally ridiculous.

LAURA THOMAS: But it wasn't a normal life.

GARRY FABIAN: Then, oh, yes, in 1944, something very, very strange happened. Suddenly, the camp was beautified. There was sort of cafes open and concert halls open. It was all a sham, all rubbish. And then 1944, a delegation from the Red Cross came, the Germans arrived to show the world how the world of Jews were treated - marvelous. And they there five hours, shepherded to see what they were supposed to see. They wrote a glowing report and went off again. And they made a propaganda film, which was total fantasy. I mean, none of it was real. They had sort of playgrounds, and they handed out ice creams to kids. And then when the camera went away they all got smashed again. It's sort of one of those unreal. So as I said, I didn't know about this film for about 50 years. And then some friends were in Jerusalem, they were shown the film, and they rang me when they came back and said 'Look, I saw this film, you should get a copy of it'. Anyway, there was a football game going on, all staged. And they sort of pan the audience. And for about 15 seconds, there's a close up on a kid. And he's sitting here now.

LAURA THOMAS: You're looking at it saying 'That's me'.

GARRY FABIAN: Yeah it's just one of those weird, weird, weird stories. And the other statistics which is probably relevant, that during the four years 15,000 children under 14 went through the place. I mean, basically, Theresienstadt was not an extermination camp, it was basically a transit came. Anyway, 15,000 kids under 14 went through. At the end of the war, and the figures are a little bit rubbery, some figures say 140, some say 150 are still around. So the odds of me being here a very, very, very long.

LAURA THOMAS: It's it's absolutely devastating. But you've spoken before about this and do you think it was to do with your father's position in the camp and what he was doing?

GARRY FABIAN: Look, the position of, there was the Jewish Town Council. I mean, they're basically supposed to administer but they had no authority. I mean, the SS really were the overlords. And every so often, all those people in charge of things got shipped off to Auschwitz. So look, the odds, whether it was luck whether there was something more to it. But then, of course, Theresienstadt as I said was a transit camp, and every so often, transports of 1000 got shipped off to the east. Now, we never knew until March 45 what was happening because we were told, they're being relocated in other labour camps, you know, to aid the war effort. Now, March 1945, when the Red Army started coming further west, the Nazis liquidated a lot of concentration camps, they had the death marches, and shipped a lot of the previous people back to Theresienstadt and some of them had been there. And that's when we found out what really was happening.

LAURA THOMAS: So Gary, you were 11 and a half when the camp was liberated?

GARRY FABIAN: Yeah.

LAURA THOMAS: What do you remember specifically of that time, and how did you feel during that time?

GARRY FABIAN: Well look, obviously, I mean it is a total relief. In fact, in some of the talks, I say my real birthday is on the 8th of May 45, because that was the new life. But roundabout, about the middle of 1944, we knew something was happening, because that's when the Americans started daylight raids over Germany, and Theresienstadt was in the flight paths. And every lunchtime you see these hundreds of, of black aeroplanes going over. On the fifth of May 1945, in the night, there was a lot of shooting and noise and all that. And then we woke up and it was totally quiet. And all the Germans, the Nazis had gone. So we all crowded around the streets. And all of a sudden, there's a very loud noise heard in the distance, and everyone panicked. Oh, no, they're coming back. And three Soviet tanks rolled into the camp. I've never ever, I don't believe there was ever three Soviet tanks had a bigger welcome than on that day. When the Russian army took over the camp for about a week, because then the Red Cross came in. And, of course, the transports on the east brought back typhus. And 3000 people died after liberation. So we couldn't leave there till July because it's quarantine because of health reasons. And there was this weird sidelines, that probably doesn't make sense. But some of the people, sort of the inmates or whatever you call them, went out in the countryside, andone of them brought back a horse. And my father said 'What on earth do you want a horse for?' He said, 'I don't know, it's booty of war'. The other thing that a lot of the German, then prisoners of war from the camp, they came in, they sort of had uniforms with red spots, and they had to clean up things and do things. And once again, there was a- they actually had to have sort of guards because some of the inmates may have got quite violent.

LAURA THOMAS: I can imagine. It's understandable, isn't it?

GARRY FABIAN: And then, of course, where to go? Because obviously, going back to Germany, was totally out of the question because of what happened, it was under allied occupation and they didn't really want people coming in. So we went back to the town in Czech Republic we'd gone to the 1936. And then, of course, as I said, we had a little factory that the Germans confiscated, and then the Czechs confiscated it as booty, so there was no restitution as sort of ongoing thing for years, nothing ever happened. But the thing that was totally clear to us that Europe was no longer a place, after all that happened, it was just not feasible. So inquiries thrown out through the Red Cross. I had two uncles in, in Australia, who came here just before beginning of Second World War, my mother had a cousin in Brazil. So letters went out and all this. And now this is where time becomes interesting. The visa for Australia arrived on Monday, a visa from Brazil arrived the following Friday. Now, had it been the other way around. We may, not particularly you, but someone like you would speak to me in Portugese.

LAURA THOMAS: In a totally different language.

LAURA THOMAS: You're listening to the Toys, Tails and Tenacity podcast series, a place where we have conversations exploring the impact of war on children. This podcast links with the Shrine of Remembrance's exhibition Toys, Tails and Tenacity on at the Shrine until July 2024. My guest today is Gary Fabian, who was just eight years old when he was interned at Theresienstadt. We pick up now where Gary begins his long journey to Australia. So you've got your Australian visa, how did you actually get to Australia?

GARRY FABIAN: Now, it took about two years because shipping was at a premium and most countries used shipping to bring troops back and all sorts of things. Now our trip was very convoluted. We went from Prague for a few days, went from Prague to Paris where my uncle lived who had survived the war undercover and we stayed there a few days now. There was a little side episode. I still remember I was very cross about my parents were taken to see the Moulin Rouge, but I wasn't taken because I was too young to see ladies with little clothes on. And then we went from Paris by train to Grenoble, where an aunt and uncle of mine had survived the war under hiding, and from there we went by bus to Cannes on the Riviera. Now that itself was quite hair-raising. We go through the Pyrenees and going around tight corner, the bus driver, took his hands off the wheel, tucked his chin on the wheel and rolled a cigarette. Now 1000 foot mountain one side and a 2000 foot drop on the other. Now, obviously, our time wasn't up. Anyway, we got to Cannes. And we went on a ship from Cannes to New York, then from New York, we flew to San Francisco, which took two days on a DC3. And then we boarded the ship in San Francisco, which was a converted troop carrier, the Marine Phoenix, which, in many ways is symbolic, because like the Phoenix rises from the ashes, and then after three weeks, on the sea, we got to Sydney. And from Sydney, we got on the train that night and came to Melbourne. Now, I 'd learned rudimentary English from someone - thank you. Where's the next toilet? And anyway, quite frankly, I thought, 'I don't know. I don't think these people speak English' with an Aussie accent. Thr other thing that really struck me that, and this sounds totally trivial and ridiculous, that one morning, these two gentlemen, at breakfast, they had a grapefruit and started pouring salt and pepper on it.

LAURA THOMAS: So you're there thinking 'Where am I being sent people? People who put salt and pepper on grapefruit'.

GARRY FABIAN: It was quite a new world, but at one stage I really wished the ship would sink. Outside Fiji we ran into a hurricane. And as I said, we landed in Sydney, but because the trip went to Sydney, and then we went overnight, to Melbourne, and then sort of next question is, we found some lodgings or my uncle found them for us. And then of course, one had to go to school.

LAURA THOMAS: And what were your first impressions of Melbourne, and Australia as a child?

GARRY FABIAN: It was a totally different world. I mean, mind you in 1947, Melbourne was slightly different to what it is today. But it was just different. I mean, then, of course, we were in a different culture, different language, different customs, then different sort of food things. I mean, coffee in those days came in a bottle called turban coffee essence, and that sort of stuff. And then of course, my English was sort of minimal, but I picked it up. I mean, kids do. It's a different world. And you adapted.

LAURA THOMAS: What was school like for you?

GARRY FABIAN: I mean, the first year in secondary school, I mean, I wrote with English, but I had, so my, my writing, and that was a bit loose, which is ironic, saying, I finished up working forty years as a journalist.

LAURA THOMAS: Yes, you made it work for you in the end.

GARRY FABIAN: I mean, this is the point, when you go through that sort of thing, you somehow got a mechanism to adapt, because things keep changing.

LAURA THOMAS: And I'm curious to know, you've essentially grown up at this point that we're talking about, you've grown up with restrictions on you with your freedom completely suppressed, then you've travelled across the world, you've arrived in Australia, and the other children that you're in class with have not been through anything similar. I'm assuming.

GARRY FABIAN: The thing was that in 1947, mass migration was a bit of a novelty. There was no prejudice, there was just curiosity.

LAURA THOMAS: So were you asked a lot of questions about your experiences? Did you talk about your experiences?

GARRY FABIAN: I mean, the Holocaust, the Australian population was a totally unknown, it had no relevance to them.

LAURA THOMAS: Did you speak about it much at home as well, your experiences or was it now in the past?

GARRY FABIAN: That's a very good question. Because when I wrote my, my book back in 2002, I sort of asked my mother things and she says, 'Look, this is back there, we don't want to talk about it'. So and I've had the same experience. I mean, I've done some work with both Holocaust survivors. Done some writing for them and Vietnam veterans. And many of them just sort of pull down the curtain. Now, I mean, there's not many the Holocaust survivors, but the Vietnam vets are starting to open up because they know once they're gone, the true story will never be told. So no look, we didn't really, particularly as I said later in life, and I wanted to interview her mother on these things (she said) 'No, look, this is the past. We don't want to talk about it. Let's let's move on.'

LAURA THOMAS: Now, Gary went on to have a very successful career in various pursuits, including in journalism, but you have been back to Germany several times...

GARRY FABIAN: I've been back about, must be about eight times, in the last 40 years.

LAURA THOMAS: Were you hesitant to begin with?

GARRY FABIAN: Well, the first time I went back in '87, we went to Europe, went to sort of the France, went to other places went to Greece. And we did go back to Germany briefly. And look, I was somewhat hesitant because for the next two or three trips, whenever I saw on someone on the street in their 60s or 70s, my first question that came to mind, 'What on earth were you doing during the Nazi era?'. I went back to Theresienstadt a couple of times visiting. It was still under, behind the curtain. So we just spent the day there and did that. But the second time I went back, was in 2001, it was the strangest thing - they wouldn't stop you going anywhere. You could actually go a little in have a meal. And the other thing, when you ask, inevitably people will ask 'What sort of impression did it leave with you?'. Well, I mean, I'm a dog lover, and I was walking down the street, and the dogs barking behind me. In a spun round, I expected the see an SS man with an Alsatian. And the other thing was going into a little cafe or little inn and actually ordering food.

LAURA THOMAS: It's so far from your experience.

GARRY FABIAN: The other thing, there was another trip to Theresienstadt in 2003, which has relevance that in Stuttgart they established a memorial for all of the Jews in Stuttgart. There is a big memorial at the old railway station. And there's a foundation that sort of established this, they invited me and also a local television station, 'let's go make a documentary of this trip'. So there was two survivors. One, she actually lives in America, there was 20 Young people, there was some musicians, there were some all sorts of about 60 people went to Theresienstadt for a couple of days. Anyway, for some reason, I mean now, Theresienstadt, a lot of tourism goes there. But the two of us and my wife, there's accommodation, a lot of students accommodation, but they accommodated us in a town nearby. Now whether they thought that being in Theresienstadt overnight would be traumatic, or whether they felt the accommodation wasn't quite up to standard. Anyway, we went there by bus, we had dinner, then we were looking for the bus driver. And walking through the dark streets, look, I don't believe in some of these mystic stuff, but I had this feeling there's a lot of sort of souls there sort of talking to me, 'you must go and tell the story. We can't'. Look, It probably sounds totally ridiculous

LAURA THOMAS: It doesn't.

GARRY FABIAN: So these are some of the impressions. Then the next time we went back and this started really my journey of of telling the story. As I said, I was working as a journalist then and I was doing a lot of motoring writing, and I'd organised the trip. So it was a bit of a put together. Mercedes Benz, BMW, I got Lufthansa to give me half a ticket because we're doing some travel stuff. And I spent the day at Mercedes Benz in Stuttgart. But certain days, I didn't speak German. Anywhere, they were hospitable, they showed me to the design studio, showed me the plans, took me to the boardroom for lunch. And as I was leaving, and I sort of have this twisted sense of humour, I said to them in German 'Well thank you gentlemen, it was a most fascinating and enjoyable day'. Now I could see them 'What on earth were we talking about when he was...' Two of the older men looked very uncomfortable. I could see that they were obviously there during the war, they were probably involved in slave labour. Anyway, one of the younger ones came up and said 'Are you still in Stuttgart for a little while.' I said 'Yeah, I'm here for a couple of days'. He said 'Could you come to dinner with a group of friends of mine?'. So I went to dinner and I talked about the story. And that's where it actually dawned on me that it's so important to pass the story on. I mean, before that, I hadn't really considered it. Now the next trip to Germany, that was in 2001. Now, a lot of the German cities invited their former Jewish citizens back and I call it the German guilt trip.

LAURA THOMAS: Ah kind of an apology

GARRY FABIAN: Yeah, anyway, we're still had trepedations going because it was sort of... but in many ways, we met a lot of people. And then for some reason, maybe I didn't move back on a call for volunteers. I got picked to give the speech at the farewell dinner. And I more or less sort of said 'This has given us a different perspective. And given us a touch of what might have happened if history had gone the other way'. And that's really, I mean, to this day, they're still putting up monuments, they're having things. But the general population in Germany said, 'Look, let's move on'. And as I said, I've been there, eight or nine times. I speak to schools, I speak to community groups. And this happens almost constant, every time after, you know the formal thing, get together with a cup of coffee, and one or two kids will come up to me said, 'Look, we learned about this in school, but actually talking to someone who was there gives it a whole different sort of meaning'.

LAURA THOMAS: And Garry, you had an interesting interaction with a school child as well.

GARRY FABIAN: Yes. Well, at one of the school meetings, a young lad, must about 16, 17, probably 17, came up to me. I could see he was very hesitant. Anyway, we exchanged pleasantries. And they said, 'Look, I don't know how you're gonna react to this. But my grandfather was a guard at Auschwitz'. So I said 'look, that was your grandfather. This is you'. And then I did more sort of digging. Now, his grandfather was an 18 year old conscript. Now, I mean, I have this question, which I'll never find an answer. If I had been on the other side, how would I have reacted? Would I go along with it? Would I have stuck my neck out? I don't know. So look, the thing is that you're basically dealing with the third generation, and you've got to build bridges. I mean, hate does nothing for you. As I sort of said, when, in the book, one day, we may forgive but we must never forget. I mean sure, the right wing is rising in Germany, the right wing is fortunately small, but it's happening here. But you've got to get on with life.

LAURA THOMAS: And is this concept of ensuring younger generations remember, what's gone on in the past, is that why you continue to share your story?

GARRY FABIAN: Look, I think so. I mean, it's, I mean, I've made some very good friends over there over the years. So look, I think it's important, I mean that's why I', so involved with the Holocaust Museum, because let's face it, I mean, survivors are very, very fast diminishing sort of quantity, that I think it's important and when, you know, when I'm asked, so at the end of the talk, have you got any final words? Well, two words; never again. I think that really is the message. And I also have a message for the schools here, saying, asking a favour when we finish up to tell their friends and family who didn't come, what you've seen and encourage them to come. I think you've got to keep this connection rolling. I think the message, and even when I speak to schools at the Holocaust Museum, the message, it's in their hands that it never happens again.

LAURA THOMAS: Well, thank you so much, Garry, I think we all have a lot to learn from your story and your attitude. So thank you so much for sharing it with us today.

GARRY FABIAN: That's all right.

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks for listening to this episode of the Toys, Tales and Tenacity podcast series, and a special thanks to Garry Fabian for being so open in sharing his story.

This series accompanies the Toys, Tales and Tenacity exhibition, which is on display at the Shrine of Remembrance until August 2024.

The exhibition delves into the experiences of children during war, shedding light on their unique perspectives and the profound impact war has had on their upbringing. To learn more, head to the Shrine website – shrine.org.au

This was the first episode in a series of conversations about how conflict has impacted the childhoods of three different people. To hear the rest of the series, search Shrine of Remembrance wherever you get your podcasts.

Updated