- Conflict:

- East Timor (1999-2005, 2009)

- Service:

- Peacekeeping operations

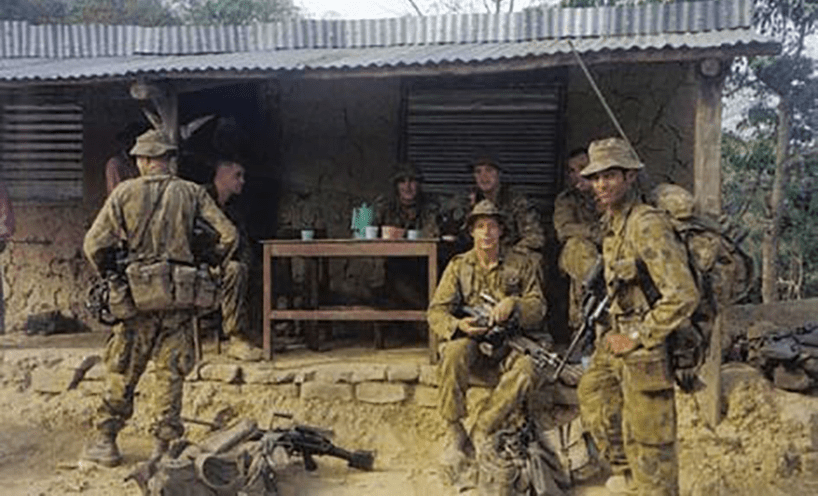

Australian Army peacekeepers, Shannon French, Tom Mahon, Tom Potter and Cameron Wheelehen had no experience and knowledge of the coffee industry before they stumbled upon the village of Belumhato, Timor-Leste in 2012. Their subsequent journey has been as much about helping the people of that beleaguered country as it has been about establishing their business, Wild Timor Coffee.

Private Shannon French learnt a hard lesson about Timor-Leste’s economy in September 2000, while on patrol with Charlie Company, 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR). Hacking a path through the scrub, French came face to face with an extremely angry man, armed with a very large machete:

He flew right at me. Under the rules of engagement, I could have shot him then and there, but I didn’t, and after a scuffle, managed to wrestle him to the ground. I thought he was a pro-Indonesian militiaman but when everyone had calmed down, we [the patrol] worked out he was an ordinary farmer. The weedy shrubs with the red cherries, that we’d been trampling for months, were his coffee plants.

Coffee is a very big deal in Timor and has been the island’s most valuable cash crop for almost two centuries. According to Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) figures, coffee generated 24 percent of the value of all exports for the country in 2017. It is grown by one-third of households and provides up to 90 percent of the annual income for one quarter of all Timorese.

French’s unwitting destruction of the precious resource was a potentially lethal provocation in a fledgling nation struggling to recover from a quarter- century of Indonesian rule and civil war. And French was finding Timor-Leste dangerous enough already:

People today don’t realise—it wasn’t peacekeeping, it was peace enforcement. There were dozens of hostile contacts. We’d come out on top but there were times when it could easily have gone the other way. A bunch of my mates were wounded, in any case.

It was frustrating, we didn’t know which villagers were pro-independence and who was pro-Indonesia. Whenever we examined the bodies of dead or captured militiamen, they were wearing TNI-issued [Indonesian Army] flak jackets, under civilian clothes.

We were on patrol for seven months, I didn’t sleep under a roof, or eat a hot meal in all that time. One day, an old woman in Tapo [Village] gave me a cup of coffee. I knew nothing about the stuff in those days—International Roast from a rations sachet, stirred with a stick, and I was happy—but it tasted like nectar and it is the only positive memory I have of that time.

When French returned for another tour of Timor in 2012—this time as a reservist with 5/6 Battalion, Royal Victorian Regiment (5/6 RVR)—he was heartened to find that a more optimistic and relaxed atmosphere prevailed. The acute threat posed by pro-Indonesia militiamen in 2000 was gone, and much rebuilding had occurred. Extreme poverty remained, however. It was on this tour, in company with three other diggers—Tom Mahon, Tom Potter, and Cameron Wheelehen—that French experienced his third transformative encounter with Timorese coffee.

The four peacekeepers met local boy, Jack, at Belumhato, nestled in the Aileu Forest south of Timor-Leste’s capital, Dili. Hard-nosed middlemen were gouging the village—their new friend explained— paying rock-bottom prices for coffee beans, they claimed were sub-standard, but which they then on-sold for big profits. Jack wanted to sell Belumhato’s coffee direct to Australia.

The diggers bought 600 kilograms of wholly organic beans (common plantation pests, khapra beetles and leaf rust diseases, are absent on Timor—rendering pesticides and chemical fumigation unnecessary) and transported them to Melbourne. The resulting brew was sampled by French’s neighbour, Tony Zammit. It was, according to the former coffee company national sales manager, ‘amazing’.

Coffee was introduced to Timor by the Portuguese two hundred years ago. Plantations, abandoned during decolonisation in the 1970s, fell into disuse during the 24 years of Indonesian rule. Feral coffee plants, spreading through the jungle, developed into a unique natural crossbreed of the arabica and robusta varieties—the hibrido de Timor.

Hibrido de Timor combines the sweet, smooth flavour profile of arabica with the coarser high caffeine-hit of robusta—blending, in the minds of many aficionados, the most compelling elements of each. The hybrid—unique, vigorous and complex—is an apt metaphor for the tiny, irrepressible, nation, which fought fiercely for its independence and now strives to establish itself on the world’s stage.

French and Potter returned to Belumhato in late 2012 when their tour ended. Watching youTube videos on the finer points of coffee production, the men had big plans to improve the lot of the Timorese (and themselves)—‘…through trade, not aid’. Potter, the group’s chief buyer for many years, plays a smaller role nowadays, but retains a silent stake in the wholesale importation business, Wild Timor Coffee, which today is run primarily by Wheelehen and Mahon.

The Wild Timor Coffee Co. supplies dozens of cafés, across Melbourne and Australia. Two of these cafés (in Carlton and Coburg) bear the Wild Timor Coffee name, as does a coffee cart business in Brisbane, owned by ex- 6RAR peacekeeper Luke Worth. Another former 6RAR man, Vietnam veteran Paul Beraldo, of Melbourne coffee industry big fish Beraldo Coffee, has become an important mentor for the business. He and French met marching to the Shrine of Remembrance on Anzac Day, 2001.

Along with a number of other commercial ventures, including a coconut oil business based in the village of Lospalos in Timor-Leste’s far east, French is responsible for Wild Timor Café on Sydney Road, Coburg. The young, enthusiastic staff who manage the café day-to-day are as passionate about social justice as they are about coffee culture. Staff forgo tips—the coins and notes thrown into the jar instead fund new equipment and development projects in Belumhato as well as staff exchanges between Melbourne and Timor. Mahon explains:

Hospitality in Timor falls into two extremes. There’s a few ex-pat owned businesses—cafés, bars, restaurants—that set the standard, but mostly its village Jo(e)s working out of huts, using rusty knives, wood fires, or whatever. We bring villagers to Australia and show them modern kitchens and catering techniques. We also supply the village with water tanks, coffee machines, etcetera.

Store manager, Lauren Harrison, loves being able to ‘…work and simultaneously help people.’ And Wheelehen understands the sacrifices they make:

We’ve sent staff to Timor over the years. They experience the culture and become as passionate about the place as we are. They tend to stick around a little longer and spread word about what we’re trying to achieve, here.

When asked why the peacekeepers embarked upon a business for which none had prior knowledge, Wheelehen replies:

Business, politics and development aside, we saw what was happening in Jack’s village and had the means to do something about it. Australia really owes a debt to the East Timorese. We invaded their country in 1942, which directly led to Japanese intervention. Australian commandos, fighting the Japanese on Timor, depended on Timorese help and those people paid dearly providing it. Then the Indonesians show up in 1975 and we leave them to it!

Wild Timor Coffee have an excellent product, no question, but they have had a difficult road, nonetheless. Timor- Leste’s coffee industry is a premium, organic producer, backed by Fairtrade, but poor national infrastructure and high labour costs (stemming from Timor- Leste’s use of the United States’ dollar), reduces global competitiveness. Coffee yields remain low, nationally, due to low capital investment and simple farming methods. As Shannon French opines, ‘…there is nothing easy or straightforward about doing business in Timor.’

Giving villagers their due, means lower profit margins for Wild Timor Coffee. Mahon:

We buy the beans in raw ‘parchment’ form. We used to truck the stuff to Dili where it was processed—cleaned, skin removed, etcetera—before the ‘green bean’ was shipped to Australia. Recently we bought the villagers a coffee huller, which means they can process and bag at Belumhato creating seasonal work for 25 people. The cost per bag will go from 25 to 50 cents per bag but we’ll wear it.

There is hope that these direct trade practices might pay off financially, though. Wheelehen again:

We’ve just become a certified social trader. The government’s talking about buying from companies that reinvest 50 percent of their profits into improving poor people’s lives. We’re doing that already employing villagers and running at a loss most of the time [laughs]. We [are] now waiting for the big contract for the Royal Children’s Hospital… [more laughter]

When asked why Wild Timor Coffee persists working with the Timorese when they could arguably run a more profitable business dealing in another nation, or by employing a more hard-nosed attitude, the last word goes to Mahon:

We have a business we are proud of and we don’t have to work for some sucker. Every year we can visit our mates in Timor and escape the Melbourne winter—which is coffee season. When we were peacekeepers, we were told ‘if you see a broken-down car, leave it—this country needs to learn to stand on its own feet’. Now if we want to build a water tank in a village—we build a water tank. Need a school? Let’s build a school. Give the village a new hulling machine? S--t yeah! Let’s do that too. It doesn’t always work— sometimes we f--k up—but nothing ventured, nothing gained.

About the author

Neil Sharkey has been the Curator at the Shrine of Remembrance since January 2007. He curated the Shrine’s Second World War Gallery and has developed dozens of temporary exhibitions including, most recently, The Korean War and The Cinderella Service: Australians in Coastal Command 1939–45

Updated