Take a peek behind the curtain of the Between Two Worlds exhibition with veteran artists Ben Pullin and Sean Burton.

In this podcast, Ben and Sean discuss their service and how it inspired their art. They look back at how the exhibition came to be and the response they've had from friends, family and visitors.

Sean and Ben also unpack the story behind a piece of art on display.

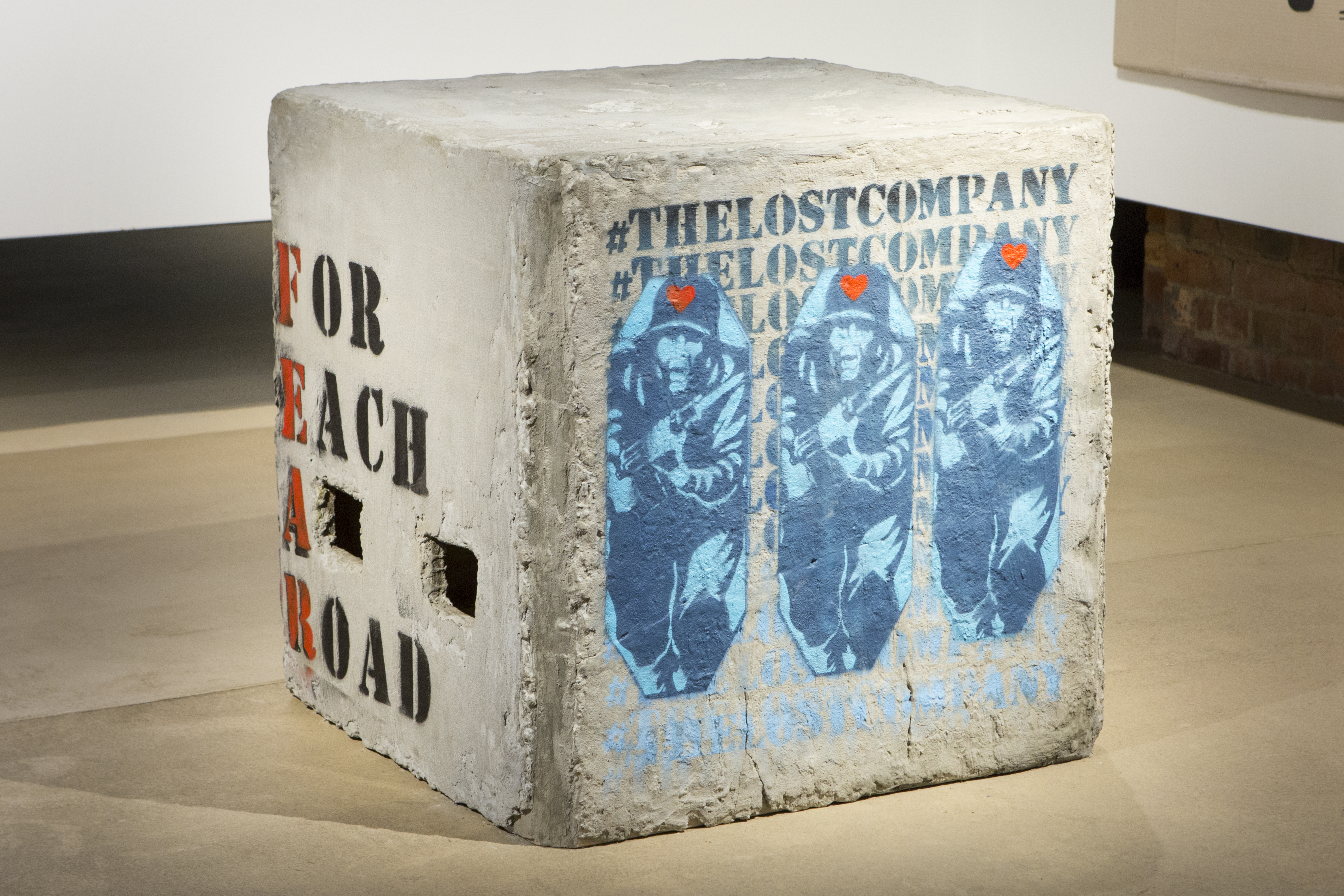

Sean references The Lost Company (2018) as seen below.

Ben discusses his painting, Displaced (2019).

For more information about the Between Two Worlds exhibition, click here.

Learn more about Sean Burton here.

Learn more about Ben Pullin here.

Learn more about Rory Cushnahan here.

Credits

Music: 'Our Bar' by Sam Barsh

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: Hello and welcome to the Shrine of Remembrance podcast, where we explore all aspects of military history.

My name is Laura Thomas, and I’m the production coordinator here at the Shrine…

The Shrine of Remembrance acknowledges the Bunurong (bun-ah-wrong) people of the Kulin (cool-in) Nation as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we honour Australian service men and women; and we pay our respects to Elders, past, present and emerging.

On this episode of the podcast, we’re looking into what happens when art and service collide…

If you’ve been at the Shrine recently, you may have seen our exhibition ‘Between Two Worlds’, featuring veteran artists Ben Pullin, Sean Burton and Rory Cushnahan…

Across painting, sculpture and street art, each artist takes a deep dive into themes like identity, dislocation and resilience.

It was a bit of a bumpy journey getting Between Two Worlds up and running with COVID lockdowns wreaking havoc, but we’re now nearing the final weeks of the exhibition…

So today I’m sitting down today with two of our artists to reflect on the past few years with a peek behind the curtain of how Between Two Worlds came to be…

Ben Pullin and Sean Burton, hello and welcome!

BEN PULLIN: Hello, Laura.

SEAN BURTON: Hi, Laura.

LAURA THOMAS: And Ben, we do have another special guests with us today. Do you want to introduce him?

BEN PULLIN: Yes, I've got my assistance dog Shiloh here. He's going to be hanging out.

LAURA THOMAS: So if you hear any shuffling, scuffling about that's Shiloh.

BEN PULLIN: Yep that's him, yeah.

LAURA THOMAS: So I thought we'd start by talking a little bit about yourselves. So, Ben, Sean, do you want to introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about you and where you served?

BEN PULLIN: Yep. Okay. I joined the Army way back in '91. I served with the 2/4 Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment in Townsville, and I served overseas, in Rwanda for a deployment there. And later on in my career, I also served in East Timor.

SEAN BURTON: I'm originally from the UK, I first served in the British Army as a young man, served as an infantryman. And in my search for sunshine brought me out to Australia. And I couldn't believe what I'd found, it was really a land of milk and honey and absolute paradise. And I did everything I could to stay. And part of that was to enlist as an Australian soldier. So I joined up and I too served with the 2/4 Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment, second to none. And I also served later on with the Fourth Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment, and I saw deployments to East Timor, the Solomon Islands and the Middle East.

LAURA THOMAS: So did you two meet during your service then?

BEN PULLIN: Uh, yeah, we both served in the same platoon in the RAR, in the 2/4 Battalion. Sean was one of my platoon staff. And I was a young digger

LAURA THOMAS: What was that like?

BEN PULLIN: Oh yeah, I think, back then, Infantry Battalion was very traditional orientated unit. So yeah, I think anyone who's served back in the early '90s in the regimen probably had a fairly unique experience of service.

SEAN BURTON: Yeah. And I think it really was a time, it was a time of great change. Because around that time, we'd gone from accommodation where it was eight man rooms, you'd share the room with seven other guys, or you go to a four man room. And at the time, when I met Ben, which was in the early 90s, Ben had just joined up, when they'd actually said, 'Well, we should start giving the guys coming through single rooms, like what they'd expect at home'. And I remember when I first met Ben, I was one of the platoon staff and young Ben Pullin had marched in and introduced himself. And one of the first things he asked me was when he was going to get the internet connected to his room, which was absolutely mind blowing. And I remember saying to him 'The inter-what?' you know, but that was the expectation. Ben was of the new generation coming through. He was the first digital soldier I met. And there was this expectation that, yeah, okay, we want things like the internet. And yeah, that was quite a revelation. I remember it sort of stunned me when I met him. And he sort of said, 'Okay, when am I getting the Internet to my room?' And I was like, 'Dude, you're lucky that you're even getting a room. Most of us have had eight man rooms for man rooms, and you're getting a single room to yourself, and you want the internet?'. So yeah, that was a time of great change.

LAURA THOMAS: Ben, did you ever get the internet?

BEN PULLIN: No, not there, not for a while. I did manage to score the title of being the computer geek for the battalion. So I was absconded to fix and do things on computers for most of my time there. But unfortunately didn't quite manage to swing a phone connection, it was dial up back in those days. So that's what I needed.

LAURA THOMAS: And so you met during service. But how did you reconnect after that?

SEAN BURTON: Well, I think we went our separate ways. Ben deployed to Rwanda. And just at that time, I decided I wanted to go overseas. I left the army and went and did security work overseas. And that's where we sort of parted. And it wasn't until nearly 20 odd years later, we just had a random coincidental bump into each other at a music festival and, you know, Ben emerged out of the crowd and just suddenly, 'Gee, I know you! haven't seen you for like, 20 years', and he was like, 'Dude, what do you been up to?' And we had a brief chat and 'Hey, I'll catch you later. See you soon' and went our separate ways. And then a couple of weeks later, you came around my place and we sat down and discovered that we'd really been on our own path, creating art, doing our own thing, and that was quite a revelation. And it's funny, you know, I always say this now, when you bump into people who you haven't served with for a long, long time, it's just one of these things, you just take off really from the last time that you saw them. And relationships, you just take off bang, and the same bad jokes, the same nicknames, the same memories, same shared history, you just take off straightaway. There's no awkwardness. I think you know each other, you've seen each other at the best and the worst. And, yeah, and it was pretty easy. We just sort of got going straightaway.

LAURA THOMAS: And Sean, you mentioned that you were both kind of on separate journeys with your art. I'm interested to know kind of what came first for you? Was it art or service, or was there kind of a collision of worlds,

SEAN BURTON: I had always been interested in art as a kid in graphics, more so. And then, you know, being a young teenager, I got into graffiti. And that sort of all came to a crashing halt when I decided to enlist as a young man. But then it sort of took off again after I'd left the military. There was just that gap, had that creative gap. And yeah, I just was drawn back to art again, as a way of expressing what was going on. And as they say, you know, a picture says 1000 words. And I really found art was a crutch to lean on, it was something for me to use to just really express what was going on, at the time in my life, a time of transition leaving the military. And I needed to really communicate what was going on. And I couldn't do it verbally, but I found that I was just drawn to doing it through art.

LAURA THOMAS: And was it a similar situation for you, Ben?

BEN PULLIN: I definitely was practising art prior to joining the military. Not so much, I really didn't have time too much for it during my service. Probably towards the end of my service, I did start to practice more art as a bit of an escape from the everyday sort of grind of military life.

LAURA THOMAS: And we are in a very audio driven medium here. But Ben, do you mind describing kind of your art style? For someone who's never seen it before, how would you describe it?

BEN PULLIN: Yeah, there's fairly abstract concepts in my practice doing sculpture. A lot of my materials are from objects that I've found or collected and repurposed. And a lot of it is metal, different types of metal that I've put together. So yeah, it's kind of figurative work, sort of portraiture pieces, but with more abstract kind of shapes that represent figures and things like that.

LAURA THOMAS: And Sean, you spoke a little bit about this, but it's kind of in the graffiti realm of art, can you kind of describe what your work is visually about?

SEAN BURTON: It's probably easily described as stencil art. So my primary, my tools are usually aerosol paint and stencils. So whether they're paper stencils, or acetate plastic stencils, multi layered. And I try to keep it in a simple form, that it can be applied on the street, or it can be applied on the canvas. And I suppose I do it on the street, because I mean, like most artists, you want your art to be noticed. You want it to be seen. So I'll take it out on the street. And that's what I enjoy doing. So maybe that's the genesis of it. If you think of street art, it's a form of street art,

LAURA THOMAS: Ben did you ever think that you were going to go from you know, making art at home and in the studio to having it on display?

BEN PULLIN: Oh, yeah, absolutely. No, I mean, I've always, the art that I've done, I'm quietly confident in what I've been doing that, you know, and I've sort of ventured in and talked to people about, you know, probably, you know, nearly 20 years ago now, about having exhibitions and, and getting in the art space. But yeah, just never been sort of in a position to do that. So, yeah, a few sort of things fell together. And that's where we've sort of ended up having that kind of opportunity given to us.

SEAN BURTON: I actually had no idea that any of my work would end up in an exhibition. I really wasn't even thinking that. I was quite happy with it just going out, doing it in public places, doing our streets, alleyways, whatever, laneways, and it really was just not even considered. That changed when we finally met people who were in the art therapy space, veteran art therapy space, who just said, 'Well, why not? Have you ever actually thought about it? You should bring the outside bring it in'. And yeah, that was the big revelation for me. I thought 'Okay, well, alright, why not? Let's give it a go. And let's give it a crack. Let's see how we go'.

LAURA THOMAS: And this is very new territory for the Shrine as well. It's the first contemporary art exhibition the Shrine has done. So how did you feel Ben when you saw your art installed and hanging on the walls, and there in sculpture form as well?

BEN PULLIN: Oh yeah it's great, it's a great experience to be able to see that there. But more so too, I think it's more, it's not so much seeing it there, but if there's a piece of art that you truly believe in or are happy with, to be able to share that with other people is, is more of the reward, it's not so much that it's there on the wall, or on a wall somewhere. The proof is in the pudding as in, if people enjoy that, and the feedback that you get from it, and people generally did, they wouldn't be there if they didn't, if they didn't find it pleasing in some way. So yeah, that's, that's kind of recognition. And it's great to see people enjoying art in general. So if you can be part of that, it's a great experience really.

LAURA THOMAS: How about you, Sean?

SEAN BURTON: I personally really enjoyed the opportunity to tell the stories of the people we've painted. And the feedback I get from those people who are still alive that we've painted, that is just gold for me.

LAURA THOMAS: And Sean, a lot of the people that you've painted, and in your art are real people, they're not fictional characters, they're people who've sat for you. Have any of them come to the Shrine and seen themselves on display?

SEAN BURTON: Yes, they have. And for me, that is one of the most satisfying parts of this exhibition, is to invite our sitters, as we call them, people who sat for me, to come in and to see the fruits of my labour, you know, and they bring their families in. And it's, it's emotional. And they are, I think they are very proud. Honoured that they're part of the Shrine collection. And, for me, that's one of the big kicks I get out of my work. For me, it's the unveil, when you show your subject their portrait, they haven't seen it. That's the way I normally work, because I take photos of them, we go away, there might be a little bit of consultation about a few minor things, minor details, but then they won't see the artwork until we do the unveil. And I've always said that, to me, that is what it's all about - that moment that you drop the cloth and the portrait is unveiled to them, the reveal, and just the look on their faces. I don't look at the portrait, I'm watching their faces when you drop the cloth, because to me, that's gold. That's the moment and the moment of realisation and the big smile that usually cracks across the face. But then to bring it into the Shrine. And that's been really good.

LAURA THOMAS: Before we came into record today, I asked both of you to choose one of your pieces that's on display, and talk about it in a little bit more detail. Like I would love to talk about them all, but we obviously don't have enough time for that. Sean, what did you choose from the exhibition?

SEAN BURTON: Well, I chose my piece of work called the Lost Company, which is a replica traffic bollard. Just a bit of a backstory with these, back in 2017 in response to the Bourke Street attacks, there were 200 of these solid concrete blocks put around the CBD to keep cars off pavements and keep our pedestrians safe. And once they were put in, you know, you really saw them as blank canvases in the middle of the city. Cubes with four sides, blank canvases. And so at the time, I wanted to start a campaign, a social media campaign, to raise the awareness of the high rate of veteran suicide. And so we went out and started painting on the side of these, these traffic bollards strategically placed around the city. And yeah, they got a fair bit of traction. And yeah, there was a hashtag on all of the blocks, which was the Lost Company - it got traction, got people talking. And there's still some of them scattered around the city now. I mean, what's that five years, there's still some. And it was only recently, Ben and I were actually on our way here. And we walked along a laneway. And we saw one that was actually put up in the Lost Company stencil that we used on the on the blocks was still up there from 2017. And good on the people who, whose wall it was because they had actually buffed everything around the Lost Company logo, put pipes over the top of it, and left it there. And so it was that was that was quite a good thing to see that recently. But yeah, they weighed nearly 1000, what did we reckon Ben? Nealy a tonne, a tonne of weight. So we made a replica one at our studio in Footscray. It was made by a friend of ours, Tom Scott, who's a fantastic furniture maker, he made the wooden box for us. And then we got cement, rendered it and added some of my artwork to it to really, you know, authenticate and just give it the feel of what it was out there on the street. So yeah, so it went from being nearly a tonne to just about 50 kilos. And we originally pitched it to the Shrine that we wanted to actually bring in one of the real concrete bollards. But obviously logistically bring, you know, this huge lump of concrete a tonne into the Shrine, it was probably not going to do the lovely floors here any good. And it was a logistical nightmare. So that's why we went with a replica. But yeah, that's, that's something we like. And we're actually going to, when it leaves the Shrine at the end of July, we've got plans for it to go on to other exhibitions as well.

LAURA THOMAS: Brilliant. Can you talk me through some of the art that's displayed on the side of it as well?

SEAN BURTON: Yes. Now on one side, there's a little dog having a pee. And that was a really simple little stencil. But that's been scattered throughout inner-west Melbourne. Usually on street corners, there's still plenty of them around. They're all down at street level. On another side are the letters fear F-E-A-R, and that makes up the word 'For Each A Road'. And again, that was a piece of music I'd heard a long time ago by a guy called Ian Brown, who was the frontman of a band called The Stone Roses. And it was just a fantastic piece of music that I really loved. And I just liked the way that it worked - For Each A Road. We all have our own path. We're all on our own journey. And I like the fact that sitting on a bollard, maybe obstructing our journey, maybe obstructing our path, maybe an obstacle to be gone round gone over. It just fitted in nicely with it. And you know, these ugly squat blocks in the middle of people's paths. It was just about me just wanting to put a bit of me on that block.

LAURA THOMAS: What's it like having - your art traditionally is out on the street, so it's not permanent. What's it like then having that brought into a very permanent kind of exhibition?

SEAN BURTON: It feels quite sterile. Yeah, it's very strange. So what I try and do that everything that I will paint on a canvas, I will also try and replicate out on a street. So it's like a street gallery if you want to call it that. So yeah, it's nice. It feels like it's very sanitised when it's brought in here, but I realise, you know, hey, that's what it is. You know, how lucky am I to have my artwork on display here? So I'm not knocking it, but I'm just saying it's a very different medium and has a very different feel. And it feels quite clean, quite clinical. Whereas out on the street, it's weathered, and you know, whether it stays there, it's quite ephemeral. It could be gone, it's tagged over, it's buffed over. It's, you know, it's exposed to the environment. But then you can see I think when you look at the artwork in there of Babs which I mean, we've spoken about this before, that was a piece of street art that had been exposed to the elements for over a year. And it had become quite weathered, and it was deteriorated. Again, that was one time Ben and I were just walking through a city just checking out the street art scene, what was going on, what was new, what was fresh, spaces, potential for us to put some artwork up there and we did see Babs' portrait still on the wall. But the taggers were working their way up the street and we thought it wouldn't be long before he was going to become just another layer of someone else's street art. And that's when we decided to take him off the wall because he had taken on a life of his own. All the deterioration and as he had been exposed to the elements had given him wrinkles, and almost three-dimensional wrinkles that you could actually see all the layers of other people's street art underneath. So maybe that'll give you an idea when you can actually see when you look at some of the artwork, you can see the canvas versions. And then you can actually see, well, this is what it would look like if it was actually on the street, how weathered and deteriorated it is. So yeah, I like that there's a nice, you can actually look, especially in here where you've got them, some of the artworks nicely framed and it's on canvas. And then you can look at something like Babs which has been taken off the street, and framed and preserved. And you can see, well, this is the weathering process. This is what it would look like if it was actually out on the street.

LAURA THOMAS: And Ben, you also chose something from the exhibition to talk about. What was that?

BEN PULLIN: I chose a painting based on a scene in Rwanda. It depicts a soldier providing a security patrol in Kibeho, late 1994, and greeting some children and other people around the camps as a smiley face, kind of.

LAURA THOMAS: And the painting is based off a photograph?

BEN PULLIN: Yeah, it's based off a photograph that I have taken by a mate, Mick Craig. So he took a photograph of me during one of those patrols. And yeah, so that's, that's kind of loosely where that painting was based

LAURA THOMAS: Something that really strikes me about the painting is the colours that you used. There's a lot of dark kind of reds and oranges and blacks, is there a reason why you chose those colours in particular?

BEN PULLIN: Yeah, it's a palette I'm comfortable with that I've sort of gravitated towards using as an Indigenous Australian, and also from my service. I think it's a palette that's probably familiar to many people in services, especially infantry type guys, you know, spent a lot of time digging in mud and being covered in it. And in Australia, we're surrounded by the red dirt, and those kinds of ochres and, and those colours. So that's, that's the palette that I pretty much stick to nowadays.

LAURA THOMAS: And it's quite a large piece. How do you actually practically go about the process of making a piece so big?

BEN PULLIN: There's a lot of planning that goes into it. There are smaller sketches and, and trying to try to figure out proportions and, and what works. Because it's really a one shot, kind of wonder with working on a white canvas like that. So once you sort of committed to the piece, that's you, it either works or not, it doesn't and if you stuff it up, you can't really unlike using sort of a lot of background paints and infills and stuff, you've pretty much trashed the canvas and start again. I guess the point is, I work fairly quickly on some of these pieces once the final work has sort of been settled on. And then it's being more, I'm not a photo realistic painter. It's more the conveying the idea of the shapes and, and such, rather than trying to get the minute detail of an eyebrow or something. So it's, it lends itself a bit to flowing and freely onto the canvas.

LAURA THOMAS: How long would a piece like that take you?

BEN PULLIN: Eight hours?

LAURA THOMAS: Oh, really? Wow.

BEN PULLIN: Yeah. So from the from actually putting it and committing it to Canvas, yeah, it's, it's actually quite - and having been an oil painter in the past, it's those kinds of Burnt Umber and Raw Sienna shading is some of the first coats that you put onto a canvas if you want to do oil paints which are translucent. So one technique is to paint the shades and tones first, and then add colour over the top to bring a painting to a full sort of colour image, but it's kind of like stopping after after the first stages.

LAURA THOMAS: Right, that's so interesting. What do you hope that people get from this painting? What's the message that you wanted to convey through it, if any?

BEN PULLIN: There's a lot of different messages from our service in Rwanda. But this piece is, kind of conveys a sense of hope and, and well being and goodness that was provided by a lot of Australian servicemen and women during the deployment. And there's a little sub story there of loss and a sense of loss, I guess, from the sort of ghost figure on the right hand side of the painting which depicts, you know, there was certainly a lot of unknown and events and people that sort of disappeared during our time there that, you know, obviously weren't part of our contingent, but local Rwandan Rwandese that obviously would not, would not make it through, you know, our deployment there. Yeah.

LAURA THOMAS: And I'm curious, you've mentioned this, Sean, that this exhibition kind of existed right in the middle of lockdown. So it was a bit of a nightmare, getting it up and running with things closing and not actually being able to open it. But since you have been open, what kind of responses have you got from the general public or people that aren't in the exhibition? Has anything surprised you?

SEAN BURTON: Me personally, I find it, I've had a few funny times when I've just been at the exhibition either just going to check it out, or I'm meeting someone there, and we we're talking, we're meeting people there. When people actually recognise me in one of the portraits. I'm in a cameo in one of the pieces, the Untitled piece, you know, there's no signage that it's me, but I just find that I'm just that makes me laugh when people go, 'Hey, that guy in the picture, he looks just like you. Do you know tha?'. And I go 'Yeah, so he does', and I don't say who it is, it's me. But I've enjoyed that a couple of times, that's happened. One of the other things I've enjoyed, when I've been in the exhibition is just overhearing snippets of conversations, people talking about pieces of equipment, talking about times that they served, and the memories that the artwork has invoked in them. And you know, it's nice, it's being anonymous. And when you look around, and you can see, this is, I'm part of this body of work, people don't realise you are one of the artists and to actually hear people talking about your work, and just overhearing whether they think it's a load of rubbish, or they think, 'Hey, I've really liked that'. So that's, that's been interesting. Just being anonymous, sometimes in the crowd, if there's a crowd in there looking at it, and you're just standing at the back, just overhearing conversations, hearing what people pick up on.

LAURA THOMAS: We're speaking now in June 2022. So there is a few more weeks left on the exhibition. But Ben, for those who haven't seen it, what do you hope they take away from Between Two Worlds?

BEN PULLIN: I guess I just hope that anyone who hasn't seen the exhibition maybe comes and checks it out, and perhaps reads some of the stories behind what the art is about. So not so much about appreciating it as fine art or contemporary art, so much as the stories behind the art and how they relate to the art itself. So that's probably the biggest, the biggest takeaway from it. Not so much as an art critic on the techniques and the how magnificent it is, but rather just the stories behind it, and appreciation of stories told by other veterans in their art.

LAURA THOMAS: Sean, do you have a response for that as well? What you hope people who haven't seen the exhibition will get out of it, or what you hope the message they take away is?

SEAN BURTON: What I hope people take away from it is that they can see a bit of their story in some of the artwork that we've got up there. And it is a optimistic exhibition of our stories. It's a story of resilience. And it's a story that I mean for the three artists ourselves, that this has been no easy task. It hasn't been a flash in the pan, an overnight thing. We've worked hard at it and we're very proud of it. But I really want people who do visit the exhibition, just to look into the stories of the people that we've painted. And I just think you cannot help but smile when you're down there. And I encourage everyone to look for the secret piece of street art that is hidden in there.

LAURA THOMAS: All to be revealed when you come and visit in person at the Shrine. Now the exhibition itself will live on on the Shrine of Remembrance website, we've digitised it so you'll be able to virtually walk through. But for those wanting to follow your art and where you go in the future, how can they do that?

SEAN BURTON: For any future announcements about some work, exhibitions, shows featuring Ben and I's work, you can check out my Instagram which is SB six, six. That's S B, the numeral six, and the word S-I-X. SB six, six.

And we will definitely be watching that space, but thank you so much Ben and Sean for coming in today and having a chat.

BEN PULLIN: No worries

SEAN BURTON: Thank you very much

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks for listening to this episode of the podcast.

Between Two Worlds is on display at the Shrine until the end of July 2022.

If you want to hear more about Sean and Ben, or meet one of the other artists in the exhibition, Rory Cushnahan, head to the Shrine of Remembrance YouTube channel and search ‘Meet the artist’.

As I also mentioned in the podcast, this exhibition has been digitised and will be available on the Shrine of Remembrance website soon, so keep an eye out for that one.

Until next time, thanks for listening.

Updated